Superman, the State, and War

Varieties of influence operations through popular culture

One of the most notorious international relations scholarly articles of all time is Alexander Wendt and Bud Duvall’s “Sovereignty and the UFO”. Wendt and Duvall argued that one could better understand the ontological foundations of modern political systems by addressing how states treat Unidentified Flying Objects (UFOs). They wrote

neither the scientific community nor states have made serious efforts to identify them, the vast majority [of UFO incidents] remaining completely uninvestigated. The science of UFOs is minuscule and deeply marginalized. … With almost no meaningful variation, states—all 190+ of them—have been notably uninterested as well. … For both science and the state, it seems, the UFO is not an “object” at all, but a non-object, something not just unidentified but unseen and thus ignored.

Disbelief in UFOs, Wendt and Duvall continued, was an affirmative requirement for modern political elites, because the existence of superior technological civilizations would shake the foundations of modern sovereignty (particularly its anthropocentric assumptions) to the core. Thus, elites cannot believe in UFOs: “We are not saying the authorities are hiding The Truth about UFOs, much less that it is ET. We are saying they cannot ask the question.” The stigmatization of UFOs as crazy/kooky, in other words, is not a scientific but a social phenomenon—a defense mechanism for those who constitute the state.

This hypothesis has attracted a share of scorn—it’s one of the sorts of articles that you learn about in whispers. With only 141 citations on Google Scholar, its infamy far exceeds its official impact (somewhat ironically). And the hypothesis has fared poorly. We know now that elites care deeply about UFOs and that UFO investigation is contested—that folks like (according to news reports) Senator Harry Reid of Nevada pushed hard for more UFO investigations. So the deep account of social life that Wendt and Duvall offered is, well, an example of a falsifiable constructivist hypothesis.

Instead, I think we can offer an alternative account: the state is deeply jealous of other powerful entities and seeks to guard itself against any challenge. The agencies tasked with investigating UFOs in the United States have been Project Blue Book (in the U.S. Air Force) and other Defense Department agencies, not NASA or (recently) the FBI (X-Files to the side). Indeed, popular culture is replete with accounts in which the state recognizes and deals with aliens and other supernatural phenomena as entities to be transacted with and opposed. This, I think, is a superior account of how the state would respond to a challenge from superpowered individuals or civilizations: by mobilizing its resources to contain knowledge of the challenge to prevent panic and depression while also using such knowledge for its own ends.

I’m thinking about this because I have just finished Superheroes, Movies, and the State: How the US Government Shapes Cinematic Universes, a study by Tricia Jenkins and Tom Secker about official interactions with Hollywood productions. The book is a detailed and useful guide to the nitty-gritty of something a lot of us already knew: that the U.S. government leverages access to Pentagon resources, like bases, equipment, and personnel, to shape how the military is portrayed in Hollywood production. Access to such resources can save millions or tens of millions of dollars for a big-budget production, but producers who want such access need to submit to script review and consultations with the DoD in order to be granted access.

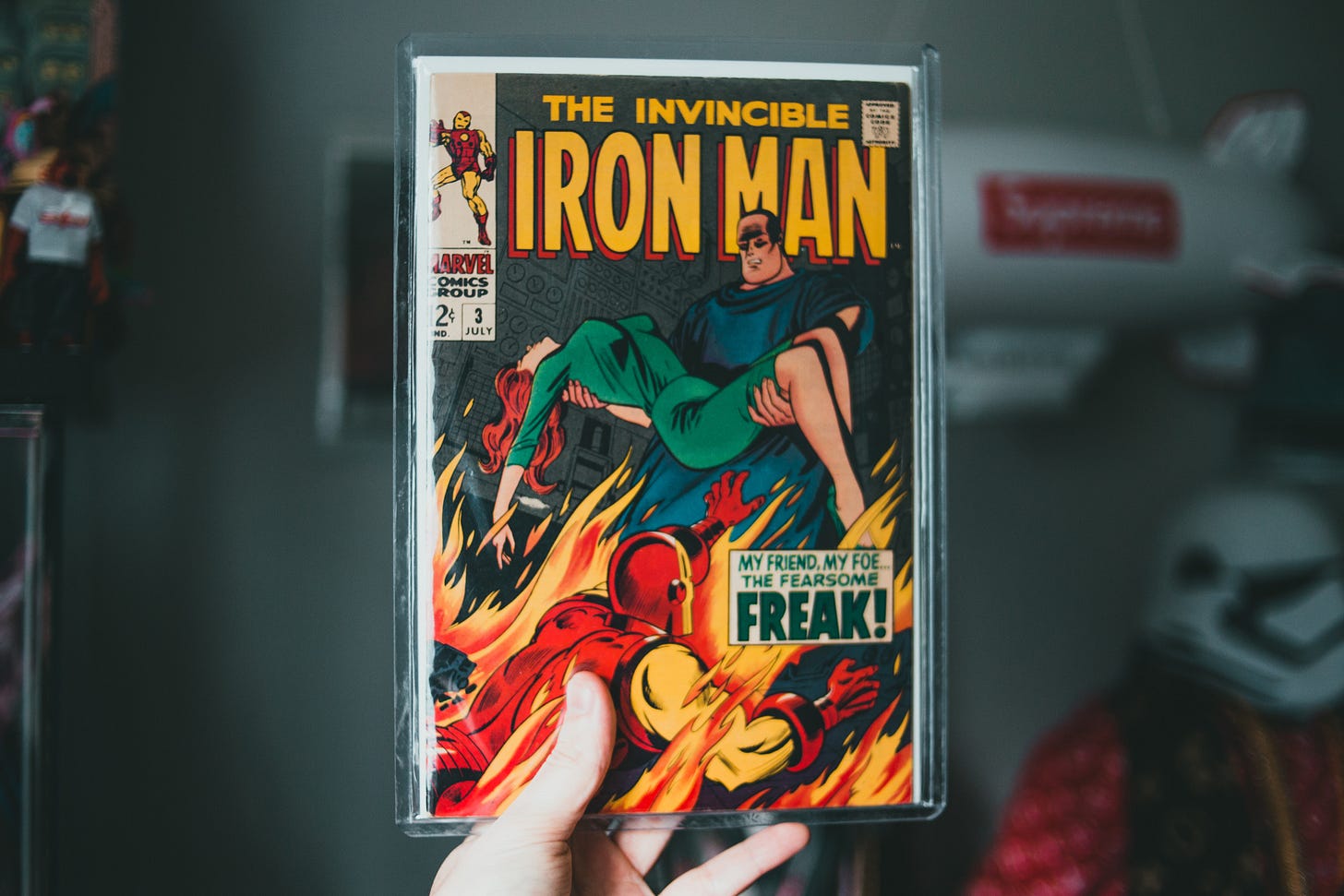

At times, these consultations can be extensive. Jenkins and Secker document how different takes on the Hulk were made more pro-military by the availability of military access, with many scenes rewritten or revised down to the dialogue level in order to portray the military as more competent, less bloodthirsty, and more interested in protecting civilians than first drafts. Early MCU films like Iron Man similarly took a softer line on the military and the military-industrial complex in general because they also received partnerships with the military.

Yet this was broken for a while with the release of The Avengers, a film that the U.S. government objected to because it showed an unaccountable international agency, the World Security Council, as authorizing—and launching—a nuclear strike on New York City. This posed a threat to the U.S. government. It’s okay to show that the military couldn’t handle a Thanos-backed invasion—but it’s a threat to suggest that the U.S. government would allow a world body to nuke Manhattan.

Such defensiveness extends even further into politics. When Black Panther revealed that the scientifically advanced Black country of Wakanda essentially had a cloaking shield hiding it from the world, Jenkins and Secker report, a U.S. intelligence agency posted that the U.S. intelligence community wouldn’t have been fooled by an invisibility cloak—that its use of national technical means would have led to the discovery of Wakanda. There is, as the kids say, a lot going on there, but for our purposes I think its’s evidence that the U.S. government is at least reflexively hostile to even fictional limits on its powers.

Tellingly, this locus of securitization is limited. NASA, which doesn’t really have a national security role, doesn’t vet films in the same way—if you’re interested in working with them, NASA’s (much smaller) Hollywood liaison office will support your project rather than asking for rewrites. The government-adjacent National Academy of Science’s Science and Entertainment Exchange can’t offer any assets of its own, but it will facilitate connections between filmmakers and experts to make the science presented in movies more realistic and creative. DoD, by contrast, sees its engagement with the movie and television industry as an extension of its security role—and as a consequence, U.S. politico-military interests will be protected even against fictional threats.

Where does this leave us? Instead of states that are intentionally unable to perceive threats (and opportunities) from exchanges with more advanced and powerful forms of beings, we have an account in which states are so sensitive to the ontological threat of power that they seek to preempt it using whatever means they have at their disposal—including, as in Man of Steel, portraying the U.S. Air Force as leading suicide missions against Kryptonian invaders to assist Superman in defeating the invasion. It’s okay to lose as long as you’re carrying out the roles that we expect of the state. In the same way, we now know that bureaucracies continued to investigate and document UFO (now known as UAP) activity in order to assess capabilities and intentions—just like an ideal Weberian state.