Peace without victory

Why you should not want the Ukraine crisis to end with a victor or vanquished

I’m Paul Musgrave, a political scientist and writer. This is Systematic Hatreds, my newsletter about my thoughts regarding politics and the study of politics. The newsletter takes its title from a line in The Education of Henry Adams:

Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, had always been the systematic organization of hatreds.

This week, we’re talking about the politics of the Ukraine crisis. This is prepared as part of a talk I’ll give on a panel later today on the Ukraine crisis for the University of Massachusetts Amherst School of Behavioral Studies.

Peace without victory

The most obvious battlefields of the Ukraine conflict is the one of petrol, guns, and death—the clashes in and around the cities of Kyiv, Mariupol, Kharkiv, Odessa, and others. That dimension of this war, the physical and kinetic dimension, is one that has yielded its share of surprises, not least in the determined Ukrainian resistance and the surprisingly poor to date performance of Russia’s military.

Those surprises, in turn, have allowed other theaters of the conflict to come into play. As The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson writes, those other battlefields are the global economic, political, and social ones. Here, Russia has fared even worse, with a stunning array of sanctions and blacklists deployed against it and a remarkable, even genuinely unforeseeable stiffening of Western alliances against Moscow. Had Ukraine collapsed early, or had some Russian missile or Spetzsnaz group eliminated the brave Zelensky, then these operations may have ended very differently, but as of now the solidification of a global anti-Russia bloc has taken root deeply.

Different battlefields operate at different scale. Russia’s subpar military performance will eventually be overcome by brute strength. It is likely that through sheer scale and an increasing political willingness to inflict military and civilian casualties Russia will be able to squeeze even the most valiant Ukrainian resistance. (And we should not assume that we will forever see videos of brave Ukrainians resisting without arms—at some point, rules of engagement will change, curfews will be enforced, and defiance will be brutally suppressed.) In pure military terms, Ukraine is unlikely to win this part of the war.

Yet Russia seems equally unlikely to win the larger war—the global political and economic one. What had been a sea of contending narratives about the Ukraine question in the West has collapsed into one master narrative: an evil, expansionist Putin bent on exterminating democracy itself. (The retroactive reclassification of Ukraine as not just a democracy but a full democracy, even an exemplary one, has been stunning; it should be enough to say that the weak have the right to sovereignty without overly valorizing what was a regime with its own, pronounced weaknesses.) This ideological shift has justified truly remarkable uses of Western economic and disciplinary power, from the freezing of financial assets to an assault on Russia’s ability to be a part of the international community, indeed of any international community.

We should not underestimate Russia’s own weapons in this economic war, including its dominance in energy, resources, and agricultural markets (for those of us who grew up under Soviet times, the notion that Russia is a leading food exporter is a startling but crucially important discovery). It also remains to be seen how many months the West, particularly fickle American public opinion, can actually withstand higher energy prices, not to mention the even higher prices that ending carve-outs for Russian energy would require. The indirect effects (such as the greater likelihood that high gas prices could help deliver one or both houses of Congress to the Republicans, weakening Biden’s hand) should also factor into these calculations.

So the question becomes: where should we go from here?

My answer is that once this immediate moment of crisis has passed—once there is a battlefield pause or some limited gains that allow the Russians the confidence they need to enter into negotiations seriously—serious diplomacy will need to press to create a peace without victory.

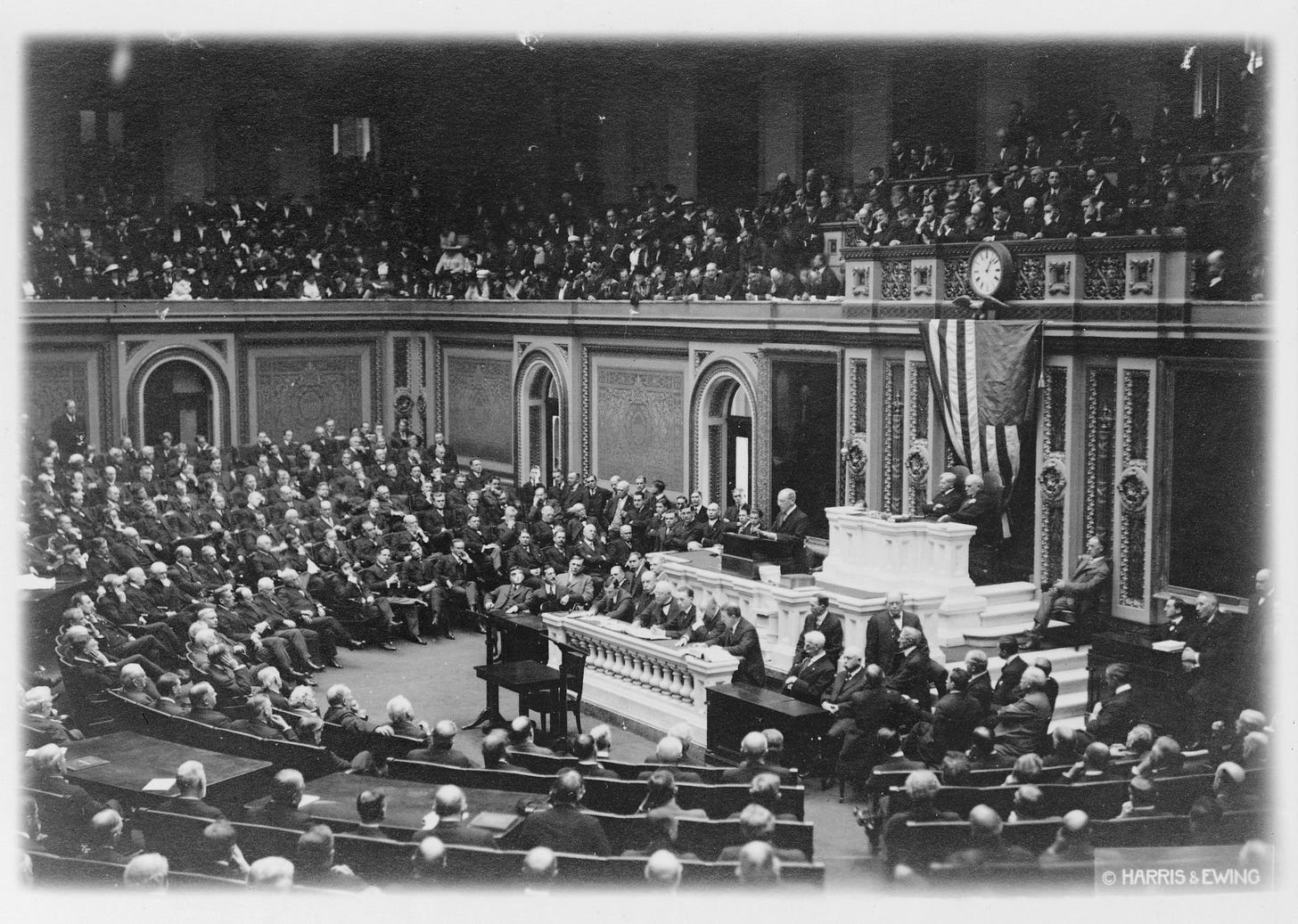

The phrase is Woodrow Wilson’s, and although I am not a fan of Wilson’s I am a supporter of this particular speech. Wilson delivered the address in January 1917, when he had been re-elected but when the United States had not yet entered the Great War. In its pivotal passage, he argued

[The goal] must be a peace without victory. It is not pleasant to say this. I beg that I may be permitted to put my own interpretation upon it and that it may be understood that no other interpretation was in my thought. I am seeking only to face realities and to face them without soft concealments. Victory would mean peace forced upon the loser, a victor's terms imposed upon the vanquished. It would be accepted in humiliation, under duress, at an intolerable sacrifice, and would leave a sting, a resentment, a bitter memory upon which terms of peace would rest, not permanently but only as upon quicksand.

To some, “Wilsonianism” is the very definition of idealism. At times, it is. In other times, as with this passage, it is the soul of realism. Wilson is offering a sacrifice of idealism defined in terms of morality and justice in order to build what another president would later call a lasting structure of peace.

(To be sure, the memories on which Wilson drew to understand the bitterness of the defeated were his own childhood memories of growing up White in a post-Civil War South, an era that he would later deride as a time of carpetbaggers and Northern domination. I certainly do not endorse the roots of this observation. I do, however, believe that Wilson’s diagnosis of the way that a peace—even a morally justified one—that leaves a power embittered and dissatisfied, and willing to renew conflict later, is one that should not be allowed.)

I understand why Wilson would note that “it is not pleasant to say this”. To speak of Ukraine with anything less than a full-hearted expression of solidarity with that nation of victims leaves a taste of ashes in my own mouth. Yet it is also the case that one must think the unthinkable in order to discern ways out of a terrible situation.

This discussion is intimately connected to the current discussion about “off-ramps”, by which people both mean the ways that Putin could exit his current policy of confrontation and the way that the West can someday end its policy of economic coercion against Moscow. At a time when civilians are being targeted and activists passionately call for “no-fly zones”, it is not pleasant to say that we should be thinking about how to bring this conflict to an end. Yet stopping the killings in Ukraine and avoiding a wider conflict are imperative.

This is not to say they are worth any cost. Aggression must be stopped. Conquest must be visibly demonstrated not to pay. Solidarity with the people of Ukraine must be maintained (and planning for the postwar period should include massive relief projects for the immediate and medium-terms needs of Ukraine’s civilian and military infrastructure; at least one country should be built back better). And that means that a firm, unyielding line must be held against Putin’s aggression.

Yet it also means that, as Dan Drezner has written, the goals behind the sanctions must be firmed up. In particular, it means disclaiming regime change in Russia as a goal. Putin has no legitimate security concerns regarding NATO or Ukraine’s alignment; the past few weeks have conclusively settled the argument about who threatens whom.

Yet, legitimate or no, Putin has a clear interest in his regime’s survival. Dictators have no retirement plan. There are likely no inducements, buy-outs, or exiles that Putin would accept in preference to using any tool—any tool—to remaining at the head of the Kremlin or leaving in a body bag. And the turn in recent decades toward pursuing justice even against dictators who leave office voluntarily has made such a bargain harder to strike.

One option seems to be waiting for an internal coup to remove Putin. Yet would that really be preferable? It would only pose in starker terms of crisis—a coup in a nuclear-armed state!—the same question about what terms the sanctions should be ended and bridges be rebuilt between Russia and the rest. Those goals would still have to be clarified, including the fate of officials like Sergey Lavrov, the foreign minister, and Sergey Shoygu, the defense minister. If the real roots of the crisis are a sincere belief in Western threats, it is possible that whatever follows Putin could indeed be a harder-line regime, bent not on peacemaking but more effective warmaking. (I think this is unlikely to be the case; the prime mover of the war seems to be Vladimir Vladimirovich himself. Yet sometimes we have to admit that any regime is hard to parse from the outside, and the war cannot have had a constituency of just one.)

Even if a coup would be welcome, then, it would not be a solution. And so the conversation about what the West’s war aims in this political and economic campaign have to be discussed. The settlement of reparations, a progressive series of confidence-building measures, and a roadmap to the at least limited participation of Russia in international institutions and activities would require years. Yet this, unlike regime change, is a series of options that could be acceptable to Russia—even if it would prove dramatically unpopular (and likely criticized at every turn by a postwar Ukrainian government wreathed in the laurels of at least a moral victory).

A peace without victory would be morally unsatisfying. The rebuilding and reforging of a new Ukraine (and the reinvigoration of the West) would be the more appropriate outlets for that zeal. Yet the cold truth is that, just as it is not in the West’s interest for Russia to triumph in the military battlefield, it is not in the West’s interest for a massive economy, a major nuclear power, and a pivotal defense exporter to remain permanently embittered and hostile to the West. A peace without victory is a peace without humiliatoin.

If nothing else, global problems including climate change will indeed require Russian cooperation (as will more pressing problems like Iran, or to a lesser extent North Korea). The road to such a “reset” is currently jammed with the detritus of Russia’s aggression. Yet that does not change the long-term necessity of rebuilding a relationship with Russia—even if that means a patient application of economic and political containment for months or years. A peace without victory may require a struggle that lasts for some time.

One final point bears noting. Wilson’s idealism led him to try to make collective security the basis for a postwar settlement. A combination of many factors—his arrogance; his illness; his racism; the desire of the West for a punitive settlement; the accident of the Senate’s two-thirds rule; the simple difficulty of avoiding large-scale war—scuttled that idea. In the same way, one easy (if wrong) “lesson” of Ukraine’s victimization is that countries should not give up their nuclear weapons, and that ultimately only force guarantees security. This could spark a new round of proliferation.

Yet the alternative would be to seize on the moment as a means of reinvigorating efforts to stop the spread of nuclear weapons. The nuclear sword of Damocles Moscow has invoked should remind us that the prospect of nuclear annihilation is ultimately a threat to us all. Given the stakes, a renewed effort to push against such prospects would seem to be worth the candle. It is surely no more idealistic than the idea that deterrence will forever prevail over accident and temper.