I’m Paul Musgrave, a political scientist and writer. This is Systematic Hatreds, my newsletter about my thoughts regarding politics and how we study it. The newsletter takes its title from a line in The Education of Henry Adams:

Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, had always been the systematic organization of hatreds.

This week, while I recover my writing schedule, we’re overthinking procedural television. Think of this as the amuse-bouche while I prepare tastier meals for you later.

Copaganda Goes Global

We all have our pop culture indulgences, and mine for many years was Dick Wolf’s Law & Order, particularly any season with Sam Waterston as Executive Assistant District Attorney Jack McCoy. (John Mulaney’s line about missing Lennie Briscoe, played by the deceased Jerry Orbach, more than departed members of his extended family is uncomfortably literally true for me.)

Law & Order bootlegs and DVDs were a frequent, undemanding accompaniment for me in graduate school, a time when a combination of weak coding skills and unreliable citation software meant that I had not yet automated away the sorts of tasks you can perform with procedural television playing in the background. Over the past undisclosed number of years, Law & Order went off the air, eclipsed by its immortal spinoff Law & Order: SVU, and Dick Wolf cemented his hold on non-demo audiences with the NBC Chicago franchises and the CBS FBI franchise. By that point, my television tastes had moved well upmarket, and so I’d lost track of his oeuvre.

Until a week ago, when, having temporarily drained all the content I was interested in on several different platforms, I watched four episodes of FBI: International, a spinoff of the shockingly popular (to me) FBI franchise helmed by Derek Haas but generally run as the Dick Wolf procedural that it is. (Full disclosure: I was going to watch Seal Team because it was higher on Paramount+’s recommended list for me, but it turns out to be boring—and sure also jingoistic and whatever but mostly dull.)

So FBI:International it was. Unfortunately, as the author of the world’s leading scholarly article on Tom Clancy, this proved to be a mistake, because all I could see was how the show—and its gaps—present the world to Americans. A combination of the limits of the copaganda narrative, American chauvinism, and the political economy of globalized entertainment means that the show ultimately fails even as television you can watch with the coding window open.

The show’s premise is that the U.S. government has a special “fly team” of FBI agents stationed in Budapest who are available to help advance U.S. interests and protect American citizens in international trouble. (Given the scope of U.S. government, I’m surprised to learn that this is entirely fictional.) With the aid of its Europol liaison (Europol being another one of those agencies whose importance can be inflated for narrative purposes), the team assists in solving a problem of the week in a different European city (or Hungarian street dressed up to serve as a different city).

This could have been a marginally interesting show. Imagine: FBI agents solving crimes in Europe, where they can’t count on local cops, they’re always present as a guest of the host government, and they have to use wits rather than technological sophistication (and armament) to succeed. Given that the modern template for a cop show is some hybrid of NCIS, CSI, and SWAT, radically reducing the comically overpowered American justice system could have made for great television.

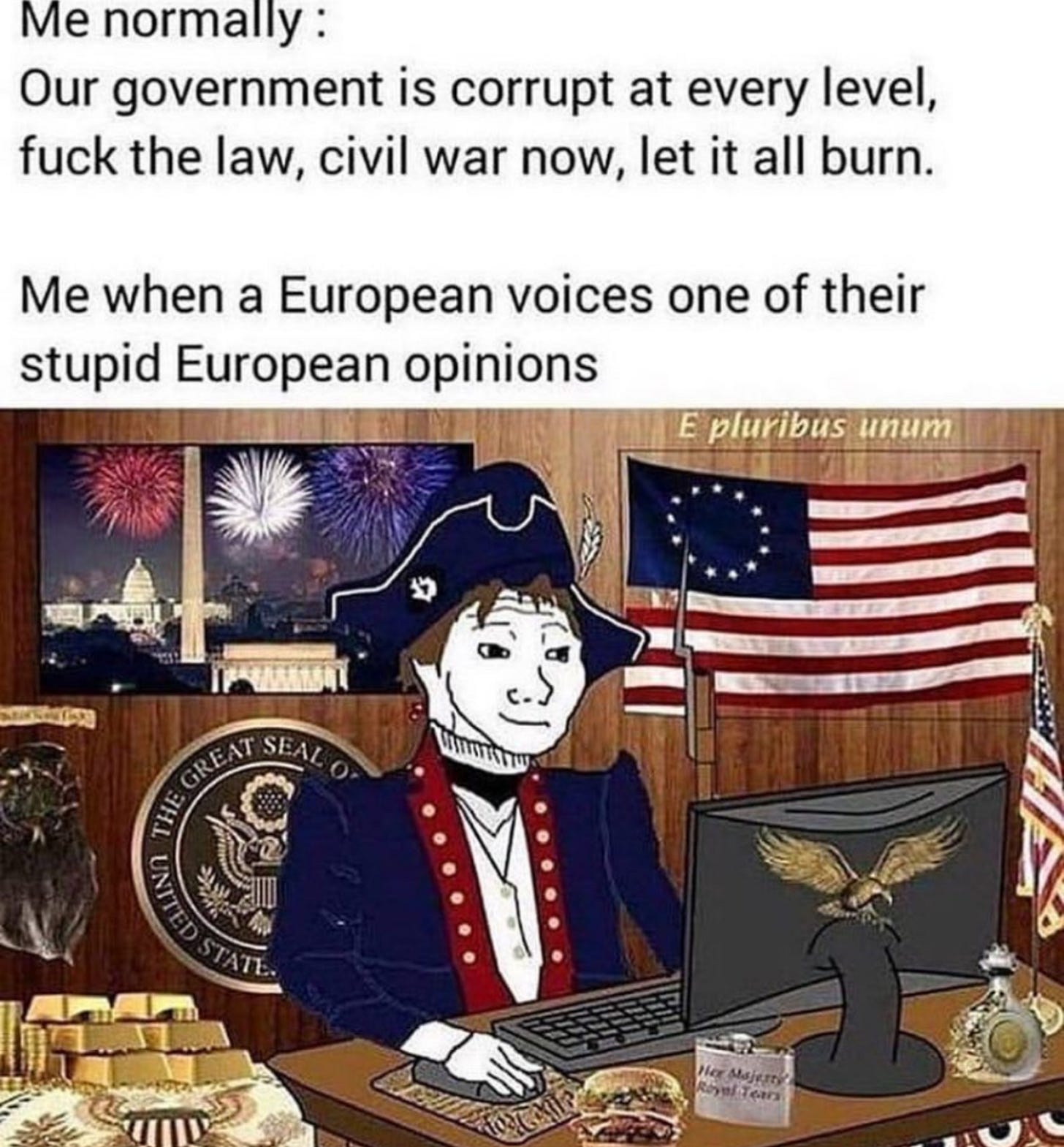

The other great source of tension could have been cultural conflicts. Like a great many Americans who have spent time abroad, I oscillate between criticism of my home country informed by my (rather privileged) time abroad and absurdly exaggerated rebuttals of even fair-minded European criticisms of the States—basically thisold meme in real life:

A team of FBI agents living overseas permanently would, one would think, offer a great way to contrast American and European views on everything, from capital punishment to the importance of ice in drinks to whether the United States is objectively the best country on Earth. Imagine, if you will, an FBI agent named “Tex” assigned to the fly team who thinks that socialized medicine makes you weak and France is a bunch of cheese-eating surrender monkeys. Imagine, in other words, a cast of FBI agents with at least some of them having the political opinions you’d expect of an agency that has never had a Democrat as its agency head. (Really.)

Or imagine, as would also seem likely, that a fly team (every time I write that phrase, I think of a troupe of Solid Gold dancers) would be kind of a career-killing move. You aren’t busting bank robbers, narcos, or terrorists—you’re helping individual Amcits who have gotten themselves into bad situations. Interesting work in cool cities, but not the sort of thing that helps you become Special Agent-in-Charge in a real place.

But maybe, for personal reasons (love, a fondness for walkable cities, favorable exchange rates) or professional ones (being exiled because you revealed violations of a defendant’s civil rights, perhaps?), that sort of career dead-end would prove appealing. In a copaganda extended universe full of ridiculously idealized crime-solving gunners, having stories about people who wanted to make a small, positive dent in the universe even though there’s no professional ladder to climb could have been great. (Paramount+, if you’re listening, I have a pitch for a Star Trek show centered on the dead-end “planet of galactic peace”!)

Alas, none of that will happen. For one, cop shows frequently have a close relationship with the authorities, and Wolf seems to be no exception. Since the days of J. Edgar Hoover, as Washington Post writer Alyssa Rosenberg pointed out, copaganda has been favorable to cops, often because of official censorship. In any event, agencies are rather more likely to assist producers who make shows that make them look good—and that kind of assistance has numerous advantages for producers as a result. So there’s no way that the FBI would cooperate with a story about a bunch of washed-up FBI agents, even though any big organization eventually evolves a way to send its malcontents and overly-honest members to a bureaucratic Siberia. For the same reason, it’s unlikely that FBI: International would suggest that FBI agents would look down on civilian FBI employees, even though, as scholars like Bridget Rose Nolan have shown, status games like those are ubiquitous in the intelligence community and elsewhere.

The same reasoning holds for why portraying culture clashes between Americans and Europeans, or even among Americans about Europe, would be unlikely. FBI: International benefits from the generous tax subsidies of the Hungarian government. (Such tax incentives are also key to the American holiday-movie industry, as I reported last year.) Setting aside Hungary’s recent turn toward reactionary politics, which might be a reason to avoid highlighting European politics, anything that could be perceived as critical of Europe would be reasons to yank such subsidies, and hence the show’s business model.

And why not make the show critical of Americans? Why not ask whether European crime-fighting methods have some advantages, or at least contrast different ways of approaching crime? To ask the question is to answer it. FBI: International is a big-market, major-network show (even if it’s only getting rating shares below 1). The mass American market doesn’t and won’t consume material that’s critical of America, and a host of reactionaries toting thin blue line flags stands ready to condemn anything critical about the world’s most carceral democracy as a concession to SJWs. (SJWs, for their part, are neither a large enough audience nor a fit market segment for midcult scripted dramas on CBS.)

For me, the biggest immediate impact of FBI: International’s dull portrayal of globe-trotting crime fighters (and just reflect on how much you have to screw up to make “globe-trotting crime fighters” boring) is that I need to scrape the bottom of another streaming barrel. For U.S. culture, the mutually reinforcing factors that make dramatic, critical depictions of the United States and its role in the world untenable is, ultimately, a much bigger loss.