Bad Congress, Part 3: Edmund Pettus

The Gentlemanly Paladin of White Supremacy

Over more than two centuries, more than 12,000 people have served as senators or representatives (or both)—and some of them have been traitors, malefactors, or epic assholes. Bad Congress will introduce you to America’s rogues gallery, helping to put a face on the flaws and failures of the first branch.

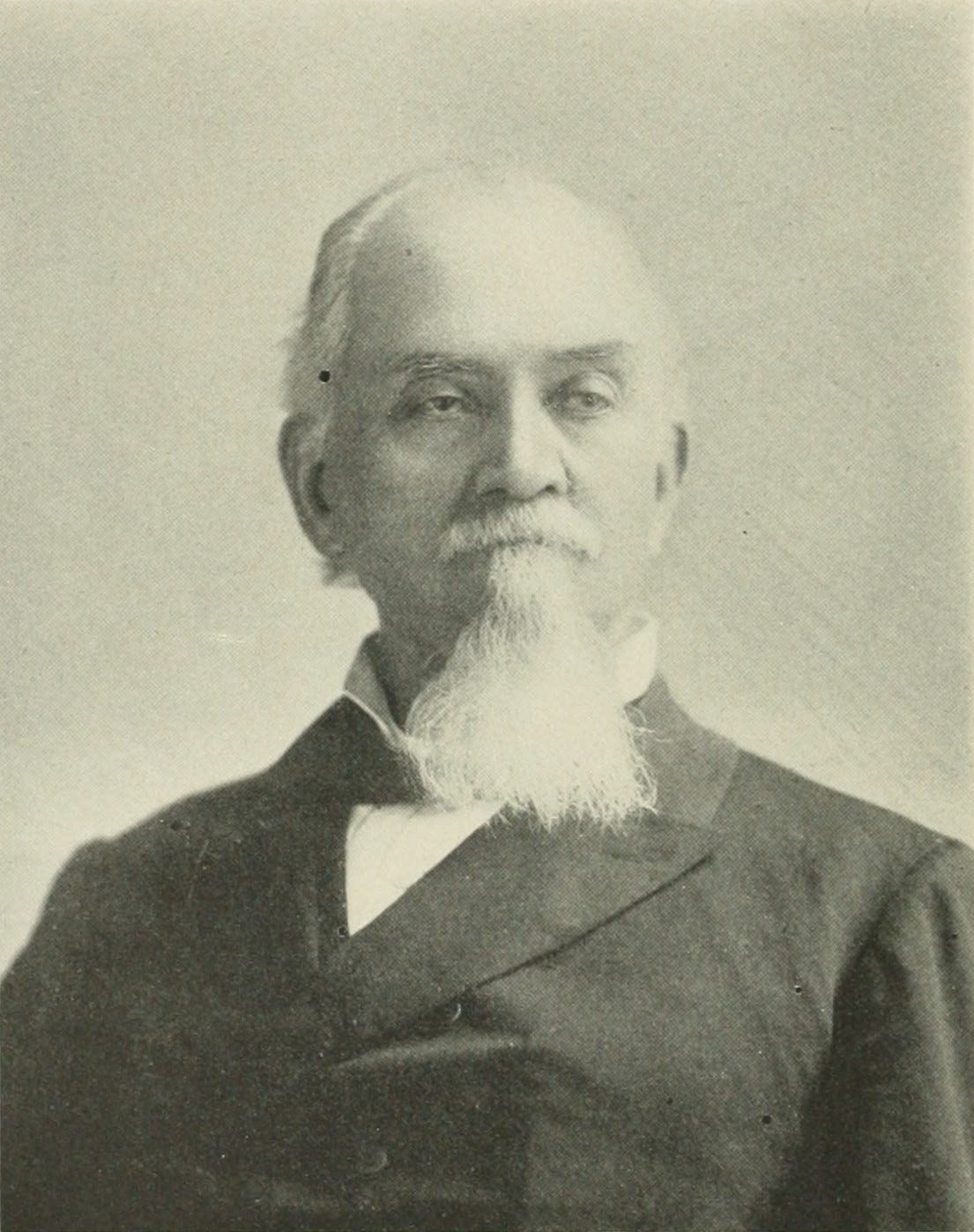

This week, we’re talking about the third in our survey of bad members of Congress: Edmund Pettus, senator from Alabama (1897-1907).

For earlier installments:

“Pitchfork” Ben Tillman (1847-1918), Senator from South Carolina (1895-1918).

John G. Schmitz (1930-2001), Representative from Orange County, California (1969-73)

Everyone was sad that Edmund Pettus was dead.

Because Pettus was a senator from Alabama, his death merited national headlines—not on the front pages, to be sure, but in the major newspapers of the time. And they printed nice things about his memory and praised what he had done for the country.

The type was easy to set because Pettus could be heralded as such a clear specimen of a noble solon whose loss surely represented a national tragedy. The Hartford Courant deemed him to be the image of “the old school Southern statesmen”.1

The New York Times echoed that Pettus “brought a glimpse of a by-gone time.” “It was not only his old-fashioned point of view and his use of political phraseology now almost forgotten,” the Times reflected, “but the very aspect of the man, which seemed to bring back the days of Webster and Calhoun.”2 The Times noted Pettus’s long friendship with his colleague, law partner, and friend John Tyler Morgan, who had preceded Pettus into the Senate by twenty years and into death by just over a month. The Times lauded the duo as having been beyond party or ideology:

Theoretically, Pettus and Morgan were Democrats, but practically they thought out all questions for themselves and decided them according to the principles which ruled their party forty years ago. They formed a third party in the Senate, aloof from either machine, and absolutely above every influence which could be brought to bear upon the ordinary actor on the political stage.

The Washington Post reprinted an essay by “Savoyard” (the Kentucky newspaperman Eugene Newman) which similarly heaped praise on Pettus as the exemplar of a type:

They were Southerners of the old South, of the cotton South—the South where there was the best understanding between the mansion and the cabin this world has ever revealed. It was the South that esteemed character more than intellect and put honor above wealth. They were the last of it.3

The Boston Globe noted that “He was loved by both blacks and whites, and could sway them by his eloquence with a power almost unexamined.”4

Edmund Pettus was a nice guy. But his statesmanlike aspect can’t save him from being elected to Bad Congress.

Edmund Pettus lived one of those full nineteenth-century lives that leaves modern man, crimped by a world of credentials and competition, astonished as to its variety. Born in 1821 in Alabama’s Limestone County (now better known as the home of Huntsville), by forty he had been a lawyer, a prosecutor, a soldier in the war against Mexico, a prospector in the California gold rush, and a judge.

When 1861 brought the wave of disloyalty that sparked the Civil War, Pettus rushed to stand by slavery and supremacy. Alabama seceded before the Confederacy was organized, and so it functioned for a few weeks as an independent republic; Pettus served as independent Alabama’s commissioner to Mississippi, where his brother John was governor. He returned to recruit soldiers for the Southern cause and became a major and then a lieutenant colonel in the regiment he helped form. Eventually, he became a general of the Confederacy shortly before the war ended.

After the war, Pettus moved to the city of Selma to start a law practice and to rebuild what had been lost. He served as a delegate (and chair of the state delegations) to the Democratic National Conventions from 1872 until 1896. Allegedly (there is some dispute), he was also Grand Dragon of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan in 1877, the same year his law partner, John Tyler Morgan, entered the U.S. Senate.

By then, Pettus was in his mid-sixties, prominent in his profession, and noted in his field. There was, however, little reason to think that he would one day be of any note beyond the sort of local fame and respect that few of us will attain.

Yet Pettus’s third act would matter more than his first two.

Alabama’s junior senator was James L. Pugh, a combative man with a biography eerily similar to Pettus’s even if one or two steps ahead of him at each turn. (Pugh, for instance, was a U.S. representative when Alabama seceded, and would soon become a member of the Confederate Congress.) When Pettus decided to join Morgan in the Senate, he had to beat Pugh. And, in 1896, at the age of 75, he did, winning first the caucus for the nomination and then being elected by the state legislature (which in Alabama sat only once every four years).

Pettus made a mark—not a huge one, but a respectable one. He arrived in the zone that most senators land on: neither famous nor notorious nor a laughingstock, but a serious player, one of ninety peers of the land with a prerogative to comment on any issue before the federal government. Those included foreign affairs, an area in which his colleague Morgan would become more notable but in which Pettus nevertheless spoke plainly and well. He made sensible comments opposing the war against Spain in 1898, firmly opposing presidential (and Republican) overreach. In 1901, with Cuba conquered and the Philippines annexed, he criticized U.S. misrule of those islands. Decrying the U.S. role in Cuba, for instance, in 1901 Pettus declaimed “This is a great nation, a powerful nation, a wonderful nation. It has the power, and it intends to take, and it intends to hold. That is the disgrace that we are bringing upon the American name.”

(Even at the time, Pettus was notable for his age. The Washington Post noted that civil service reforms that would institute a mandatory retirement age would have, if extended to the Senate, have returned the 84-year-old Pettus to civilian life, along with many of his colleagues.5 In 1906, when he was 85, Alabama Democrats genteely decided to re-elect both him and Morgan—but held a primary to select “alternate” senators, who would take their place in the upper chamber should one or both of them die during their term.6)

Pettus was popular. He was well bred. He was friendly. So why rank him among the members of the Bad Congress?

Hamlet, seemingly in a fit of madness, proclaims “That one may smile, and smile, and be a villain.” Despite being practically the definition of senatorial, Pettus was a villain.

The telling of history reduces to a series of caricatures: Lincoln freeing the slaves, FDR ending the Depression, Nixon ruining trust. Such caricatures not only distort but they occlude. For any major historical movement, the figureheads represent not their idiosyncrasies but rather the harnessed energies of legions of people of the second, and third, and Nth ranks.

Pettus is not famous, although the bridge that bears his name became a flashpoint of the Civil Rights Movement. But without him and people like him, the project of whitewashing the betrayal of the Civil War would have failed. It is easy to condemn brutes like Pitchfork Ben Tillman. It is harder to see that those like Pettus are the more influential and the more sinister despite their more attractive personalities.

Pettus was a foot soldier, or maybe even a platoon leader, in the fight to re-establish white supremacy. (Despite encomiums for his independence of mind, incidentally, Voteview suggests that Pettus was a dead-average Democrat.7) The old Confederate general triumphed in that conflict. While Pettus was in office, Alabama passed its 1901 Constitution , which codified both white supremacy and the exclusion of the poor from office—the result not only of the desires of Alabama’s powerful interests to enact such a document but of the steady withdrawal of the federal government from the protection of state populations from the tyranny of local oligarchs.

Laments that he was the last of the old-school Southerners only proved that his cause triumphed. The assumption that the old ways had disappeared made it easier to create a replacement order. Slavery may have been ended, but Pettus and his generation created the architecture of an anti-civil rights movement. That earns him election to Bad Congress.

Hartford Courant, “Senator Pettus Dead: Alabama Statesman Dies of Apoplexy at Age of 80.” July 29, 1907, p. 13.

New York Times, “Senator Pettus Dies, Aged 86 Years”, July 28, 1907, p. 7.

Savoyard. “Edmund Winston Pettus”. The Washington Post, August 4, 1970, p. E10.

Boston Globe, “Dies at Hot Springs”, July 28, 1907, p. 10.

Washington Post, “Age Makes a Difference When Some Are Concerned”, March 10, 1906, p. 9.

Washington Post, “Alabamans Choosing ‘Alternate’ Senators”, August 26, 1906, p. E1.

There’s going to be a footnote later but Voteview is messing up right now.