States' Wrongs

How moving across state lines teaches you that federalism bites

About Systematic Organization

I’m Paul Musgrave, a political scientist and writer. This is Systematic Organization, my newsletter about politics and the study of politics. The title comes from a line in The Education of Henry Adams:

Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, had always been the systematic organization of hatreds, and Massachusetts politics had been as harsh as the climate. The chief charm of New England was harshness of contrasts and extremes of sensibility—a cold that froze the blood, and a heat that boiled it—so that the pleasure of hating—one's self if no better victim offered—was not its rarest amusement; but the charm was a true and natural child of the soil, not a cultivated weed of the ancients.Everyone agrees that presidential leadership matters.

This week, I moved, and so we’re talking about what makes federalism annoying.

States’ Wrongs

When you start a newsletter, they tell you to keep to a consistent schedule. Since my target is a newsletter delivered to you every Friday, I’m trying to live up to that commitment—even though nothing went according to plan last week.

One thing that did go right was publishing this article about how Trump has weaponized wasting his opponents’ time, which is online now at the Washington Post and will be the lead story for the Outlook section in print on Sunday.

Anyway, we moved. Mostly, it was because of pandemic. We chose our apartment in D.C. to take advantage of urban amenities, not to be a permanent work from home solution. So, like the protagonists of a New York Times trend story, we fled to the suburbs for a three-bedroom unit with twice as much room.

Moving from the District to Virginia while retrieving a storage unit full of belongings in Massachusetts was always going to be a hassle. It turned out to be an adventure, featuring downed power lines, quarantines, and a moving process so awful that the best mover on one leg was the guy who drank Heineken tallboys to hydrate. And, mostly, it reminded me of all the downsides of federalism.

License plates: America’s monuments to federal annoyances (Via Pexabay)

There are a lot of defenses of federalism, like those in Jenna Bednar’s The Robust Federalism, and they mostly amount to elaborate justifications of why dividing power yields efficiencies. Claimed efficiencies come in various flavors: tailoring policies to the preferences of different populations, balancing government against government, allowing for policy experimentation, and so on.

All of those principles are nice to read about, but I’m not interested in high-minded debate at the moment. Mostly, I want to focus on some of the costs federalism imposes on ordinary people in ordinary ways—little frictions that spring from great debates about what sovereignty is and should be. Making the abstract real reminds us that there are tradeoffs beyond those that theorists postulate.

I don’t pretend to provide a balanced assessment of federalism. Obviously, during a time of Trump, the benefits of having state governments that aren’t run by a corrupt president are obvious. (Can you imagine Betsy DeVos as the sole minister of education for the United States? My British readers probably can.) But hey—this isn’t Systematic Assessment of Evidence, it’s Systematic Organization of Hatreds.

If it were a systematic assessment, though, I’d point out two big things. First, the “resistance” justification for federalism is a second-best argument. If government policy should be tailored to the population’s preferences, why doesn’t that argument scale up—why isn’t the population of the nation taken into account as a population whose preferences should be respected? And why use state or provincial boundaries that don’t change with the population as the units by which policy flexibility should be delivered? (It’s truly absurd to suggest that New York City has more in common with Buffalo than Jersey City, but just try rearranging the boundaries of states to reflect this.)

So what are the hassles of federalism? I see three big ones: license plates, taxes, and school curricula.

“License plates” here stand in for a raft of frictional costs of moving. Are you moving across one arbitrary line to another? Congratulations, here’s your taxes. For me, today, that was $200 in fees for new licenses and registrations, coupled with a full morning’s work lost. (And I’m not slamming the DMV here: the VA DMV was very good, the best of the four DMVs I’ve interacted with in the past six years. The worst? Pennsylvania, which has a bizarre non-governmental contract system that I’m sure makes sense to Dwight Schrute and nobody else.) Oh, and would you like to vote? Here’s another form.

I know there’s a lot of arguments about why we can’t have a national license plate or a national driver’s license, or even an ID. But on the other hand: why can’t we? This isn’t really a fundamental issue of state’s rights—just wave the interstate commerce wand and boom, a minor hassle disappears. And we have had to make up all sorts of clunky workarounds to address the problems not having one standard creates, like the fact that Real ID is optional (I had to pay an extra $10 for this because, you know, at some point I’d like to fly ever again).

Taxes are another one. State income taxes are annoying already (but thank you, taxpayers of Massachusetts!), but there’s a special fun that comes with moving at any time other than December 31. Do you enjoy paperwork? Here, enjoy filling out multiple state income tax forms. This is a core function of sovereignty, of course, but the effect is for the state to continually push off the burden of compliance onto ordinary citizens (and big firms), and it’s really damn annoying to have to do everything twice (or, for me once, three times).

Then there’s the school curriculum problem. As with everything, this is a stand-in for a raft of problems involving devolving major aspects of life to state legislatures, which are full of many bright and competent people and also many people who are uh less so. And so we end up with school curricula that reflect the relatively random distribution of preferences and competence that gets to each state’s general assembly, rather than anything that looks at all planned. It’s a great system if what you want is a complete inability for any college professor to assume that any student knows anything in common with any other, to take just one personal downside to it.

This problem takes other forms. Journalists loooove to say that the United States is the only major country that doesn’t offer paid maternity leave—which is true! Kind of. As with all things, this varies state by state (although not that much, with only five states and the District offering paid family leave). It’s both harder for any state to afford this policy on its own—if Minnesota enacts it, watch your firms leave for Wisconsin!—and easier for entrenched interests to defeat it piecemeal than in the national parliament.

Indeed, one reason to dislike federalism that’s a little more balanced is that states are immovable but populations are mobile, making it harder for states to capture the full returns of their investments in things like education. Invest in your state’s universities—and watch some other state gain an educated workforce. One way to end that, of course, would be federally funded education in a much more sensible way than we currently do.

There’s other problems that come with this as well. California can in many ways act as a de facto national standards-setter because its market is so large that its nominally state-level requirements can require manufacturers to adjust to them. (This has been a pillar of U.S. environmental policy.) Texas, notoriously, does the same thing with many school textbooks, which it buys on a centralized level and which most other states don’t.

I wish I could say I was pondering all of this during the move from hell. I thought about it a little bit as we made a daring raid into Massachusetts, currently under strict quarantine, to retrieve our belongings from a storage unit (which we did, in record time, and without talking to anyone besides the U-Haul rental guy and our moving helpers).

But I forgot it on the last part, as I watched our DC to VA movers get aggravated with each other. One thought the other was surly, the other thought the first one was lazy, and as an impartial observer I can say they’re both right. The lazier one worked smarter but also took a lot of breaks—and, sure, it was hot, but like I said, I don’t think that Heineken is an approved way to rehydrate. The surlier one probably lost the argument when he started punching the other one, knocking him to the ground and kicking him repeatedly in the head.

It was all resolved, kind of (and if you’re in the DC area and looking for movers, I uh have some suggestions). Yet it didn’t put me in a frame of mind to be well disposed to all the other hassles of moving.

What I’m Reading

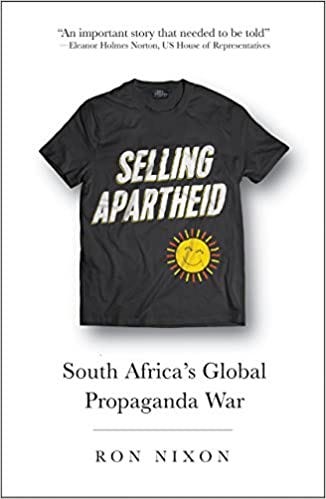

This week, I’m featuring a book about transnational politics.

For a long time, the study of transnational activism was the stuff of leftist and liberal international relations’ scholars dreams. If you were in grad school in the 1990s and 2000s, pretty much everything you read about the subject was a series of feel-good stories in which garment workers in Bangladesh organized to pressure American college students to lobby the U.S. government to improve working standards in Dhaka. Important stuff, but also so tilted to the left that it’s my genuine go-to for an example of how “liberal bias” in the academy can affect studies.

There was, after all, another side to the story: the rise of conservative or right-wing transnational activism. Clifford Bob studied this well in his The Global Right Wing and the Clash of World Politics, which includes studies of how the NRA went global, for instance. To some readers, this will be an even more inspirational story, but I’m sure that for the people celebrating the pressure campaigns I described above it was less heartening reading.

Ron Nixon’s Selling Apartheid picks one thread from this broader tapestry of right-wing transnational organization: the propaganda effort by the Apartheid South African government to influence opinion in the United Kingdom and the United States. Nixon shows how the Apartheid government funneled millions to create front groups, bring opinion leaders and politicians on luxury tours, and otherwise lobby for the government in London, Washington, and beyond.

The detail here is impressive. And if you’re in tune with contemporary politics, you’ll know that these tactics continue to be used—and Nixon will make you skeptical of anyone who begins spouting stuff that’s pro-[insert country name here], especially if they’ve done so after their Instagram shows them in a five-star hotel in that country a few weeks prior.

Nixon might have gone a little deeper in investigating exactly how these funds changed anyone’s mind, or what the value of these representations were, since presumably most of this money flowed to people who were natural allies—but much of the art of political influence lies in generating gentle slopes that tip the balance of decisions invisibly, and the overall scheme of U.S. and U.K. policy toward South Africa’s Apartheid government suggests that these dynamics were in play. For showing how governments can exploit transnational ties and exert influence almost invisibly, Nixon does us a service.