What Biden's Decision Says About Picard's Decisions

Sometimes, reality is the mirror for popular culture

I’ve written a little and been cited a lot for a piece I co-wrote about the politics of popular culture. One of the less-noticed spinoffs of that piece was a blog post I wrote (apparently before publication, although I swear the post was written after the article) imploring scholars writing about these topics to stop talking so much about nerd catnip like Star Trek and instead talk about the actually popular cultural artifacts of various societies.

I’m going to break that rule in this essay. Partly, that’s for solid substantive reasons—I think that this subject matters! Partly, it’s because this newsletter exists in a liminal space between scholarship and writing for fun. Mostly, it’s because I’m still very angry about Picard, a show that has weakened Star Trek a lot—and which did so in a way that reality has since demonstrated was the very wrong choice.

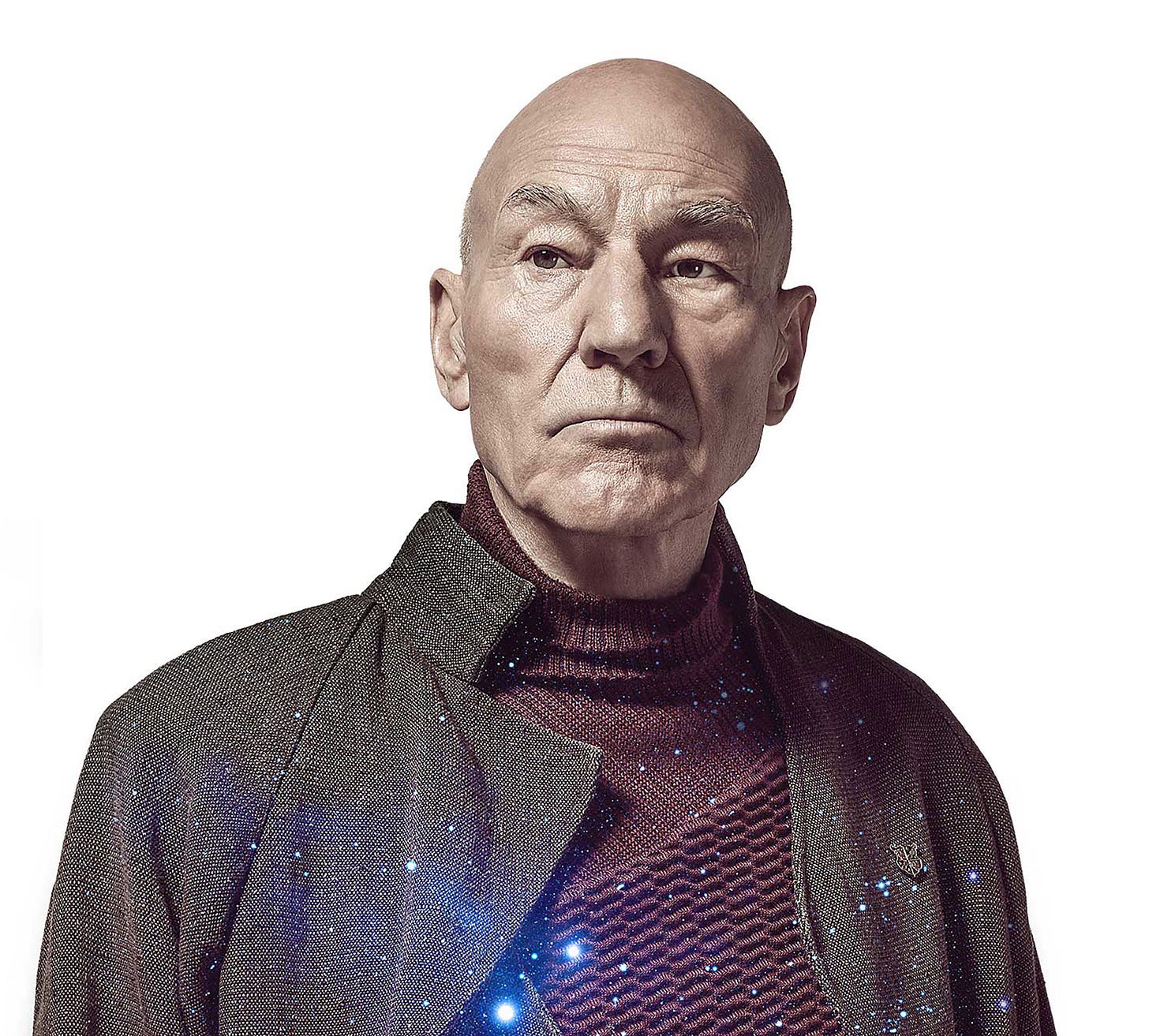

Picard, if you’re unaware, is a streaming show currently housed on Paramount+. It ran for three seasons and chronicled the adventures of Jean-Luc Picard, the principal character of Star Trek: The Next Generation and several films involving that property. Played by (Sir) Patrick Stewart, Picard represented an apex of a certain form of cerebral (hetero)masculinity: steady under pressure, intellectual but able to act, pragmatic while moral. The character, to be sure, had flaws: distant from his subordinates, unable to balance work and “life”, and reluctant to confront his emotions instead of shoving them aside. Still, in all, he represented a different form of captain and leader than James Kirk—even if “emotionally distant sage” is not exactly a departure for genre fiction, it was a significant enough change to mainstream science-fiction that producer Gene Roddenberry made Stewart, who has been bald for decades, screen-test a wig.

Picard the show portrayed Picard’s later life after leaving the Enterprise and, in the first season at least, Starfleet, the fictional NASA/(Royal) Navy mashup organization that provides the Star Trek universe with its organizational substrate.

The premise had promise. Popular culture does not provide many examples of transitions between stages of life, and especially moving from one’s prime to, let’s gently say, one’s post-prime. (It also doesn’t do a good job of showing what the executives of any organization larger than a dozen or so members actually do, but that’s probably a limitation of the genre—even if Star Trek: Necessary Bureaucracy would have numerous opportunities for presenting the tradeoffs between ideals and necessity that give the franchise its most important crises.)

In the event, Picard the show punted on demonstrating a graceful or even an honest transition from one stage of life to another. Ironically, in failing to do this, it failed at a task that the original cast of Star Trek succeeded in twice: with the midlife crisis/coming-of-age film Star Trek II (which was, ultimately, about embracing the no-win scenario of life) and the detente/career-ending parable Star Trek VI (similarly, ultimately a film about resisting and then accepting change).

Unlike the 1960s cast, then, the Next Generation never knew how to pave the way for the next generations. Picard displayed this pathology to extremes. New characters were introduced, but strictly as MacGuffins or supporting players for Stewart’s Picard, who remained the center of the action and—horribly enough—a lead even in action sequences.

It’s relevant here to note that Patrick Stewart is 84, which means he was in his very late 70s when preproduction began. It is not, I think, ageist to note that 80-year-olds cannot pull off the kinds of stunts that 50-year-olds can—and even the assistance of actual stunt people still requires some limiting of flexibilty to preserve some suspension of disbelief. The power and range of older actors, like older anythings, comes, when it does, from their ability to draw on experiences and insights that younger actors cannot embody quite as well—not least the experience we all eventually feel of losing touch with the Zeitgeist, of feeling like our habits and values are out of step with the present day.

There’s a lot of drama to be mined from that dissonance; Captain America, for instance, in its various iterations has relied on the disjuncture between the embodiment of foundational ideals1 and the obvious shortcomings of the present day. Picard played with these tensions, noting the Federation’s abandonment of a former enemy enduring a humanitarian crisis and showing its fictional utopia banning entire forms of life after a 9/11-style terror attack, but they were ultimately relegated to the sidelines throughout the show’s extremely uneven three-season run. The culmination of the show’s pathologies came with the conclusion to its third season, in which only seasoned adults who were unexposed to new technologies could come to the rescue aboard a resurrected U.S.S. Enterprise-D. That ship had been sacrificed in the crew’s first movie to some dramatic effect; bringing it back led to a great deal of fan service but also underscored the fact that the series had no new ideas left to present.

What Picard should have been is a one-off character study of how to leave the scene gracefully—how to handle no longer being the star of the series and instead letting others have the limelight. It could have embraced mortality, along the lines of one of the Trek movies’ few quotable lines: “time is a companion who goes with us on the journey and reminds us to cherish every moment, because it will never come again. What we leave behind is not as important as how we've lived,” Picard tells his first officer in the first Next Generation film (in the wreckage, by the way, of the Enterprise that will later be restored for the memberberries).

Here it is that reality has outdone fiction.

Anyone who becomes president besides Gerald Ford has been consumed with the quest for years if not decades. Wanting to be president and then being president constitutes an identity, a drive so enthralling it beggars belief. Leaving the presidency—giving up the reins of power, or even the chance at holding onto them—equally constitutes an identity crisis.

President Biden’s path to giving up the Democratic nomination for president was far from smooth. By all accounts, it seems to have involved anger, resentment, and struggle. Given reports of presidential temper in general, I would not be surprised if we learn that June 2024 featured periods of sullenness and outbursts.

And yet.

Eppur si muove! The president relinquished the nomination to a successor. Under the circumstances, this was no purely altruistic move. It both guaranteed greater loyalty from his second and also headed off the “open convention” that some donors had wanted as a means of choosing a different candidate.

And yet.

One cannot relinquish anything without struggle both internal and external. That is drama. That is drama, in this case specifically, about accepting the reality of aging—that even if one feels oneself to be the same, others’ perceptions, rightly or wrongly, have changed who you are. That is no small thing.

Picard could have dealt with these issues. Instead, it went with denial. There was no forcing event that caused Picard to confront the change in himself and his circumstances; on the contrary, the show tantalizingly promises that in one’s old age one can recover one’s youth and vigor easily. That is less realistic than the transporter or warp drive.

The last chapter is the hardest to write, all the more so in an autobiography. We want to think there’s something left to say. Eventually, there is not. Accepting that is the last test of maturity. Denying it is the delusion of the adolescent.

And, yes, I think the New Deal era ethos of Steve Rogers is more “foundational” to American identity than the Revolution or the Civil War; the “Spirit of ‘76” resonates less than punching Hitler.

I'm a bit behind on Strange New Worlds because I'm waiting for my spouse to catch up, but it's interesting that the Balance of Terror episodes ends up making this case more than Picard did. That said, the case loses some of its power as because as much as I love Pike, it's easy to accept that it makes sense to step back with grace when I already love his successors.

I'll add one other self-indulgent bit of popular culture contemplation. In the Shogun version of the 2024 election, it was Biden's plan to wait until Trump appointed JD Vance before stepping back. But while I'm enjoying Shogun, and we did see the brilliant Inflation Reduction Act senatorial maneuvering, any shows where clever cards close to the chest maneuvering that doesn't fail like at least a third of time risks leading to a seriously distorted view of politics.