The Bright Side of the Dark Side

A quick review of Phil Elwood's All the Worst Humans

Books and movies about bad people’s cool crimes face a minor problem. “What Leonardo di Caprio is doing here is wrong,” the text of the Wolf of Wall Street says, while it shows him cavorting with Margot Robbie and millions of dollars. “It’s really harmful and bad. Winners don’t use drugs.” The difference between a text that aims to show how genuinely bad these people are at the core and one that aims to subvert conventional morality by showing how much fun there is to be had in the dark side is a matter, almost literally, of degree.

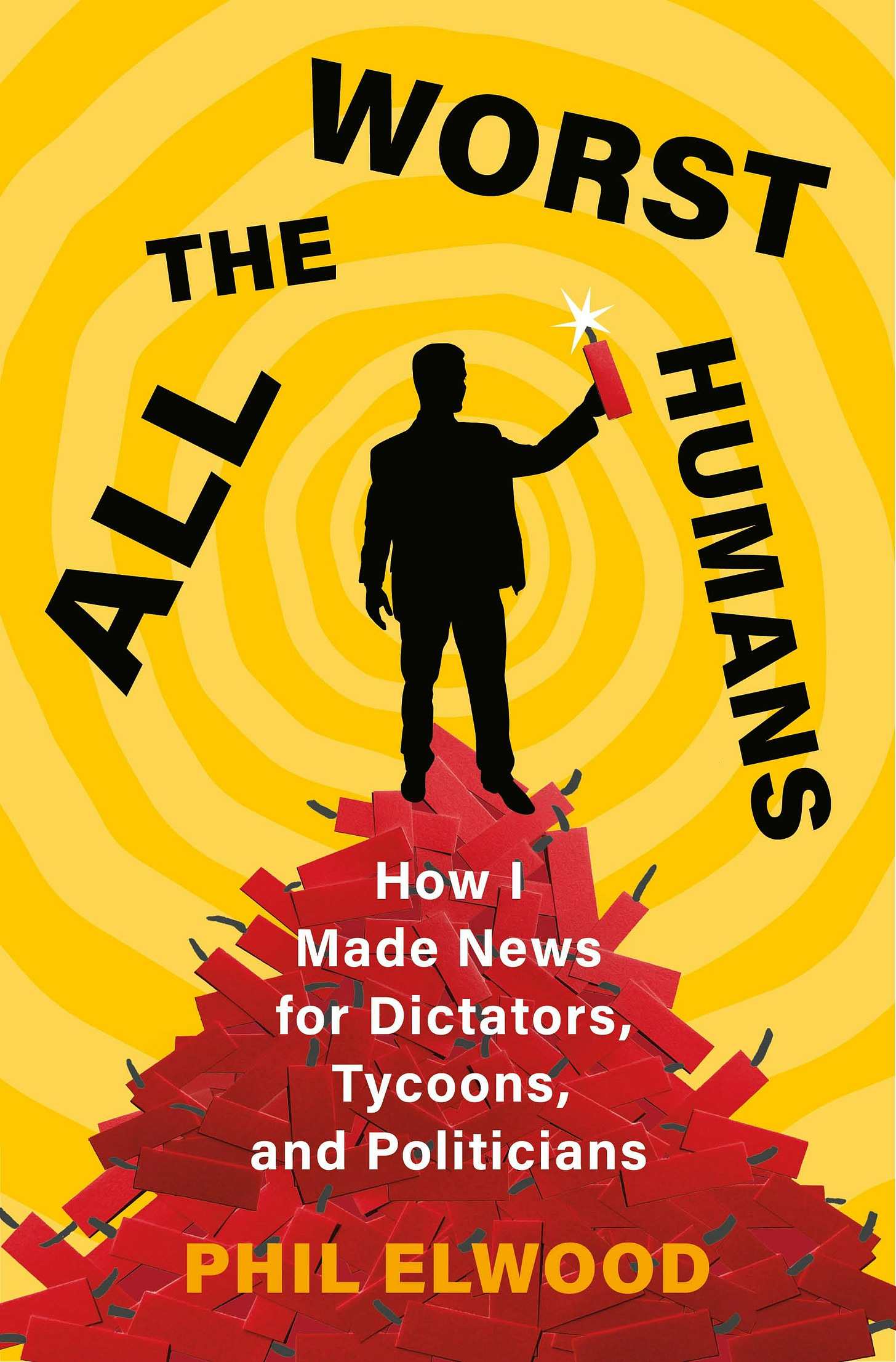

Phil Elwood’s memoir-cum-expose All the Worst Humans: How I Made News for Dictators, Tycoons, and Politicians has the same problem. Elwood describes his life as a public relations specialist, albeit one who worked for, well, all the worst people in the world. According to his telling, of course, he was very good at spinning for governments, frauds, dictators, and worse, until finally his sins became too much for him and he was redeemed by the love of a good woman (and medications).

On the one hand, Elwood wants to convince us that there are bad people out there who take advantage of sweet little democracies. On the other hand, the structure of the narrative has to make plain that it feels really cool to take advantage of unsuspecting publics. Oh, sure, the sinner will be called to repent (and this genre of confessional is, indeed, similar to an altar call or, you know, confession), but the recounting of bad deeds gleefully done does raise the question of which part, exactly, the sinner regrets.

That’s all the more true when the sins being confessed relate to the spinning of stories. The book is enjoyable, and even educational. Elwood is most convincing when he talks about the different niches in the ecology of information spinning. Reporters are in the business of getting information and publishing it first; give them solid stuff, and good stuff, and someone like Elwood can help shape the narrative. It’s important to note that what someone like Elwood gives has to be true, at least from a certain point of view; lie or distort beyond plausibility and you’re burned as a source forever. For someone in the information brokering business, that’s death to your career. Perversely, to twist the truth, you have to be truthful in everything you say—but calculated in what you don’t present, or in what order you do present.

Elwood similarly shows that much of what we take as “the news” is shaped by battles and strategies employed well before someone pushes “publish” in the CMS. Echoing (of all people) Daniel Boorstin’s The Image (and Joris Luyendijk’s People Like Us), Elwood walks readers through how to shape an event for public consumption. The most important part appears to be that nobody does their own homework. If all it takes to show an international audience that the United States isn’t united behind a World Cup bid is one legislator introducing (introducing) a nonbinding resolution, as Elwood claims to have orchestrated, then either that event was a convenient fig leaf for a decision that was already going to be made or the people making the decision had no idea how to evaluate a well-presented bluff.

It’s a fun, zippy read. As a social scientist, though, I couldn’t help but read it through the lens of my profession. This sort of book is informative but not always in the way that their authors intend. For one, of course, we’re only seeing the selective viewpoint given to us by someone who is (or claims to be, but plausibly) skilled in manipulation. For another, even though most stories are told as an obvious triumph of manipulation, that reflects the partial view of the author. By this point, everyone is manipulating everything as much as possible (social media having democratized these techniques)—for every story Elwood shows as a triumph of manipulation, there’s one, two, or a dozen weaponized public relations firms who walk away having failed.

A third point, then, is that pure theory may often be a better guide to what’s really going on than the surface reflections we see in the media. One of Elwood’s clients, for instance, is the Libyan dictator Moammar Khadafy (and no I’m not spell-checking that)—but although manipulation might have some short, or even medium, term benefits, in the long run fundamentals do appear to matter.

Elwood would reply, rightly, that for his clients and the public (and U.S. officials) the world doesn’t exist in the long run, just a never-ending series of short runs. And that’s true! The fourth point, then, is that people like Elwood play an important role in transmitting what the public wants to see happen to people who perform roles on the world stage. What we see in the media, then, is not a strict reporting of the news, but a form of measurement that changes how the news is reported and what the news is in the first place. This is a strange application of the logic of anticipated representation—the idea that actors make choices that comport with what the public would want them to do, even without the public speaking or even knowing what is going on—but I think it is true nevertheless. Elwood and his ilk, squicky though they may be, are the craven tribunals of the public. And if what they bring about is debased, it still, if successful, satisfies the public.

Constructivist thought in international relations has advanced far beyond its 1990s origins, which often seemed disembodied. Books like Elwood’s remind us that the actual agents of socialization—like his firm coaching the Nigerian government on how to respond to the Chibok school kidnapping of dozens of girls—need not be simon-pure activists or free-floating norms. Sometimes, they’re people who teach the right rhetorical formulas, for a fee.