Left Behind

Consuming at the end of the American Century

In this newsletter:

the CCP succeeds

the rise of global Chinese coffee brands

Labubu and gacha games

Trump as Tokugawa

The real work of international change happens in the background. Dramatic scenes take place on a stage already dressed by gradual shifts in power and potential. Sometimes, the shift is so gradual that observers do not notice it. Sometimes, the shift is so challenging to their beliefs that they ignore it—or assume that it can’t keep going forever.

So let’s talk about the rise of China.

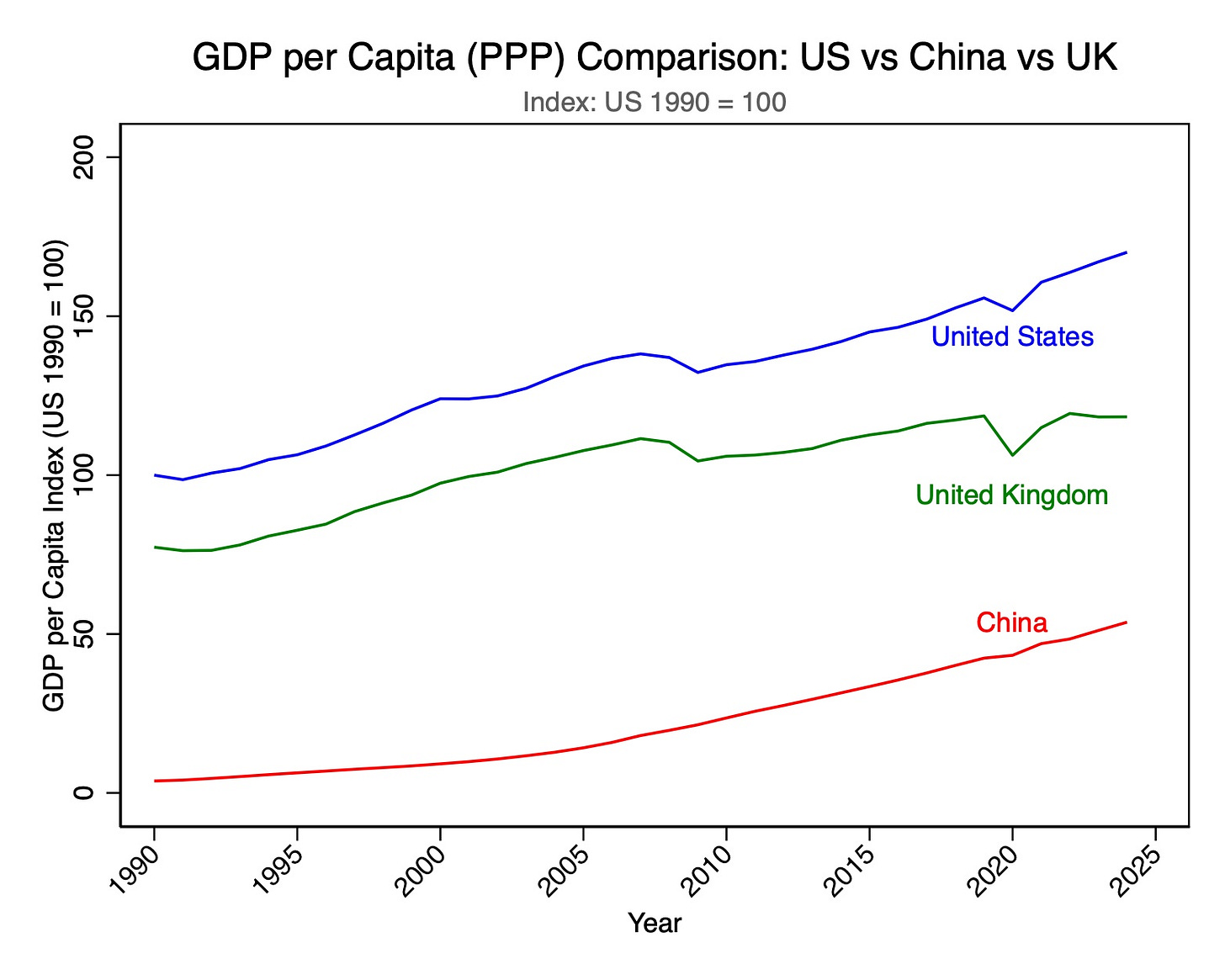

The rise of China is the most important story of the past generation. In 1990, China didn’t rank in the top-10 economies—behind such powerhouses as Iran and Spain. These days, depending on the measure, it’s the largest or second-largest global economy. The rise has been so consistent and so dramatic — less than the span of an adult lifetime (mine, at least!) — that I still think it hasn’t registered. Our baseline expectations about the world are set in early adulthood, and updating those priors can be difficult.

It’s easy to exaggerate the transformations of the People’s Republic of China. The PRC isn’t full of fifty-foot giants with 160 IQs. Its per-capita GDP is on par with North Macedonia (or Serbia, at nominal levels). Its space program isn’t meeting expectations.

On the other hand, I mean, come on: if a fourteen-fold increase in GDP per capita isn’t impressive, what is? And along with that transformation has come increases in hard power, from a growing nuclear stockpile (hey, did you know we live in a tripolar nuclear world now, or at least will shortly?) to a rapidly growing navy and air force.

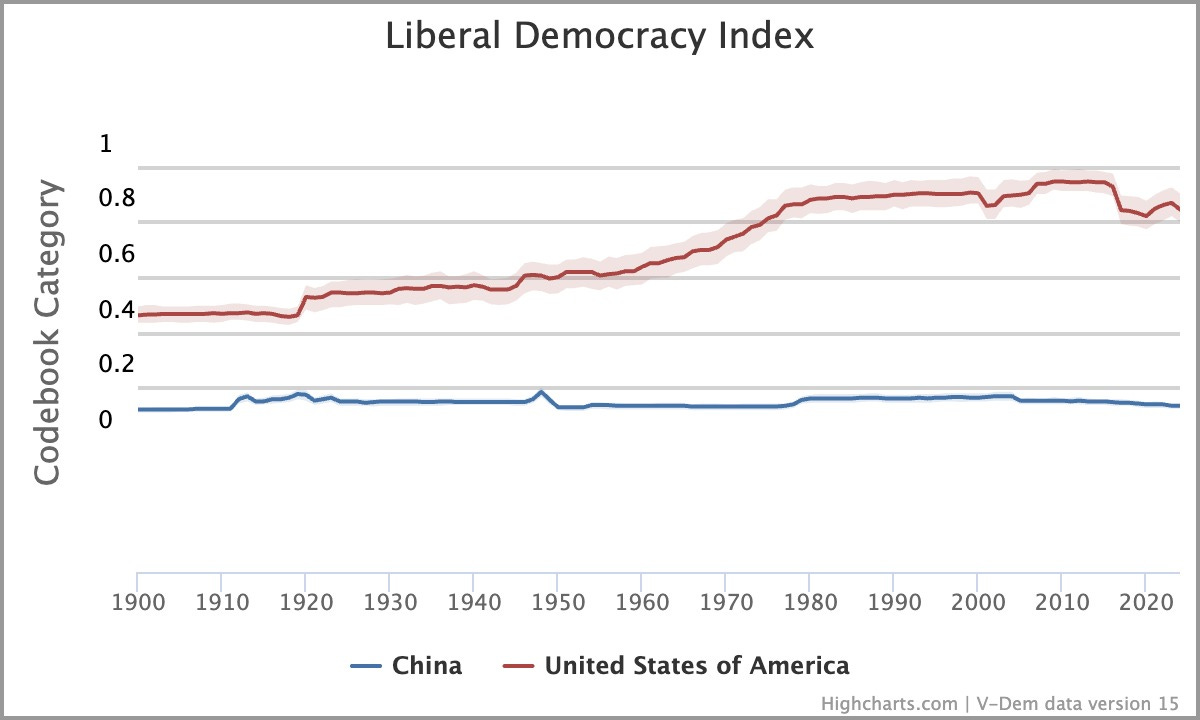

And more to the point: it wasn’t supposed to be like this, at least according to mainstream Western thinkers at the end of history. U.S. strengths after the Cold War were supposed to lock in a liberal global structure anchored by the United States. So how do we understand era in which liberalism is in retreat and China is becoming a dominant global force while the United States abandons entire fields of competition?

The first step is admitting you have a problem.

The other day, Kaiser Y Kuo wrote an excellent essay about what it means to accept that China’s modernization under the Chinese Communist Party has succeeded on its own terms. The dream of the Nineties—that liberalization and moderation, maybe even democratization, would follow economic growth—has been shown, so far, to be a false belief. Indeed, not only has the People’s Republic not democratized, the United States has de-democratized (per the Varieties of Democracy Index) over the past 35 years, with a lower quality of democracy now than in 1990:

Are you more certain that the United States will be a multiparty democracy in 2040 or that China will be a unitary state under the leading role of the Communist Party? What odds would you take on each bet? Are they higher or lower than you would have accepted in 2015?

To be clear, I’m not saying that my answers to the first two questions are “Definitely China” and “overwhelmingly pro-CCP” . But I definitely think my expectations have changed on the third question, particularly regarding China’s future. And if yours haven’t, then you should really think hard about whether your beliefs are falsifiable.

Further, at this point, China’s rise is a secular fact, and even if there were to be some sort of upheaval (with or without regime change) that froze China’s GDP per capita at its current levels, China’s economy is so large and its dominance in so many industries so pronounced that the effects will continue to be felt for decades. In this way, China’s rise is like the other major trend of the past thirty years — global climate change — in the sense that the changes visible now reflect causes manifested over decades and with long-term consequences we can perceive only distantly.

The rebalancing of wealth and power from the West that China’s rise entails is not just something easily contained within a rubric like “great-power competition”. It is closer to a global transformation. And like climate change, it is not a shift within Washington’s power to stop, only to adjust to in one way or another—productively or not, successfully or not. (Note again that this does not imply “accommodation” or “appeasement” are the only options, but it does imply a much narrower set of paths to success, however, defined, than would have been possible in, say, 1990.)

As the United States adjusts to these changes, Americans face a world growing strikingly and immediately away from them. It is worth remembering Henry Luce’s description of U.S. influence in 1941:

American jazz, Hollywood movies, American slang, American machines and patented products, are in fact the only things that every community in the world, from Zanzibar to Hamburg, recognizes in common. Blindly, unintentionally, accidentally, and really in spite of ourselves, we are already a world power in all the trivial ways.

This was a little exaggerated—but really only a little. These days, however, you could substitute “Chinese” for “American machines” and you’d be more accurate. Jazz is gone, replaced by hip-hop (and isn’t that a rich statement about the racial dynamics of American soft power), which in turn is substantially localized and indigenized around the world. In popular culture, the United States does remain a force, one still more influential than South Korea or Japan, but it is far from the hegemonic player that Luce claimed it was.

Transaction by transaction, moreover, U.S. influence is slipping away in relative, and maybe absolute, terms. If someone around the world is buying a car, there’s a better chance than ever they’re buying a Chinese make. Ditto for consumer electronics. Chinese firms, like the Chinese economy, are moving up the value chain. Anker, a brand I used to associate with power banks and decently made electronic accessories, now makes headphones and other finished consumer products. It is, in short, becoming a brand—the point at which industrial potential unlocks commercial premiums.

Nor are Chinese firms limited to competition in the making-stuff space (although I would like to observe, in passing, that Chinese manufacturing is also no longer defined by cost advantages but rather by the size and unmatched sophistication of its industrial economy).

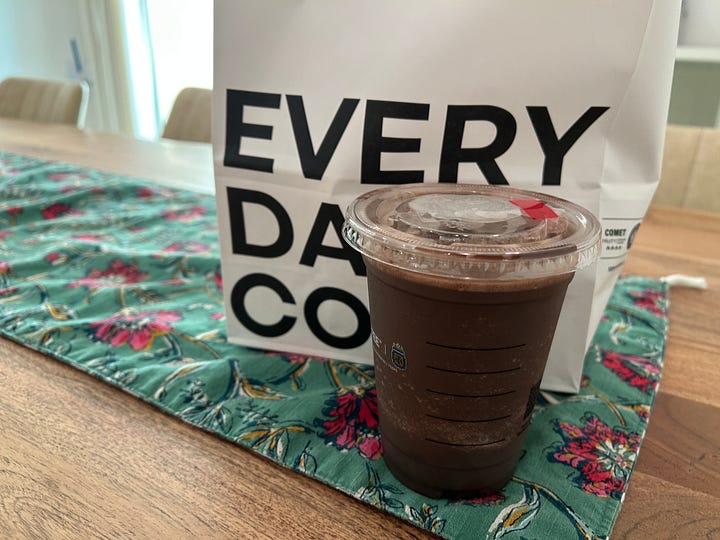

Consider Cotti Coffee, one of the two Chinese coffee brands (with Luckin) going global—depending on which site you consult, it has either at least 7,500 or 10,000 locations (compare Starbucks at 38,000).

For the first several months of our time in Doha, we ordered Tim Horton’s every weekend. Tim’s costs about 17 riyals per latte. It was nice! Sometimes it’s nice to have something ordered in!

Several weeks ago, we pivoted to Cotti Coffee. Cotti is cheap—about 10 to 13 riyals per drink. It’s fast—maybe ten minutes faster than Tim’s. And it is not only “good enough” but good, very possibly better than Tim’s on an absolute scale.

Think about how different a story this is from 1990s-era stories about fast-food expansion—like how every story about Beijing would note the McDonald’s near Tiananmen Square or about Moscow would note the Pizza Hut. A story about a Cotti Coffee opening in Flushing isn’t exactly as dramatic but it does suggest that something is changing.

And, as I’ve written repeatedly, outside the United States the changes are way more obvious. As far as I can tell, there’s more Cotti locations in Doha than in New York, and I believe they’re all new. If you visit one in a mall around these parts, you will probably pass a few Jetours (Jiètú), some Cherys, and maybe a few Geelys in the parking lot. There might even be a Ford.

Other changes seem more superficial, because we are embarrassed to admit that diversions matter for how we see the world. Miranda Wilson writes in The China Perceptions Monitor today about Labubu, a Pokemon/Beanie Baby hybrid (sorry, that’s the best I can do!) that is huge in China and around the world. This trend has penetrated to the United States, but, again, as best as I can tell to nowhere near the same degree it has globally. (I was originally planning to anchor this essay on Labubu, but Miranda did a better job!)

Similarly, the size of China’s mobile gaming sector is enormous. Gacha games like Genshin Impact and Honkai: Star Rail earn hundreds of millions of dollars a year. Rather like Labubu’s “blind box” model, gacha games involve players spending money in-game to buy chances at winning highly valued items in the game. This is a sector of efforts in which China is not just a competitor but in some ways a dominant rival.1

And then there’s LLM (AI) generation, in which Chinese firms rival American-led ones (reportedly at lower costs). Moreover, for open-source models, Chinese efforts are trouncing all rivals.

All stories about Chinese corporations scaling fast should mention, of course, that there’s probably some currency manipulation and maybe some tariff pressure and often non-commercial sources of cheap capital at play. Yes, sure, fine. But eppur si muove: the products exist. They’re high quality, or at least good enough as makes no difference (yes I am still wearing my Huawei watch in preference to my old Apple Watch). People spend real money on them. And they spend a lot more now than they did ten years ago.

This is a real change. “Made in China” used to be a joke or a signal of poor quality. That’s far from guaranteed anymore. Some Chinese firms are world-leading; some are strong competitors on quality and others on price. As Miranda Wilson quotes a consultant as saying, “BYD, DeepSeek, all of these companies have one very interesting thing in common, including Labubu. They're so good that no one cares they're from China. You can't ignore them.”

So where does this leave the United States in the era of Trump and Trumpism?

This is an informal essay, not a peer-reviewed manuscript, so I can be a little more wild than I would normally be. I’m going to throw out a hypothesis: Trump is the American Tokugawa and MAGA in foreign policy is trending toward becoming a neo-sakoku policy.

How? First, Trump seems uninterested in playing a constructive global role. He seems much more interested in paring back global capabilities and responsibilities while focusing on ways of cementing his own power. Moving away from global alliances and relations makes sense as a way of closing off exit options and threat vectors; it also allows him to use policy and enforcement as a vehicle for rent extraction. Simultaneously, persecuting the intellectual class and closing off exchanges with external institutions insulates the regime from criticism and challenges, while promoting the centralization of power and authority outside of regular institutional channels. Just as “opening up” was a major shift in China’s foreign relations intimately related to domestic politics, “closing down” in Trump’s America can’t be understood outside of power-seeking.

Don’t take the parallels too seriously. Sakoku involved sequestering foreign influences to a very small physical and temporal extent; that isolation lasted from the 17th to the 19th centuries (Western reckoning). I don’t think that it’s likely that, as a result of Trump, all American contact with the outside world will be reduced to sporadic trade missions in Miami for the next few hundred years.

But on the other hand I do think we should start looking toward other, sometimes less familiar precedents to understand the U.S. moment. For example, U.S. history cannot furnish any good parallels to the kind of restrictions and de-linking from the outside world that Trumpism II: Boogaloo has entailed so far. The casual internationalization of many universities and other institutions that marked them as advanced before 2025 is now a liability; as I’ve mentioned before, it is already noticeably harder to conduct business with U.S.-located scholars, and I expect this trend will continue over the next few years. This is the sort of policy you need to look to other regimes for precedents. (Those examples aren’t happy ones, by the way!)

All told, these trends all point toward a world in five or ten years’ time that is much less structurally disposed to work in Americans’ favor, which sets up a possible self-reinforcing cycle in which the appeal of isolation relative to internationalism grows accordingly. By contrast, China—despite not being a particularly extroverted power—will see its structural influence wax tremendously over that period. And structural changes work according to a Matthew effect in which growing connections have their own self-reinforcing properties: as you get more used to working with Chinese standards, Chinese firms, and Chinese tech, it gets easier to work with other Chinese institutions and ideas. (Americans of all people should know this.)

The trends I discuss here, then, point to a scenario in which the United States is weakened but not for any particular offsetting benefit. When and if the United States exits Trumpism, then, it will rejoin a world already in progress—a world that no longer orbits the United States, a world in which “American” is no longer the reference for all things (except measurement), a world that is actually internationalized as opposed to just Americanized. It will be a world that left America behind.

Thanks to Jordan C. for this point!

The end of the American Century does not imply the beginning of a Chinese Century. The global economy is a lot more than China and the US: the EU, India, Japan, ASEAN etc are collectively quite a bit bigger in most respects, except some manufacturing industries.. And despite the examples you mention, China is still less culturally salient at a global level than any of these, or even, in important respects, small countries South Korea.