I’m Paul Musgrave, a political scientist and writer. This is Systematic Hatreds, my newsletter about my thoughts regarding politics and the study of politics. The newsletter takes its title from a line in The Education of Henry Adams:

Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, had always been the systematic organization of hatreds.

This week, we’re talking about the politics of the dress.

Role-playing games

Yesterday, former representative Deb Haaland was sworn in as the Secretary of the Interior, one of the country’s most powerful officials. Haaland made news because she is the first Native member of the Cabinet (although not the country’s highest-ranking person of Native ancestry, who remains Vice President Charles Dawes). This has prompted me to offer some reflections on the public roles that Cabinet officials play and how the media understand them.

Interior might be the most underrated Cabinet department, although that’s mostly because its powers are so unevenly distributed in areas and among populations who aren’t in the traditional elites. West of the Mississippi, and especially west of the Rockies, the federal government’s immense landownings make it an imposing and omnipresent reality in a way that Easterners rarely experience. Interior’s remit includes mining and grazing, water and science, and, especially, the federal government’s complex relations with Native and “insular affairs”—the closest thing the U.S. has right now to a Colonial Office. (Awkwardly, in the House, this means that the congressional oversight of "indigenous peoples” falls under…the Natural Resources committee, a position that used to be taken, ahem, more literally.)

Haaland thus occupies the summit of a number of key environmental, economic, and political relationships, including the federal government’s government-to-government relations with hundreds of Native nations and communities. This is the unmarked and underappreciated third kind of sovereignty in the United States, next to federal and state; it’s not often taught in civics or U.S. politics courses, but, indeed, tribal sovereignty is real and it matters for millions of people.

Haaland will be called upon to represent the federal government to American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities and to oversee the government’s Bureau of Indian Affairs (a good pick for, historically, one of the eviler agencies in the federal government) and other agencies. She’ll also, as she did splendidly as a member of Congress, represent Native communities to the federal government and as a high-profile official. This piece in Indian Country Today makes that case well, and Secretary Haaland made clear from the beginning of her term, when she pointedly chose to speak first with Native media (as Indianz.com reported), that she has a sense of how to conduct her office.

I’m a fan of Haaland’s, inasmuch as one can be a fan of a politician, and I think she’ll handle the tough job well—certainly, I hope she will. That includes navigating the complexities of tribal relations with each other and with the federal government; Native interests are not monolithic. Some tribal governments want Haaland to make mining easier, for example, not harder as most Democrats would prefer.

What’s interested me as much as anything is how much coverage of Secretary Haaland’s swearing-in focused on her dress. Literally.

The New York Times led one article on her inauguration with the slightly cringe phrase “Forget pantsuit nation” but mentioned, accurately, that Haaland has long understood sartorial representation:

Wearing traditional dress has become something of a signature for Ms. Haaland during big public moments. In 2016, she wore a classic Pueblo dress and jewelry to the Democratic National Convention; in 2019, when she was sworn in as one of the first Native American members [PM note: this is not even close to accurate; Haaland was one of the first Native women members] of Congress, she did the same, including a red woven belt that was more than a century old. And in January, at President Biden’s inauguration, she also wore a ribbon skirt, one in sunshine yellow, with a burgundy top and boots.

Her outfit when she was sworn in to Congress was similarly striking (even if the high-res public version disappeared with her House Web site) and featured traditional Pueblo clothing (she is a member of the Laguna Pueblo):

Two things interest me here. First, when Rep. Haaland represented her district, she represented her heritage. When Secretary Haaland represents the country, she chose a ribbon skirt from the firm Reecreeations (buy your own!). That seems like a conscious choice about representation in a sense that’s more than personal.

Second, sartorial representation isn’t just limited to folks who aren’t White. You can’t avoid making choices about how you dress; you can only avoid making conscious decisions about them. And recent secretaries of the interior—especially the calamitous Ryan Zinke—have also made pointed statements with their dress.

For instance, here’s Secretary Zinke at the U.S.-Mexico border:

Zinke, a former Montana member of the House, is also choosing to represent his people. His traditional big belt buckle, “cowboy” hat, blue jeans, and incongruous button-down shirt all reflect Western U.S. fashion sensibilities and mark him as a member of the upper middle class and gentry, a group that includes car dealers, general contractors, ranch owners, and local politicians. His use of these sartorial symbols telegraphs whom he represents, and whom he is choosing to ignore (Easterners, liberals, the Establishment, to name a few).

Zinke understood symbolism bluntly. He required his staff to raise a special flag when he was in the Interior headquarters. He rode a horse to work on his first day in the job. And in office he pushed an agenda friendly to mining companies, ranchers, and others who helped install him in office. Later, he was forced to resign for standing out for abuse of powers in the Trump administration.

Reporting and analysis of costume and the roles political actors play shouldn’t be limited to the unusual, like the first Native person to serve as Interior Secretary. We can, and should, mention these sorts of displays all the time.

What I’m Reading

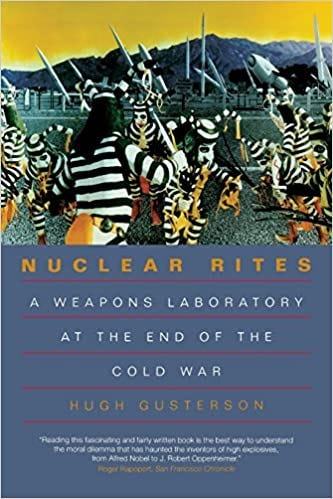

This week, I’ve been reading Hugh Gusterson’s Nuclear Rites: A Weapons Laboratory at the End of the Cold War.

Gusterson investigates the anthropology of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the waning days of Reaganism and the Cold War. He uncovers the status signifiers, practices, and disciplining procedures of weapons scientists and their relationship to the outside world—both the local community and the broader society that funded and feared them. In a twist, he also investigates how anti-nuclear war activists, among them himself, disciplined themselves into a state of terror akin to devout Christians anxiously awaiting the Second Coming. The crux of the book is about struggles over knowledge and ways of knowing, and who is allowed to be an authority, with the LLNL scientists firmly believing that practices like nuclear testing constitute a source of scientific and ritual knowledge while also contesting the ability of non-physicists to discuss nuclear weapons and their advocates fighting them on each step. Well-written if a bit of its time, I found it worth reading.