The politics of shifting baselines

I’m Paul Musgrave, a political scientist and writer. This is Systematic Hatreds, my newsletter about my thoughts regarding politics and the study of politics. The newsletter takes its title from a line in The Education of Henry Adams:

Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, had always been the systematic organization of hatreds.

This week, we’re talking about the concept of shifting baselines and how what you’re accustomed to determines the problems you see.

The politics of shifting baselines

Susan Kirsch is a homeowner. Like many people who bought their home, Susan likes things in her neighborhood the way they are now. And like many people who own their own home and have a bit of an activist streak, Susan is willing to show up to meeting after hearing after gathering to make sure that her home stays the same.

If you’ve been on Twitter or the New York Times recently, you’ve read about Susan: the Marin County retired teacher who’s successfully blocked dozens of people from following her path to homeownership. And if you pay attention to the scholarship on the issue, or if you’ve just ever been to local government meetings, you know that Susan is not alone. As the political scientists Katherine Einstein, Maxwell Palmer, and David Glick have found, there are lots of older homeowners who are willing to invest their time and effort to blocking people who are younger from becoming homeowners themselves.

This post, though, isn’t about NIMBY or YIMBY dynamics, and it’s not even about the politics of homeownership. It’s about something different: the notion of “shifting baselines” and how people can remain anchored in the past. That idea, I believe, explains a lot of the generational discord—why Boomers and Zoomers don’t seem to exist in the same world, even when you try to adjust for the fact that the Boomers are pretty rich and every other generation is, well, not.

The idea of “shifting baselines” comes from a slightly unusual place: Trends in Ecology and Evolution, a journal focusing on environmental issues, where the scientist Daniel Pauly introduced the term in a brief (one page!) but hugely influential (2700+ Google Scholar citations!) article back in 1995.

Pauly sought a solution to the fact that it was hard to get traction on policies to preserve fisheries, even though fisheries scientists were convinced that the collapse of fisheries was a huge issue. After all, in historical records of fisheries, one encountered descriptions of fish abundance that seemed plainly impossible—like nets being tangled by masses of bluefin tuna (an endangered species now) as recently as the 1920s. Other records from the South Pacific and the Canadian Atlantic Coast similarly pointed to abundance of fish decades before that would have seemed impossible even to fisheries scientists who believed that stocks were collapsing.

The problem, Pauly believed, was that fisheries scientists didn’t have a long enough historical sense of what prior eras’ fish stocks looked like to actually and convincingly relate how dire the crisis was. As he wrote:

Essentially, [shifting baseline syndrome] has arisen because each generation of fisheries scientists accepts as a baseline the stock size and species composition that occurred at the beginning of the careers, and uses this to evaluate changes. When the next generation starts its career, the stocks have further declined, but it is the stocks at that time that serve as a new baseline. The result obviously is a gradual shift of the baseline, a gradual accommodation of the creeping disappearance of resource species, and inappropriate reference points for evaluating economic losses resulting from overfishing, or for identifying targets for rehabilitation measures.

If you grew up as a fisherman who could catch a few hundred pounds’ worth of fish per day, then seeing that catch decline to a couple of hundred pounds per day seems like a challenge but not a catastrophe. Yet if the true baseline was your grandfather’s daily catch of a thousand pounds a day, the scale of what’s happened has become much easier to appreciate—yet you, yourself, cannot really emotionally grasp this because your reference points are, as Pauly says, “inappropriate”. And so you don’t act like you’re in the last scene in a horror movie but like you’re in the middle passage of a relatively gradual progress. When your son takes up the trade in turn, he will accustom himself to a few dozen pounds as the daily quota, and so on until suddenly there’s nothing left to save.

The idea, in other words, is that your idea of normal comes at least in part from your own experiences. Whether you think we’re in a crisis or not is not going to depend on some objective state of the world but in the subjective way you process things that are taking place Out There. This, I think, is the sort of concept that once you see it you can’t unsee.

One of my hobbyhorses is that fisheries (which are often anarchic realms) are underappreciated in international relations, my home discipline. And the number of insights like shifting baselines syndrome that we can take back from the study of these realms into other areas of study is huge.

Shifting baselines syndrome becomes apparent as a more general state of human affairs when you start looking for it. One editorial in The Environmentalist gives a flavor:

A good example of this is a possibly apocryphal story that was prevalent in the UK Forestry Commission in the 1990s. The story goes that in the 1950s during the major afforestation of upland Britain with exotic conifers, an area of moorland outside a small Scottish village, was earmarked for planting with North American lodgepole pine. The local inhabitants were not happy and the local newspaper was full of letters of protest complaining that the glorious scenery and dog walking opportunities would be ruined by the planned forest plantation. Needless to say, the plantation was duly established. Forty years later, it became due for harvesting. The local press was full of letters of protest from the nearby residents complaining that the glorious scenery and dog walking opportunities would be ruined by the planned harvesting operation.

This is one occasion where I’m happy to admit that even if the particular story is false, as a general account of a social phenomenon so familiar as to cause deja vu I will accept it as if it is true. As the authors write, the moral is clear: “Human memories are indeed only a generation long.”

Something like shifting baselines syndrome affects how ordinary people, like Susan, and elites, like her senator Dianne Feinstein, approach political question. Nobody treats political questions as de novo; we all approach them under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past, as Marx would say.

But Marx missed that “the past” is not constant for all observers. Susans don’t think of themselves as the baddies: they think of themselves as bold rebels facing down the evil growth machine. Having argued with Susans in the past, I know that one of their contentions is that there’s really no need to build any more housing—everything should just be preserved, and it’s only developers who want more houses. But there’s literally 110 million more people in the United States now than there were in 1980 (when Susan bought her house, more or less)—that’s an increase of just under 50 percent! We need loads more housing, everywhere, and especially near where the jobs are—but that’s a product of being alive in the word and not retired from it.

(One minor note: even if baselines shift with the generations, that doesn’t mean that your sense of contemporary situations can’t be updated—but if you have stopped paying attention or learning, then you’re probably a lost cause, and as people get more settled into their lives, well, they stop paying attention. My favorite new album, for instance, is Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories, which is a decade old.)

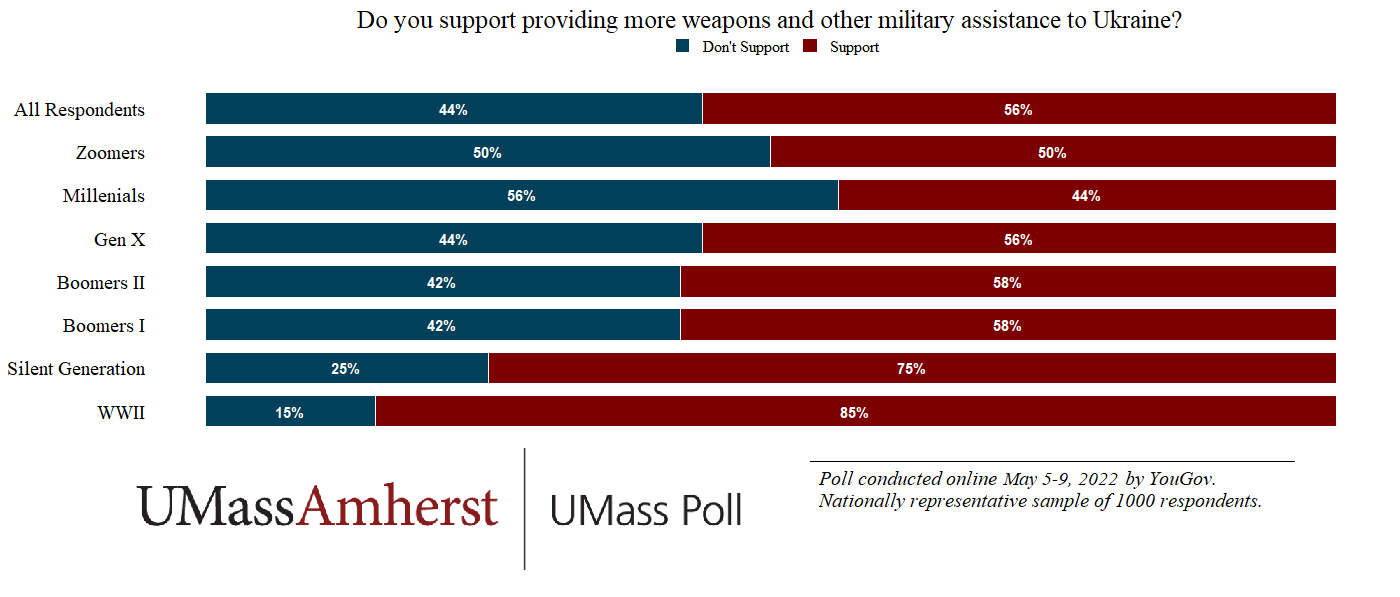

It’s always interesting to think about when your baseline is. I think there’s a good test: Ask yourself what year was 20 years ago and honestly record the first year that comes to mind. For me, the answer is about 1995. (Similarly, it’s hard to remember my actual age without doing any math!) My “past” begins in about 1998 as lived memory and about 1968 for historical centering (I’ve read a lot of Nixon historiography), while the past of my students begins sometime around 2016. When you ask them and me about what we think about how the United States should act toward the Ukraine war, we have rather different opinions:

Obviously, there’s more going on here than generational differences, but if your reference point for “U.S. policy intervention” is Iraq 2003 rather than Iraq 1991, or if you’ve never known the Soviet Union but you have known the slightly less threatening Russian Federation under Putin, you’re going to have a different perspective.

Something similar, I think, occurs in a lot of other areas. My students don’t seem particularly engaged by the threat of nuclear annihilation—certainly not to the point of panicking about them the way that at least some folks did during the 1950s. And yet there’s inarguably more and certainly more usable nuclear weapons around to threaten Americans than there were in ~1955! But nuclear war now is just a background condition, something to which we’ve been habituated, rather than a scary new development.

All of this matters a lot for taking action. Another of my hobbyhorses is that no social institution has an age longer than the time that it’s had to socialize the people who enact it. The U.S. Constitution, in other words, isn’t 235 years old but really only about 35 or 40 years old—maybe older, considering the age of folks like Dianne Feinstein, but hardly the weight of centuries.

If your assumption is that American democracy is hundreds of years old, then it’s hard to think of what could shake it. If you think that it’s instead only a few decades old, then it’s much easier to envision it as subject to change and renegotiation—all the more so once one remembers that contemporary First Amendment jurisprudence, abortion rights, voting rights, and so on really are younger than a bunch of Americans who are still living. For someone born in 1942, much less 1933 like Senator Feinstein, Baker v. Carr may seem like a “new” decision, not a foundation of pretty much anything.

The other trick, of course, is that Pauly’s gambit of using data to supply a new, common baseline can work in very different ways in the political sphere than when we’re talking about fish, something for which there’s an actual physical trend (at least in theory). Social worlds aren’t quite so naturally anchored. If you can create a social environment in which the pre-New Deal Constitution is the baseline—something that looks a lot like the Federalist Society, for instance—then you can get a lot of people energized in returning to that state.

One of my goals for this newsletter is to share ideas and concepts that I find useful for other folks to think with, not always to persuade you to think to the same conclusions that I reach. I hope that this advances that goal.

Well written article Mr. Musgrave. Glad to see you are using your talents. Was led here by the wonderous Mr. Zuckerburg as your mother's name came up as "someone you may know" in my FB feed.. I went down that rabbit hole and arrived here. Glad I did.

Mr.U. (yes, that Mr. U.)