Forever young

I want to be forever young

Do you really want to live forever?— “Forever Young”, Alphaville

We take a lot of things for granted. Among them: that childhood and adolescence don’t really change. Our parents might not have had calculators in math class and our children might have Chromebooks in class, but some things are universal. As a professor, I try to find some common ground with my students, but try as I might it keeps getting harder.

“Ah,” you say, “it was ever thus.” Nope. Not at all. Things that were relatively constant for a long time have changed really fast in generational terms. I think this matters for those of us in youth-facing industries, and I think it’s a good time for us to mark our beliefs to market.

Television’s dead

Let’s take the obvious point: media consumption. As part of a senior thesis this year, I had to explain how network television worked in the three (well, four) network era worked, from commissioning pilots to the TV grids in the newspapers to the notion of summer re-runs. It felt like explaining the finer points of cuneiform.

The entire gestalt of old-fashioned media is foreign to today’s yutes. In the Nineties, when I was a teenager, the top-rated television show would routinely have about a fifth of televisions tuned to it—more than a third during Seinfeld’s final season. In the late 2010s, when my students were the same age, it was more like an eighth or a tenth—and I’m pretty sure the demographics of viewers for NCIS skewed a little older than ER and Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?. In its place: streaming and social media, including the hegemonic TikTok. (My student tried to explain how TikTok worked; I am a worse pupil than teacher.)

I mention this because television used to be a gravitational constant. Even though we all know that it doesn’t work like it used to, the old rules are still second nature to people my age and older. It’s just an expectation that everyone would know this, the same way that everyone knows how an answering machine worked. (Wait.) Again, if you’re tempted to say, “ah, the young have always been different”—folks, this is television. From 1990 to … 2005? … this was the central medium in American life. And i works so differently now as to be unrecognizable. This is more like the transition from the first half of the twentieth century to the second half. And it touches a lot—including the fact that there’s very little intergenerational commonality in cultural consumption. It turns out the monoculture was great for building little touchstones of cultural commonalities.

Many fewer teens have jobs

Other differences are arguably just as fundamental and less visible. The death of broadcast TV affected us all. The death (or at least dormission) of the teen job, by contrast, has been harder to track. When I graduated high school, about 45 percent of 16-19 year olds worked, a number that was broadly in line with what it had been for half a century before. After I graduated, that number plummeted to just over 35 percent—and then the 2008 recession led it to crater still further, reaching a low of 25 percent. (It’s now back up to just below 35 percent again.)

What’s behind this? One explanation has to do with increased demand for education. A Brookings report sees increased school participation as the driver, for example. Others point to increased competition for college admissions. But these fail the interocular test: dips in labor force participation match up perfectly with recessions. The simpler story is that teens are less productive, less attached workers and so they’re the first to be axed when the economy dips. Of course, this has long term repercussions, since if you arrive in your twenties without work experience you’re less likely to get a job—work experience matters a lot for subsequent employability and for remaining employed. (This also suggests that a lot of anti-Millennial stuff in the 2010s reflected the fact that earlier generations broke the economy, including the implicit job-training programs that entry-level jobs provide.)

Fewer teens drive

For generations, reaching 16 meant a sprint to get a driver’s license. That’s no longer the case. The U.S. Federal Highway Administration tracks the number of drivers’ licenses by age, and their stats show a decline in the number of teenagers (here, 18 year olds) with a license. (2008—a very important year!—is shaded.)

Why? As with teen employment, there’s a lot of stories out there—including the appeal of cell phones keeping teens in the passenger seat and the worry of parents keeping teens from the driver’s seat. But sometimes one chart tells a story—2008 broke a lot about the economy. I suspect here that it’s not just a general recession-induced decline in demand but also the post-recession increase in used-car prices and the decline in employment reducing the supply of drivers. (Cash for Clunkers probably contributed to the decline in teen driving!)

Fewer teens have sex

Teenage sexual behavior has long been a bugbear of culture wars, but things have changed so rapidly that it’s telling that our debates are now about sexual identity rather than sexual behavior. The CDC tracks a variety of risky youth behaviors, including survey questions about teenage sexual behavior, and their statistics show a major decline in the percentage of high school students who have ever had sexual intercourse.

What’s behind this? Again, lots of stories, although a Scientific American interview suggests that everyone is having less sex—and a lot of the sex they’re having is now, to be blunt, porn-influenced, which may be scaring people out of intimacy. (Hey, there’s no neat 2008 story here!) Regardless, this is another pretty big milestone of development that’s being delayed relative to other living generations’ experience.

Fewer teens fight

Beyond the “puriteen” observation, there’s also the less-noticed fact that today’s teens brawl less—a lot less. (This is one of the data points that made me wonder whether my generation wasn’t a bunch of lead-poisoned primitives.) The data again comes from the CDC.

I’m less sure about what’s going on here, but…this does look more like the fabled 2012 cell phone effect than our other charts. It could be that impulsive behavior is being funneled into other directions.

Many more teens wear seat belts

Another point for the lead-poisoned primitives take: today’s teens wear seat belts, while teens in my generation and earlier apparently didn’t.

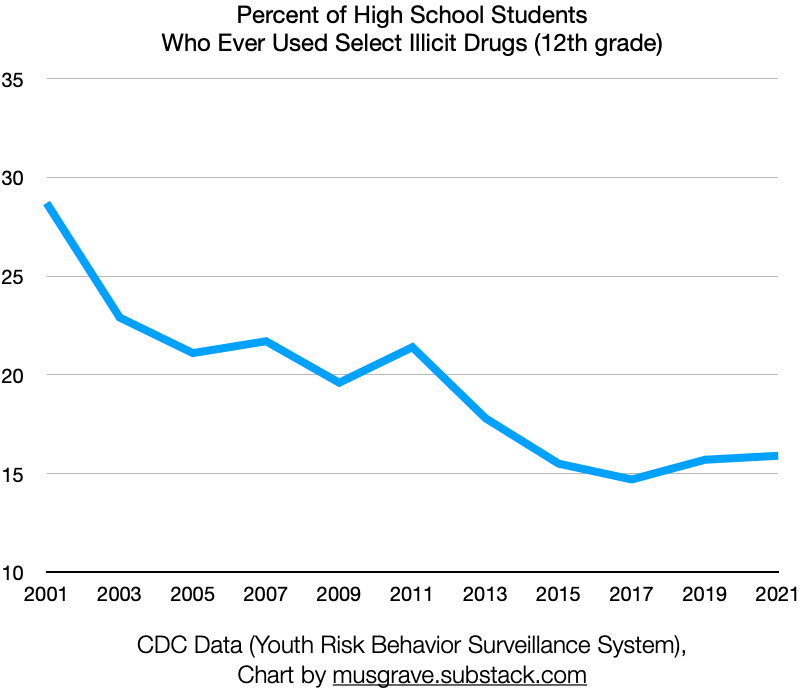

Many fewer teens drink and do drugs

The hits keep on coming for my generation. Today’s teens do fewer drugs and drink a lot less than earlier generations. Like, a lot less—a whole bunch of students must arrive at college without ever having had a drink! This is, again, a major shift, and one that may reflect a number of factors (if you can’t drive, you can’t party as easily?), but it shows a number of milestones being pushed back further and further.

Many fewer teens drink soda (!)

One statistic that puzzles me: the yutes don’t drink pop anymore. Soda was omnipresent in my teenage years. Billy Joel celebrated the cola wars. The Boomers were the Pepsi Generation! And today—teenagers don’t drink soda.

(What do they drink instead? Energy drinks—Monster, mostly.)

Fewer teens rest properly

Another statistic that I think most clearly shows the influence of screen time: teens aren’t sleeping. They’ve rarely gotten enough sleep, but we’re now talking about something like a 30 percent drop in the number of twelfth-graders getting eight hours. That’s…not great!

Conclusion (For Now)

The point here is not to berate or celebrate anyone. I’m simply and sincerely interested in learning what’s changed. And the answer is — a lot. My teenage experiences weren’t representative of my generation, but they’re an even worse guide to Gen Z. If you’re a marketer, you probably know this—but if you’re an instructor, you probably don’t. We all need to retool to think about baseline shared expectations.

Much as with Clinton's incorporation of much of Reagan's policy program, the most interesting thing about these shifts is that neither cultural conservatives nor communalist liberals seem especially happy about or interested in these changes. There's a whole set of public intellectuals that you think would want to stage a victory parade (well, maybe some of them are too elderly to march in it) but rather as with global population growth, the people who went all-in on the menace of youth sexuality or drinking or watching too much TV or delinquency can't afford to acknowledge any change that didn't come from strong public controls or compulsion. It's enough to make one suspect that they didn't particularly care about behavior as such, but only about the usefulness of arguing that a menace to the yutes justified the harsher use of juridical, regulatory or civic compulsion elsewhere.

great insights and very informative! thanks!