I’m Paul Musgrave, a political scientist and writer. This is Systematic Hatreds, my newsletter about politics and the study of politics. The newsletter takes its title from a line in The Education of Henry Adams:

Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, had always been the systematic organization of hatreds.

This week, we’re talking about teaching politics to the post-legacy media generation.

What the Kids Are Reading

When I was young in the provinces, a while ago, the News came from a handful of sources: local newspapers, television, and radio; the broadcast networks; newsmagazines; and CNN. In middle and high school, it was easy to be au courant with middlebrow news: if you watched the nightly news broadcasts and read Time, or even US News, you were keeping up pretty well. Higher-class types listened to NPR, watched PBS, and read major national newspapers (the Wall Street Journal had good circulation, but it was an occasion when the New York Times started Sunday service). Lower-class types … well, they still got the news, but radio played a much bigger role, relative to other sources.

It should be no surprise that this era has vanished. We all more or less take that for granted. In the 1990s, even well into the 2000s, the question of who would be a national news anchor was the subject of major discussion; nowadays, I couldn’t name any of the big three’s anchors. The Times is now a global brand, and the Post dominant nationally in a way that it never was before, but your local newspaper probably has about a third (or fewer) of the newsroom employees it had in the 1990s, if it still exists.

If you’re a typical adult, the story stops there. Things changed, and you changed with them. But at the top and bottom of the age distribution, things are different. For old adults, things never changed. For young adults, things were never the same.

And if you’re a professor, you have to exist in both worlds.

The idea that today’s college students are digital natives who can seamlessly navigate the online world is, well, doubtful. But even more dubious is the unthinking presumption a lot of faculty and institutions fall into of assuming that they were familiar with the now-vanished world of three broadcast networks and Time magazine.

The students are fluent in a different world that has nothing to do with the world that we olds were inducted into, and little to do with the digital world that we middle-olds inhabit. And it’s an open question about what world we should be helping students join—or whether we even know much about their world to begin with.

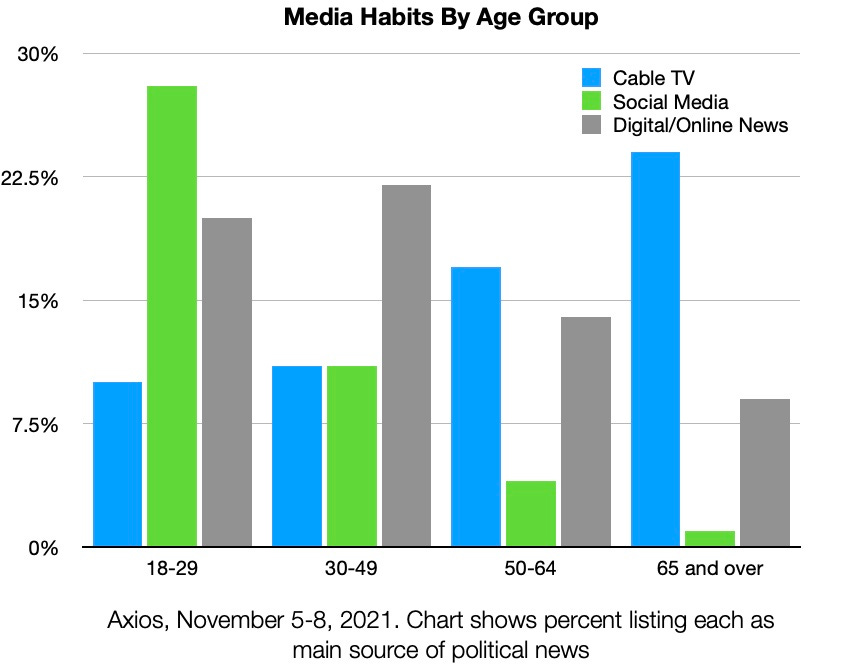

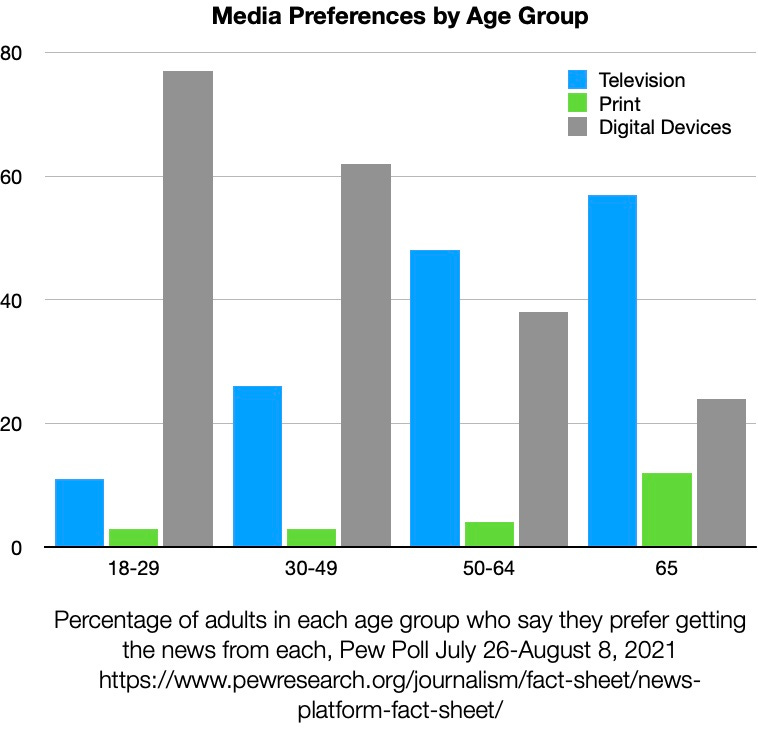

When I say the generations live in different worlds, I mean it seriously. Here’s a pair of graphs from recent polls showing two ways of measuring preferences for news sources by generation. Senior citizens live in a world of cable television and even print. Middles live in a world of transition. Yutes live in a post-TV, post-print world of digital sources.

I’ve told this story before, but it sticks with me. A few years ago, I was asked to give a talk about political communication to a group of senior citizens. The biggest reaction I got was when I mentioned offhand that I don’t subscribe to any print newspapers (still don’t!). I might as well have confessed to killing Natalie Wood.

“But how do you get news?” one asked. “I…have an iPhone?” I replied.

And it’s not like I’m alone. As Pew reports, newspaper circulation has plunged, with newspapers earning less now than when I was born. Newspaper employment has dropped by more than 60 percent since I graduated college.

But getting my news from a phone rather than a paper doesn’t make me a yute at all. As Pew also notes, use of social media varies dramatically by age group. Old people don’t use Snapchat; youths use it a lot. YouTube is popular for olds; it is ubiquitous for the young. Only Facebook—cringe as it is—has cross-generational appeal. (If anything, this data probably underestimates TikTok for the college demo.)

Why belabor this point? Because much of college instruction still assumes, even relies upon, the media consumption habits of mid-20th century America. A video I recently watched that was meant to help college students learn to read began by saying, “Don’t read for class the way you read a magazine.” But the kids don’t read magazines.

In fact, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the kids don’t read. In time surveys, they report spending just 14 percent of an hour — eight point four minutes! — reading for personal interest a day.

Basing instructional interventions by contrast with “the way you read a magazine?” You may as well be talking about the way you read cuneiform.

The causes of this decline are manifold and I’m sure there’s a scholarly literature. My concerns are more immediate. I have to teach classes, and yet every year I share less of a common reading background—not just substance, but even the idea of reading periodicals—with my students than the last year.

The effects of this are profound. I used to base my US Foreign Policy class in part around reading and engaging with a single nonfiction book; once, a student told me it was the only time she had ever read a nonfiction book cover to cover. I cut out the book during pandemic because the course reading load, which hadn’t changed otherwise, seemed too much for the emergency. I’m not reinstating it because I heard loud and clear that the downsized reading load was still too much for students. Colleagues at other institutions report similar trends.

(By the way, it’s easy to dismiss complaints of this kind with the fake Plato quote—and it is fake—decrying the supposedly worse manners of kids today. “Ah,” says the wise man, “the old have always complained about the young.” Yeah, but in this case we’re talking about a pretty rapid shift taking place over a few years backed up by statistical evidence, so I’m pretty sure that this, unlike the fake Plato quote, is real.)

Moreover, I’ve started doing more direct reading instruction, including exercises to help students identify the thesis of a given reading and to teach the conventions of different forms of writing. This may seem basic, but it really isn’t: even within the kinds of general-interest readings I assign, the conventions of longform journalism, opinion writing, analytical essays (think Foreign Affairs), and straight news stories are as different as lyric poetry and free verse. And if you don’t know what’s going on, you really can’t read these, even if you can put every word and sentence together.

To be clear, I think this is valuable and useful for students, and I’m not blaming them. (I might blame their school systems a little bit.) But I do sometimes feel like the main character in a Fifties sci-fi short story or Twilight Zone episode watching a new culture emerge as the young interact with technology. To quote an ancient television show:

The episode of The Simpsons from which this was taken first aired in 1994, 28 years ago. This meme has gotten a driver’s license, graduated college, and is about to finish its doctorate and teach students who think that Family Guy is that really old animated show for Millennials.

I want to feel like I’m inducting students into the adult world, a world of The New Yorker and Journal of Conflict Resolution and distinctions between the news and opinion sections of The Wall Street Journal—the advanced version of the print culture I was raised in that the Internet has expanded, deepened, and mostly improved since I was young. But I also worry that I’m just teaching people how to use cuneiform when the printing press has been invented, and that all of the knowledge I have about how to engage with texts and the institutions that produce them is a wasting asset in a world of algorithmic curation of videos and social media.

Teaching requires meeting the students where they are. But what if the distance is so great that it can’t be traversed in a semester? And what if the terrain where they are is too different for the edifice you’re trying to build with them?

Gonna assign this at the start of this semester's Media & Politics in Europe class, and hope to prompt some discussion. I'm then still going to make them read at least some book chapters and such, because that's where the information they need is.

If it's any consolation, I'm a 20-year-old reading this article for 'personal interest'