I sometimes wonder how it must have felt to be a professor of physics in, say, the 1920s. You can imagine the excitement for a young gun in the classroom, filled with the latest results about relativity and quantum mechanics and ready to slay the demons of ignorance; you can also imagine the shocks endured by the older faculty, some of whom probably still had æther in their lecture notes, trying to reconcile what they had been teaching with what they were now being told was wrong.

The utmost duty of any instructor, after all, is to pass along what you know to be true. To pass along falsehoods is to betray that trust. But when you find out you’ve been passing along something false that you thought was true—that feels like a deeper betrayal. When the old truths fail, you have to adjust what you’re teaching to what you now know to be true.

Beyond all of the high-minded stuff, there’s also the practical-minded aspect. Dealing with radical upsets to your subject matter also feels like a chore. Damnit, I have to revise Unit 6 again?

I mention this because the past month or so (and the preceding decade) in U.S. politics has had something of this flavor for many political scientists. Indeed, I’ll go ahead and say that everyone who teaches about the subject has felt this way to some degree, and I’ll further extend my point to say that if you haven’t been surprised by anything that’s happened that you have missed something important. Even, say, vulgar Marxists or Chomskyists who believe that corporate interests dictate everything should have been surprised by, say, Fox News calling the 2020 election for Biden, a call whose importance looms all the larger as we learn more about the strategy for delegitimating that election.

In some ways, my arguments in print have been somewhat validated, like the importance of political polarization to undermining the liberal international order (you’ll hear more about that!). But on the other hand there’s tons of places where I’ve been caught up short by Trump, even if I thought that something like that could have happened. To the extent that I’ve been accurate in predicting the uncertainty bars around Trump and Trump’s consequences for U.S. politics, it’s because my frame of reference for the U.S.A. extends well into the nineteenth century, where events like presidents creating their own political parties serve as markers of what is possible under constitutional frameworks that we have long taken for granted.

But plasticity isn’t the same as specificity, and who hasn’t been surprised by the past month? We’ve had a 1912 redux, a soupçon of 1968, a 1974 coda, and now, with a female candidate heading the Democratic ticket, a 2016 remake. And none of these are quite precedents for where we are now (TR wasn’t a major party nominee, LBJ quit during the primaries, Biden hasn’t resigned, and Kamala isn’t a Clinton).

How do we help students make sense of all of this? Here’s my honest dodge: we don’t.

I say it’s an honest dodge because I give the same talk at the beginning of every introductory course. Welcome to World Politics, I say. You might have expected to learn about everything that’s going on in the world right now. That’s the opposite of what we’ll do. Instead, we’ll be learning about important cases in history and key theoretical principles to help you make sense of what could happen.

I spend a whole week establishing this theme. I draw liberally on Samuel Arbesman’s great, readable book The Half-Life of Facts, which documents how long facts remain valid. When I started in elementary school, I tell the students, the map of the world looked like this

and by the time I was finishing high school, it looked like this

The moral is clear: loading up on facts may seem like it’s a good deal, but in the long run you’re better off loading up on concepts and general skills.

I know two folks who were finishing degrees in Soviet studies and graduated in 1992. Sometimes, your degree can see its relevance vanish really fast.

This is a common issue with teaching practical skills. The more specialized your skills are, the more immediately valuable they are—and the more at risk you are that their value can vanish overnight. The same problem applies to learning about the specifics of how a given institution works. At a micro level, an agency or firm might want graduates who know exactly how to fit into their existing processes—but from the outside, there’s the problem of trying to train students for thousands of firms and agencies, which isn’t really feasible, and the fact that every one of those firms and agencies will see some policy or function change in important ways.

That’s when I turn to another, different reading: Borges’s “On Exactitude in Science”, a reading which is short but deep. Building an ever more precise map of the world that corresponds to exactly what’s out there, it turns out, isn’t useful—what we need from our maps is exactly the ability to usefully abstract away what you need to understand and present those relationships in a meaningful way even with a loss of particularity. Understanding how to solve a problem often means understanding how to recognize what kind of problem it is and then to discard irrelevant observations.

In political science, then, undergraduates who want valuable skills need to get something different in the classroom than they would in a job experience scheme. Internships and work experience can help fit new graduates for their workplaces much better than the classrooms. (Although you can take this too far. At one position I’ve held, I’ve heard colleagues who have apparently never worked outside of academia veto the idea of teaching students how to use the Microsoft Office suite on the grounds that Office might go away. After thirty years, and with the likeliest successor being practically a clone, I think we can probably assume that Office is a basic white-collar workforce skill—and it’s also one where learning how to use a tool can bypass a lot of frustrations immediately.)

Teaching higher-level thinking and more abstract approaches to teamwork and analysis is much easier said than done. Classroom work has tremendous value precisely because it’s a way to work out the hidden laws that generate behavior and conflict in recurrent patterns, just as experiences at the coalface teach you how to adapt and thrive when you’re in the thick of conflicts and drudgery.

What the Trump era has shown us, and I include the past month of volatility in this, is that “higher level” analysis is genuinely fundamental. It’s not about teaching the folk wisdom of Capitol Hill or some selected well-known incidents in history; it’s really about guiding people to understand the relationship between the routine and the exceptional, and how both relate to conflict, cooperation, and abstentionism.

If you walked into the past year of political conflict with only a knowledge of the standard playbook of American politics, for instance, you would have been mostly at a loss to explain

the demise of one speaker of the house and his replacement by the third or fourth choice of the caucus

the hostage-taking of Senator Tuberville over military promotions and abortions

the hold-up of Ukraine and Israel aid as part of brinksmanship between the White House and the Republicans in Congress

why the Supreme Court would routinely rule in favor of Trump, even in extreme ways

the ultimate selection process of the Democratic candidate for president

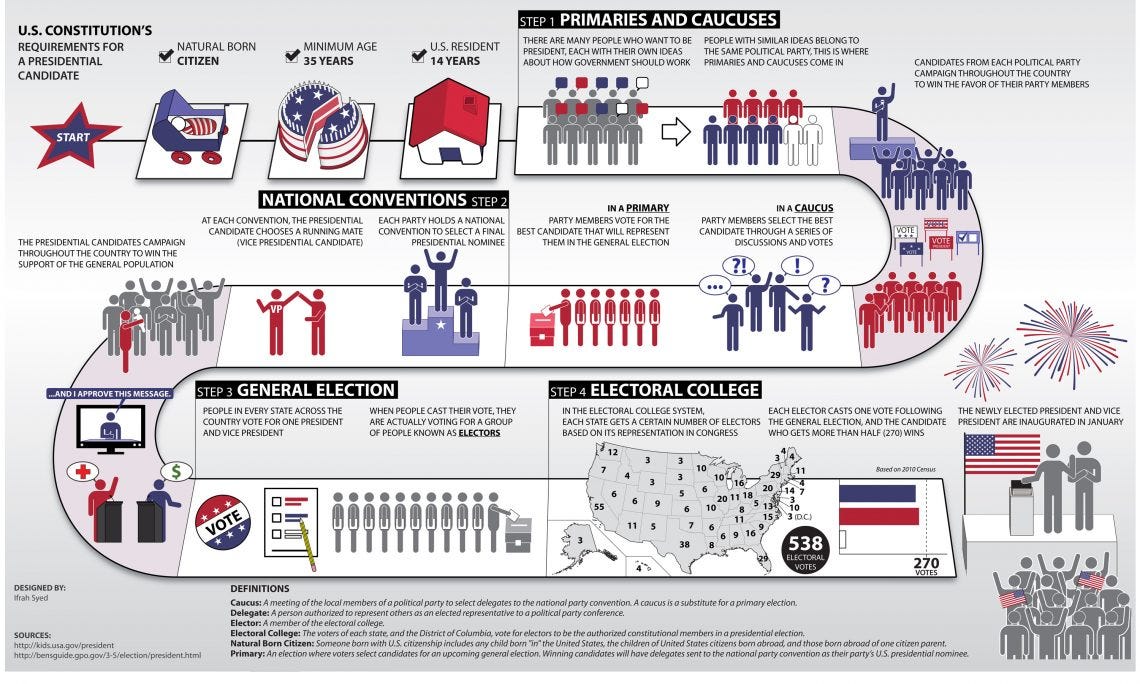

On that last point, for instance, here’s a chart that would have left you radically unprepared:

And I daresay we stand a good chance of seeing this chart challenged yet again should there be a knock-down, drag-out fight over certifying the election results. There’s no Step 5 there for the House deciding to elect someone different than the electoral college votes, and yet …

Thinking about institutions as malleable instantiations of enduring conflicts among groups—capital and labor to begin with, but extending far beyond that—would help resolve these tensions. It would also help think through the way that institutions are chosen and designed. There’s a reason, for instance, that some Democrats were pushing for an open convention to choose a new candidate—and there’s a reason that Biden, the base, and a big chunk of elites chose to go in a different direction. Institutions are chosen because actors have preferences over outcomes, and designing an institution that made the ultimate result an open, contestable choice was a stealth way of objecting to the much more plausible and easily coordinated path by which Harris could move up one rung to the top spot. Those concerns might have revolved around electability, but they could have also well been a way to shove a more right-ward, business-friendly candidate into the presidential spot. (And, for any individual Democratic leader, electability and ideology, to say nothing of race and gender, could easily present themselves as being the same thing.)

Now, the hell of it is that when you start talking about fancy words like “institutions” and “instantiations” and so on, people assume that all this fancy academic jargon is meant to obfuscate—excuse me, “hide”—reality. But it’s not! It’s a way of talking about the reality that lies under what we see. When we talk about the general way that filibusters work (that is, by burning time to force concessions), or when we talk about the general way that agenda control works (that is, by limiting options to produce a preferred outcome), we’re not trying to avoid talking about “real issues” anymore than a plumber uses their tools to avoid talking about a stopped drain. Rather, we are talking about the concepts that explain why it’s hard to pass spending bills through Congress on time, or why members of Congress use Instagram, or why a president might decide not to be a single-minded seeker of re-election.

When you have some comprehension of these abstract rules, thinking about specific circumstances becomes much easier. Why did Joe Biden choose Kamala Harris? He could have endorsed any option (and many were arguing for the convention), but by making this choice he ensure maximum control over the situation, made an ally of his potential successor, and left on terms that kept his reputation more intact. Why is it that members of Congress chose to go public with their views on the presidential ticket—a seemingly settled decision in which they had no (real) official say? It is because their own reputation and power in the Democratic Party hinges on how well the party does—and, in some cases, on speaking on behalf of influential donors and other constituencies, which is a form of representation that may not be polite to mention but is very, very real. (Why, for that matter, did AOC and Bernie choose loyalty as their strategy with respect to Biden? Because it was a defensive play against moderate, centrist factions, and because it was an offensive play designed to get concessions from the embattled Biden camp—all while showing Harris that they were willing to be team players.)

Teaching about politics as abstractions and examples, then, is an honest dodge. It’s a dodge because it minimizes the risk that you’ll have to junk all of your lectures because of a headline in the New York Times. (Although Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine did kill my entire syllabus for Russian Foreign Policy in the spring of 2022. Thanks, Volodya.) It’s an honest dodge because the stuff that amateurs think should be the content of politics courses is best kept to panels and assignments. Teaching the enduring concepts from a broad range of examples is a way of future-proofing a course that might otherwise be based on the narrow range of behavior any “normal” period of politics will provide.

So where does that leave us? Well, in part—it’s genuinely time for some game theory, and a whole bunch of other theory too. Should Republicans consider ditching JD Vance? They should at least have whispered conversations about it—he’s a pick for turnout, not for persuasion. Who should Democrats pick for VP given that Republicans could dump JD? Any elementary game theory course will remind you to take your opponent’s potential reactions into account, not just the move you hope they would make. What looks like the right choice to counter Vance might be ever so slightly suboptimal against a non-Vance candidate—but then again, there’s a pretty good argument to be made that junking Vance would be lunacy for Republicans and, in particular, would make Trump look weak. Hey: game theory can incorporate non-rational motivations!

More generally, students and teachers alike of politics at the intro level should focus a little less on explaining what should be going on according to the playbook and a little more time talking about the fundamentals of politics—an approach more familiar, ironically, to our comparativist colleagues. The institutions are in flux and they’re going to be in flux for a long time.

![Political map of the world, April 1989]. | Library of Congress Political map of the world, April 1989]. | Library of Congress](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!WJtc!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fffb883f5-0853-44ca-bc9b-69ea6e8a059b_1995x1099.jpeg)

So many voices around our university emphasize the teaching of specific skills to make students “career ready” - it’s reassuring to see someone else calling out the value of learning to make sense of what’s happening.

"Thinking about institutions as malleable instantiations of enduring conflicts among groups—capital and labor to begin with, but extending far beyond that—would help resolve these tensions."

I also do wonder if some of the nature of the enduring conflicts have shifted. Biden's relatively low popularity relative to economic fundamentals and actually having delivered on catch up growth for quartiles is contrary to some of my enduring conflict intuitions. And obviously some of this is just competing identities and rural and urban and education differences becoming more salient and all that. But I think some of what leads to my own sense of being unmoored is the global headwinds on social democracy even in those countries that are delivering on the promised agenda. My own intuition is that growing wealth for median laborers dilutes the power of working class identity. That said, those are more vibes than an actual concerted study of the literature on a fairly obvious hypothesis,