The war is language,

language abused

for Advertisement,

language used

like magic for power on the planet

Black Magic language,

formulas for reality

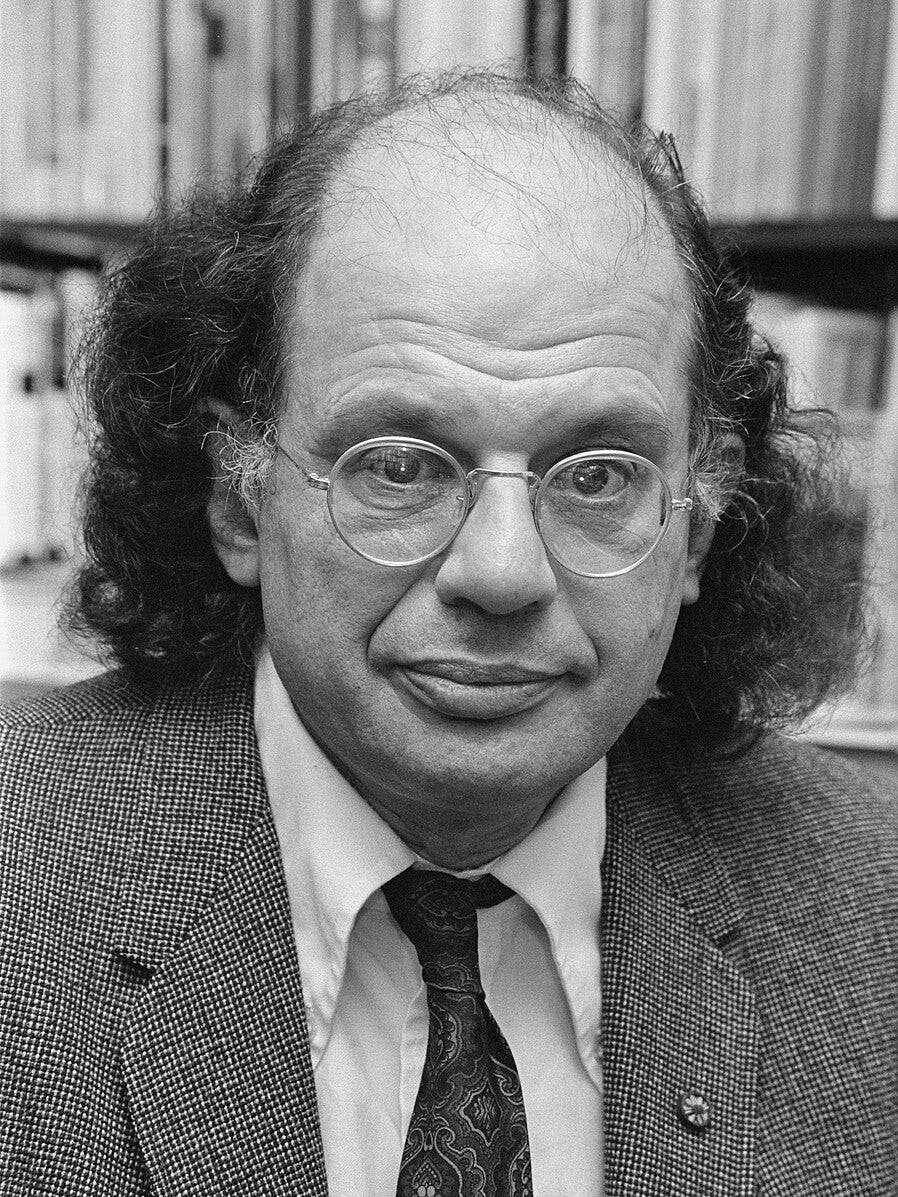

—Allen Ginsberg, “Wichita Vortex Sutra”

Some months ago, I wrote about a poem I teach in World Politics (Intro International Relations): Szymborska’s “Starvation Camp Near Jaslo”. I’m frankly dubious about how much of the poem resonates with the college generation any more, but I encountered it in college and it resonated with me, and its indictment of the reserve that academics consciously, and everyone in practice, brings to thinking about atrocity and loss is meaningful regardless.

But there’s a poem, or rather an excerpt of a poem, that moves me almost as much that I don’t teach: “Wichita Vortex Sutra”, or rather the part excerpted in Philip Glass’s performance of the same name.

This is a fragment, about a third, of the larger poem, which Ginsberg published in 1966 to protest the Vietnam War. “Protest” is too simple; this is no antiwar chant. It is a patchwork of headlines, statements, plays on words, meditations, dictated phrases, and indictments that Ginsberg hammered out driving around Kansas and thinking of Vietnam.

This poem should, by rights, find a place in World Politics or its sister course, U.S. Foreign Policy. It is sophisticated about the politics and the effects of the war. Readers attuned to thinking in terms of interests and bureaucrats will find observations about the motivations and operational codes of Dulles, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson. Readers used to thinking about constructivism and identity will find a rich field of allusions—this is a poem fundamentally about language and how it is used, and deployed, and ruined by war. And those who view the world in terms of human security will recognize the claims made by Ginsberg in drawing together the soft flesh of a Kansas girl and the burn of napalm in Vietnam.

I search for the language

that is also yours—

almost all our language has been taxed by war.

I think, by the way, that Glass’s subtle edit—taking the least Vietnam-centric portion of the poem and focusing on that alone—universalizes it much more. No more headlines or Associated Press snippets; instead, a meditation on spirituality and what it means to be a body in a nuclear age.

I lift my voice aloud,

make Mantra of American language now,

I here declare the end of the War!

Ancient days’ Illusion!—

and pronounce words beginning my own millennium.

Let the States tremble,

let the nation weep,

let Congress legislate its own delight,

let the President execute his own desire—

I don’t teach this poem for several reasons. Some are bluntly practical. I don’t know how to teach this poem to an audience who doesn’t know anything about the Vietnam War, much less the deeper Cold War, or Christianity, or Indian mystics and their reception in the English-language world. Can you imagine explaining the lines

handmedown mandrake terminology

hat never worked in 1956

for grey-domed Dulles,

brooding over at State,

that never worked for Ike who knelt to take

the magic wafer in his mouth

from Dulles’ hand

inside the church in Washington;

Communion of bum magicians

to a crowd who doesn’t have a familiarity with Ike and Dulles and anti-Communism and the Eucharist or the deep meaning of “mandrake”? (Ah, but it’s your job to teach them! No, not at this level; no, not from that far gone a world.)

To be fair, that objection pales a little bit before the fact that, as I mentioned, the Glass excerpt skips those passages—which read a little leaden anyway in our post-trust age. The deeper objection is that it is hard to establish communion about the poem if people aren’t feeling the ability to enter into communion—to be vulnerable, to receive, to drop their defenses. And that is not where a modern classroom sits, if ever a classroom did enjoy that kind of relationship.

When Ginsberg writes about war and politics and language, he also writes about sex and desire and fear. Those are an integral part of his project of making this poem about war’s effect on us all—on how living in the nuclear age reduces our relations to fear, how it poisons our relationships with each other and the stranger, how it leads us to draw a curtain of language to distract us from the reality of state violence conventional and otherwise.

This is profound stuff. It’s a genuine critique of the state system and its effect on compassion and fellow-feeling—and it’s an actual, if sketched, theory of how language works to make the world that prefigures, complements, and (I think you could sustain) goes beyond beyond Carol Cohn’s better-anthologized piece about gender and nuclear war.

I haven’t had the gumption to teach this yet, though, because it would require a trust and mutual vulnerability that the contemporary climate conspires against. And in a large course, those factors are all exacerbated. Perhaps most of all, this is a text you have to sit with and go over a few times—even in the recorded, musical version. The contemporary university is not set up for leisure and contemplation, and those habits, if not cultivated, are hard to summon ex nihilo.

This is probably my failure. There is probably a strategy to bring this work—the poem, and all that besides—into my class. But even the brave can choose the paved road instead of the rough one sometimes.

Failure? Maybe the right course in which to teach this - a small honors seminar, for example - just hasn’t presented itself yet. I don’t see failure in a thoughtful decision to set this aside for another time. I see a good teacher at work.