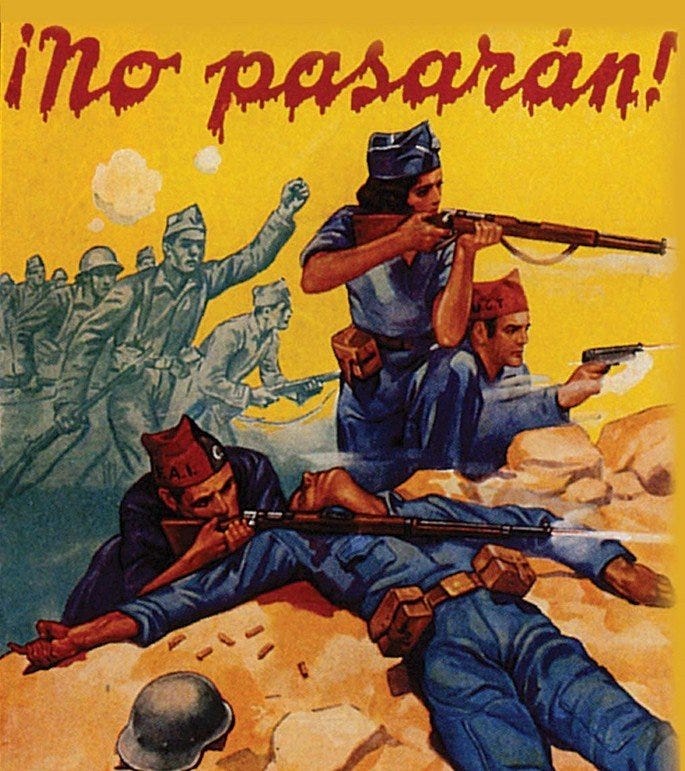

Haunted as I am by the shadow of the short twentieth century (1914-1989), I most often interpret the events of my time by analogy to the events of that era. Consider Ukraine. The Ukraine war has clearly become the Spanish Civil War of our time—radical new ways of war, messy international involvement, and the notable reluctance of the powers of liberalism to fully commit to a struggle viewed as pivotal to others. Watching the proliferation of Ukrainian flags and expressions of solidarity with President Zelenskyy—who deserves those encomiums, and more—puts me in mind of the inspiration that many must have felt in raising funds for the left armies in the Spanish Civil War. As Ginsberg recalled in “To Aunt Rose”:

Aunt Rose—now—might I see you

with your thin face and buck tooth smile and pain

of rheumatism—and a long black heavy shoe

for your bony left leg

limping down the long hall in Newark on the running carpet

past the black grand piano

in the day room

where the parties were

and I sang Spanish loyalist songs

in a high squeaky voice

(hysterical) the committee listening

while you limped around the room

collected the money—

Aunt Honey, Uncle Sam, a stranger with a cloth arm

in his pocket

and huge young bald head

of Abraham Lincoln Brigade

Lines like those make more sense now than before the (2022) invasion of Ukraine. This is how it must have felt to have been so emotionally invested in a faraway struggle, I think. Others have felt this earlier, about other conflicts, but this is the one for me, and this reference is, somehow, the nearest one. (My own ancestry is as distinct from interwar Newark Jewish socialist circles as you can get, but my culture, even my patriotism, derives far more directly from those circles.) To be sure, I’m not standing next to Aunt Rose—all of the solidarity and donation boxing I encounter is a social media phenomenon, such is our fallen post-physical age—but I can feel more clearly the geist of that zeit. In another way, knowing “Aunt Rose” and any number of other cultural productions that touch on the Spanish Civil War also prepared me for this moment, shaping how I experience the present through my exposure to the past.

As a scholar of international relations, I feel the pull of other analogies, these academic rather than cultural or emotive—about how the lessons learned in the Spanish Civil War contributed to specific tactical innovations that would be applied in the larger European war a few years later, for instance, or more generally about how international institutions and customs can be quickly replaced by violence when a crisis of confidence hits. Those precedents, too, shape how I respond to this moment.

History teaches by example and by experience. The examples it serves me now are relentlessly pessimistic. The experiences it furnishes are dispiriting. To admit of despair feels like something that I am not supposed to express, and I do not say that because it lets me follow in the well-worn path of posing as someone who offers secret knowledge to his readers. Rather, it’s because there’s a great deal of tacit and overt pressure on academics and intellectuals to offer hope in trying times—or, rather, not hope so much as solace and practical advice.

For someone of a more optimistic frame of mind, these pressures can manifest in crafting concrete arguments about historical precedents to both illustrate the dangers of actions and to hold out the promise that, say, calling one’s congressperson will thwart the destruction of entire federal agencies. For some, this can be an extension of service; for a few, and not all opportunistic, it can be lucrative. Such interventions are often justified by the explicit or implicit promise that the study of the past will illuminate our understanding of the present—and enhance our confidence in our actions. This shades too easily into a promise that understanding how some event X turned out will boost our confidence that event Y will follow the same script. It’s in those moments that one sees the ranks of reply guys rally to the call, newly secure in the knowledge that history is on their side. It is tempting to mark the end of the Spanish Civil War with Franco’s death and the establishment of contemporary liberal Spain and then to point to that as a marker of the eventual triumph of one’s hopes. Certainly, those are the sorts of stories that sell best. And they may also be the most effective, because without faith or at least hope there is no reason to endure—and if there is no reason to endure, there is no chance of deliverance.

Nevertheless, the shadows of the past cloud my ability to conjure boundless optimism in the face of what is already here. The value of the study of history is not to supply comforting precedent for action in the present. The past is not a warehouse of happy morality stories, of just rewards for virtue and vice. Most histories are not comforting. Empires fall. Cities burn. People die brutally and unjustly. Even more are forgotten. The process of turning the past into history too quickly jumps over the experiences of how it felt to experience it. Those omissions can lead one to expect history to unfold as a series of easily anticipated chapter titles and clear lessons, rather than something that presents itself as a daily trudge with the patterns most often visible in hindsight. Living, suddenly, in history makes one appreciate the long periods only gestured at in writing that had to be lived by those who did not know they were in Chapter 6 of some textbook. It’s easy to write cheerfully of a distant society spending a few decades under autocracy and another thing to contemplate the prospect that the remainder of one’s own life will be enclosed by the grim bars of a hostile polity. (Here, I should note again one of my favorite books, a life-changing volume I read in Shanghai twenty years ago: 1587, A Year of No Significance by Ray Huang.)

Nor does exposure to history as a scholar allow one to view history cheerfully, as a source of prospective vindication, as it is often implied to be by those who rage against their enemies that history will judge you. Next to “historian here!”, the most annoying invocation of history in online discourse is the confident assertion that someone is on the wrong side of history. History will judge, but why should we assume it will judge fairly? It is all too easy to conjure examples of history serving as a hanging judge, eager to condemn the guilty and the innocent alike so long as those in the dock opposed those in power. Indeed, writing those sorts of histories is one of the few ways to make a good living as a historian. Bill O’Reilly puts his name on a lot of those kinds of books, and they sell very well. One day, he will write a book called Killing Woke to tell the story of our age.

These sorts of popular interventions also only work if we tamp down of the ceaseless doubt and scrutiny that scholarship is usually held to require. hard to know exactly what makes a particular side of history the wrong side. Was the tsar on the wrong side of history because he was the product of a reactionary institution swept away by an inevitable revolutionary tide, or was he on the wrong side of history because he lost a struggle that might have been won with more adroitness or better luck? To the extent history takes sides, it takes an incredible amount of faith to believe it will ultimately take your side. That is why I ultimately think that invocations of history as judge are more about faith—they should be understood as appeals to Clio, a deity, rather than to any actual human historians of the future. As prayers those words make more sense than as arguments.

Does that mean that history offers nothing of value to us now? No, the value of the study of history for action in the present is to offer a reminder that we are not alone in our struggles—and to remind us that the resolution of our struggles will play out differently than we imagine. The past decade has presented me with real-world analogues I had lacked that have changed how I interpret the Age of Jackson—Jackson as J6er, Henry Clay as resistance lib!; how I understand the Reconstruction Era and the backsliding that followed (that history, indeed, offers almost a checklist of how to build an exclusionary legal regime in a nominal democracy); and, now, how I understand the violent oscillations of the era between the World Wars. I mean that I understand these periods better now both as a human who seeks to empathize with the experiences of my temporally distant fellows and as a scholar who seeks to recover the intangibles, the exuberances and depressions, of earlier eras to better understand my own.

These experiences and how they have reshaped my understanding of what I’d known, limply, from books have made the stakes of the moment clearer to me. My operating assumption is that we are living in a time that will be remembered, regardless of who wins, as a period between World Wars. More precisely, this is an era of a dramatic reconfiguration and we are only at the beginning of it. The typical tools of those periods—population transfer, performative violence, the erasure of old sovereignties and the entrenchment of new regimes—are on offer. Fundamentally, the choices on offer are narrowing to the prospect of a new world war or the grumbling resignation of free societies to the global dominance of a combination of oligarchical capitalism and simple kleptocratic plundering. It did not have to be this way, but this is how it is.

Expertise offers little satisfaction. I would prefer not to know what is likely to come; I would prefer to be able to be taken by surprise rather than to view the future as likely to be a performance of a tragedy I will have rehearsed a hundred times in advance. I know, for instance, that the policy of the United States will play a major role in tipping the balance toward instability. Before the First and especially the Second World War, U.S. unwillingness to play a constructive role in asserting and maintaining a balance contributed to calamity; now, it is the declared policy of the United States to promote instability and—astonishingly—the division of the globe into great-power spheres of influence to palliate not just a rising power but a falling one. My intellect is fascinated by how political uncertainty translates into drives for security or revolt, and it has a front-row seat as it watches my emotions process uncertainty into reactions. There are unlikely to be strong enough reactions in the short term to shock the administration back onto a cooperative course. One can know all this and still take little satisfaction other than the thin victories of seeing one’s pessimisms manifested.

Where, then, are we to take our comfort, our hope, our energy to endure? Appeals to external authority or to precedent will not save us, so we will have to save ourselves. For those of us who grew up believing we were on the right side of history—post-historical, even—it is time to embrace new ways of defining ourselves. Instead of ascribing agency to vast external forces, it is time to find agency within ourselves despite the unpropitious circumstances. We must find our hopes and solaces in the radical embrace of the present and the stubborn transmission of what is best. The present matters, no matter what the past says.

"Living, suddenly, in history makes one appreciate the long periods only gestured at in writing that had to be lived by those who did not know they were in Chapter 6 of some textbook."

Just one of a string of thoughtful reflections on the moment. I think most people have understood their lives as narratives for many millennia, and it has often struck me as very sad when I encounter in reading about the past people who I know died seeing a personal narrative end in the midst of a political narrative heading into darkness. Although my mood is as dark as this post, I don't think we yet know whether the current moment is going to turn into an era. The odds are not promising, but there are still many possibilities, which is why I'm still reading the news. But as someone who grew up in the rising arc of postwar triumphalism it does feel now that the progressive (in the old sense) narrative surrounding my own life is being revealed as an "interwar" mirage in the midst of a cosmic dynamic of inverted dialectic, where opposing forces never reach a new synthesis, only a pause between ongoing struggles that sing the same song in increasingly strident keys.

But because today's narrative isn't yet determined, and we don't know that we are beyond the point where well executed agency is no longer possible for those hoping to reverse its direction, it would be best not to invest overmuch in lessons not yet fully validated. The lesson of the Lincoln Brigade I found most pithy when I was young was taught by a comic songwriter, Tom Lehrer: "They won all of the battles, but we had all the good songs!" Looking around right now I see lots of people singing the good old songs, but I also see people (or pixels representing their ideas) trying to figure out different tactics that can win battles on unfavorable ground and trip up the momentum of a narrative turn that's only six weeks along.

If I may give a quick argument for synthesis of past and present, I do think there are some powerful tools, typically in the conservative playbook, in the past to support the transmission of what is best.

Alan Jacobs' term for "empathize[ing] with the experiences of my temporally distant fellows" is to break bread with the dead. (Two key caveats: I've read his essays, but not the book of that name, and his version is certainly grounded in religion). But I think remembering the past as full of people, some who fought and won for what we hope to preserve, even more that lost, and multitudes who managed no more than to keep the flame alive. But I think there is something to be said for reading of their lives and writings, in conversation with others in the present as well. We may not take hope from this but there can be valuable perspective.

I also think the recurring liberal drive for a useable history, to find ways to try to build an actual solid majority, not from those with busts of Caesar or Stonewall Jackson but that look to Washington or Lincoln even with all their problems and failings, let alone any number of marginalized at the time that were more prophetic figures of what we hope to now transmit.

Conserving and repairing is not sufficient, we will need what is new. But what is good in the present is often based in wobbly social compacts of the past, full of weaknesses and at times obsolete. But I think it is a worthy effort to look for flawed figures of the past who nonetheless helped build or transmit what is best or honorably failed in that task. Acknowledging and offering some grace for those flaws can help in doing the same our fellows in the present whose support we will need to have a chance of success and offers a potential common language and set of values to build off of.

I think a weakness of present progressivism is to see history as more of force and in a way that seeks to wash our hands of the origins of what we might hope to preserve. There are better alternatives than whitewashing that past and potential strength in bonds grounded in truth and acknowledgment of both good and bad.