One of the fun assumptions of many social science theories is that actors know what they need to know. One of the first things you notice in any real world situation is that they absolutely do not. Actors have a pretty good sense of what they want—to be re-elected, to be promoted, to be rich and healthy, etc.—but often they do not even know how to map that general interest into specific preferences in a given situation. (For instance, I would like to have an endowed chair at Stanford. I have only the most underpants-gnome idea of how. Maybe I should publish some more, I guess.)

Sophisticated theories of foreign policy analysis and so on often recognize the gaps in actors’ knowledge, and there are great debates about how, exactly, to recognize the fact that hardly anyone knows what they’re doing, what they want in a situation, or how to craft a strategy under uncertainty. I tend to think that people fall back on habit, “precedent”, and deference to confidence because thinking is really, really hard and responsibility for decisions is really costly, but every now and then there is someone who does understand the situation and complicates even this rule of thumb.

One example of “not knowing what’s going on” I encountered today involved Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, the legendary (and infamous) courtier to several presidents from the 1960s onward. Kissinger was a veteran, a Harvard international relations expert, and, most important for this context, the most powerful national security adviser/Cabinet official in foreign policy of, perhaps, the entire twentieth century. His whole brand was a combination of wit, calculation, and literal savoir-faire—that is, knowing what to do.

In August 1976, Kissinger and the Ford administration confronted a crisis. U.S. officers had moved to prune a tree blocking UN troops’ view of North Korean movements in the demilitarized zone (DMZ) of the Korean Peninsula. This routine bit of arboreal maintenance became a flashpoint when North Korean troops beat the two officers to death in full view of UN observers.

Kissinger and other members of the Washington Special Actions Group (a crisis committee in the Nixon-Ford years) moved to determine what the United States should do in response. Admiral James Holloway, chief of naval operations, suggested one response: “We could go from DEFCON 4 to DEFCON 3.”

“What would that do?” Kissinger mused. Holloway noted that, without other context, the North Koreans would “not react at all.” Another member of the committee interjected to recommend finishing the tree job: “we should cut the God damn thing down.”

Secretary Kissinger: I am in favor of that too but I don’t think we should do anything about the tree until after we do something with our forces. What is the meaning of the DEFCON alert stages?

Adm. Holloway: 5 is normal and 1 is war. Stage 2 means that war is inevitable and stage 1 is when the shooting starts.

Mrs. Colbert: If the alert were moved up to 3 how would the media and the U.S. people react to that in this campaign year.

Secretary Kissinger: That has nothing to do with it. The important thing is that they beat two Americans to death and must pay the price.

“What is the meaning of the DEFCON alert stages?” Please bear in mind that by this point Henry Kissinger had been the key aide in the White House foreign policy and national security operation for nearly eight years. He advised President Kennedy during the 1961 Berlin crisis. He had written several books about nuclear strategy. He would have been the first call for either Nixon or Ford during any nuclear crisis—and, in fact, was. And yet he had exactly the same confusion about DEFCON levels as any TV screenwriter!

As a bonus note: That’s State Department veteran and National Intelligence Officer Evelyn Colbert chiming in with the most glaring domestic-politics intrusion I’ve heard of since Susan Rice mused whether calling mass killings “genocide” in Rwanda in 1994 would influence the congressional elections.

Yet I don’t think Kissinger’s confusion is the biggest “do they know the rules” moment I’ve ever seen. That has to go to the only person in U.S. history who was more prepared for foreign policy questions than Henry: George H.W. Bush, who, by the time he became president, had been vice president, ambassador (functionally) to China, ambassador to the United Nations, and a member of Congress.

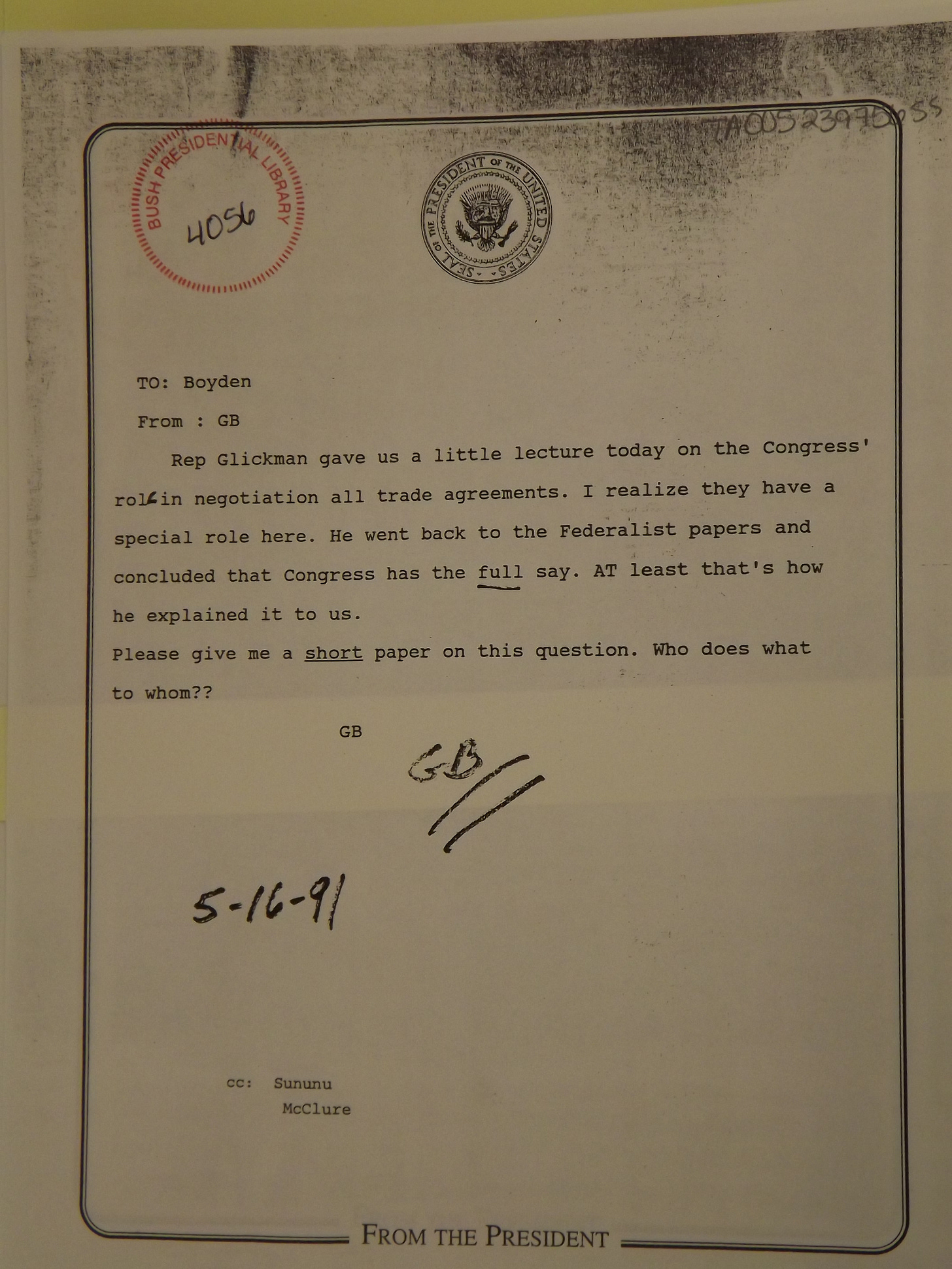

In May 1991, thanks to a document I found (many moons ago) in the George Bush Presidential Library, Bush asked White House counsel C. Boyden Gray1 what the hell was going on with … the foreign affairs constitution:

Here’s the text:

To: [White House Counsel C.] Boyden [Gray]

From: GB

Rep. Glickman [a Democratic congressman who would later be Secretary of Agriculture] gave us a little lecture today on the Congress’ role in negotiation [sic] all trade agreements. I realize they have a special role here. He went back to the Federalist papers and concluded that Congress has the full say. At least that’s how he explained it to us.

Please give me a short paper on this question. Who does what to whom??

George H.W. Bush, most prepared foreign policy president (yes, probably more than Biden), asking … hey, what does the Constitution say about my role in all these trade agreements I’m negotiating? And please: keep your answer short.2

(Special bonus: oh god the amateurs are reading the Federalist Papers again. Please, MCs: call CRS when you have a question.)

As you observe the political scene, please remember: nobody knows what’s happening, including the players.

A giant in the field of presidential advising. He was very tall, is what I’m saying.

Unlike Boyden Gray. Who was, I want to reiterate, very very tall. Yes, footnote 1 was a setup for this joke.