Kevin McCarthy: Cannon Fodder

Or, I heard you like political parties, so I put a political party in your political party

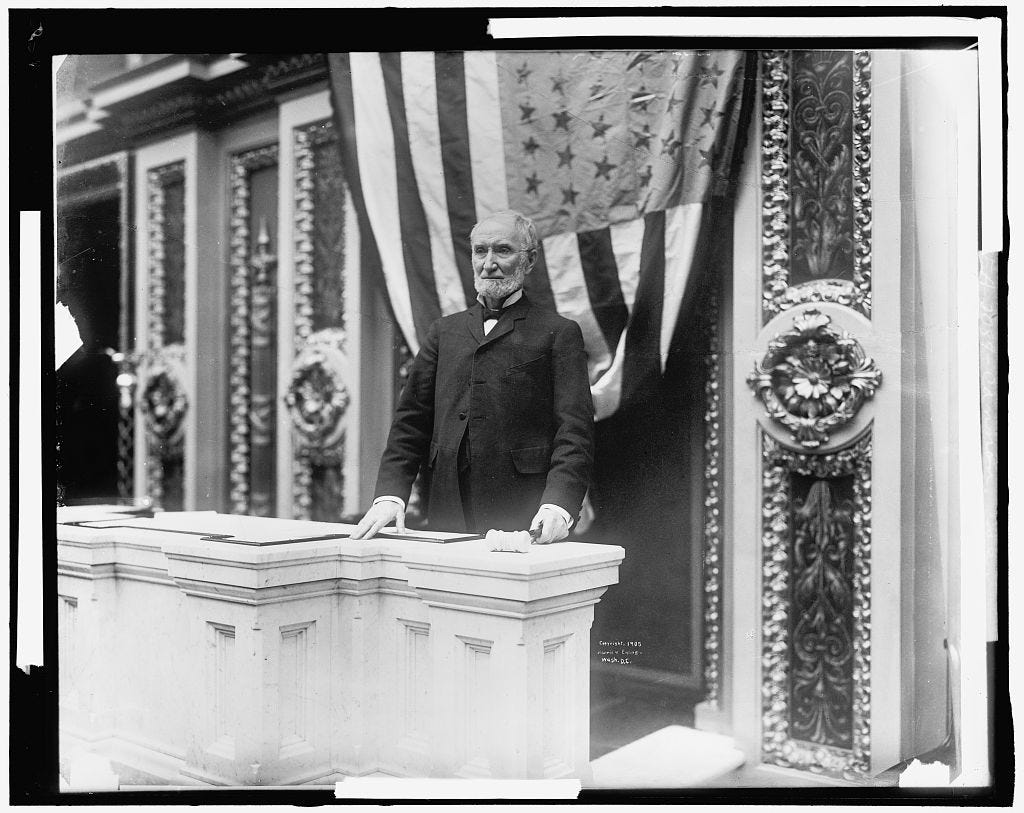

Back when men were men and Arizona was a territory, Rep. Joseph Cannon (both a Representative, from Illinois, and a Republican of the rock-ribbed sort) ruled Congress as Speaker. Cannon presided with a fist so strong that calling it “iron” would underplay its strength. In his steel grip, members were assigned to committees and allowed to speak on the floor as he saw fit. (Among other assignments: he gave himself control of the Rules Committee.) When votes were cast by voice, it was Cannon, not the members, who decided which side had prevailed. (“The Ayes make the most noise, but the Nays have it,” he once ruled.) From 1903 until 1910, Cannon was the sort of legislative leader that supporters feared and opponents loathed—which is a good way to be remembered with the rarest honor Congress can bestow: the naming of an office building.

Eventually, Cannon’s grasp proved too tight. An insurrection led by Nebraska Republican George Norris led to his overthrow (and a reform of the chamber’s rules to weaken the position of Speaker).

The story of Cannon’s overthrow forms one of the canonical studies of how members of the House of Representatives and leaders (or leaders-manque) of that chamber contend over power. It also forms one of the major cases in Ruth Bloch Rubin’s Building the Bloc, an excellent study of intraparty organizations in Congress. Rubin’s work, mostly historical, proves unusually relevant in understanding the disarray in which House Republicans find themselves this week. Kevin McCarthy has already earned his place in the history books (and, more important, the political science journal articles)—but unlike Cannon, he doesn’t necessarily get to be Speaker first.

Rubin’s task is to “show how rank-and-file lawmakers [use] intraparty organization to resolve several serious collective action and coordination problems that would otherwise prevent them from effectively challenging congressional leaders for legislative control.” In other words, you would think that leaders, once chosen by the House, would be responsive to the party that elected them, but in reality (and, more important, in theory) things are not so simple.

Consider the constant fight between centrist members of the House and party leadership. The desires of the median member of the chamber (that is, the most centrist member of the House) are not the desires of the median member of the party caucus that chooses leadership (that is, the member at the center of the majority party). The chamber median member would prefer leadership to pay attention to her desires, but making plausible the only threat she can play—that she will withhold support for the party—leaves her too vulnerable to punishment and too exposed in other ways. The only way to avoid this fate is to create an organization of similarly-minded members to unite and force leadership to give in to them.

Rubin explores how members can come together in these causes to shape policy and procedure in the chamber. Her book represents an original and well-researched argument about what particularly powerful blocs, like the Southern conservatives of the mid-twentieth century Democratic Party or the Blue Dogs of a seemingly distant (but quite recent!) Democratic past, are actually doing, and why it can be so hard for leaders to bring them to heel. It also explains why dissatisfied members at the party’s fringes form and act in groups: their membership allows them to avoid punishment and to bring greater pressure to bear, but it also requires them to pool their efforts and form common interests and identity. If you come at the king, you best not miss—and if you come at Speaker Cannon, you best have more than just George Norris on your side: you need an entire party bloc.

The past several years have provided a boom for intraparty organization, Rubin writes:

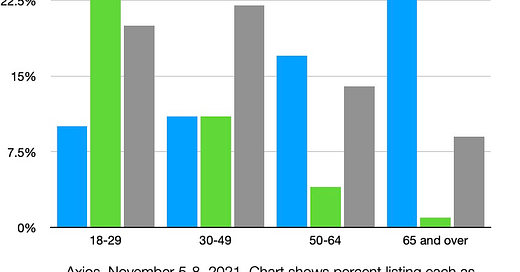

[P]olarization has shifted the locus of infighting from a conflict between centrists and party mainliners to one between party mainliners and hardliners. Like their now politically endangered centrist colleagues, party members located spatially at the extremes of their party coalitions have embraced organization—forming groups like the Democratic Study Group, Republican Study Committee, and House Freedom Caucus—to further their own policy and electoral goals.

And so we arrive at the paradox of how Kevin McCarthy can be beclowned at his moment of triumph. At the apex of congressional polarization—at a time when the chamber’s swapping of majority parties means that it will be moving not to castigate but to celebrate the January 6 assault on the Congress—there appears to be nothing that McCarthy can do, no level of abasement or appeasement he can offer, that will satisfy nineteen (or twenty) members of his caucus, acting together, to convince them to vote to let him be Speaker. McCarthy looks less like a czar and more like a pretender to a throne.

(Pobre McCarthy! They don’t even name conference rooms, much less office buildings, after people who can’t even corral their caucus into voting for them.)

What do the rebels want? Well, in general they want more extremism. Unlike the centrist chamber members, who are therefore at one extreme of their party, the rebels tend to be the more extreme flanking members of the entire caucus. (Although not entirely: for every Rep. Biggs or Rep. Norman, among the very most conservative members of the House and leaders of the revolt, there is a Marjorie Taylor Greene and a Ronny Jackson, equally extreme but so far stalwart.) It remains to be seen if there are compromises that can be drawn—or that McCarthy can guarantee with his damaged credibility—or whether the fight will have to be worn down by attrition.

What happens next? Well, this is a branch of political science that is a little better at explaining the range of possibilities than telling us what happens. Rubin’s book suggests that “forming and sustaining organizations of this kind requires participants to sacrifice time, energy, and some degree of individual autonomy” to fight as a bloc—and so “party dissidents are likely to adopt less costly modes of organization before turning to more formal procedures.” But it seems that, with yesterday’s historic three votes without an election, we are already into the costly part of bargaining—and McCarthy has been substantially weakened. You don’t need a Ph.D. in political science to assume that the longer this is drawn out, the greater the pressure for McCarthy to bow out and for the rebels to accept a substitute.

At the very least, the rebels have shown that they have a good deal more credibility in their threats to withhold support for anyone—even someone supported by ninety percent of their caucus—than one would have expected. To force a vote on a Speaker three times is not a bluff. And that means that the likelihood of floor action on major issues (like, say, the debt limit) is much lower than one would have expected going into this session—and the corresponding need for constitutional flexibility by the Biden administration (like, say, ruling that the debt limit is unconstitutional) is much higher.

Endnotes

The goal of this essay is to persuade you that we shouldn’t send human beings to Mars, at least not anytime soon. Landing on Mars with existing technology would be a destructive, wasteful stunt whose only legacy would be to ruin the greatest natural history experiment in the Solar System. It would no more open a new era of spaceflight than a Phoenician sailor crossing the Atlantic in 500 B.C. would have opened up the New World. And it wouldn’t even be that much fun.

—“Why Not Mars?”, Idle Words