Partial-Equilibrium Trump Fallacies

Sensible moderation isn't the right way to understand policy responses now

“Well, everyone knows Custer died at Little Big Horn. What my book presupposes is … maybe he didn’t?” — Eli Cash, The Royal Tenenbaums

One of the many disadvantages of intelligence is that it can perversely make it hard to see what’s in front of your face. Intelligence, after all, reduces the cognitive burden of rationalizations, and rationalizations feel like analysis, and function in many similar fashions in many instances. That, at least, is my generous explanation for why so many people are falling into the trap of taking each Trump administration policy in isolation and then trying to see how they can strike a compromise with it.

I call this “partial-equilibrium Trump analysis”, because it assumes that there is a reasonable Trump that makes policy in isolation on each issue. Because policy is made in isolation on each issue, there’s no need to consider whether actions the administration is taking in other domains could inform assessments of this policy. Because Trump is presumed to be reasonable—I’m not saying this; I’m describing the assumptions necessary to make this verkakte perspective work—then any deficiencies in the policy can be treated as if they resulted from insufficient information or analysis. Under those circumstances, it follows that it would be productive to inform the White House of consequences of their actions or to suggest ways to reduce the harms that such policies would impose.

Sometimes, these partial-equilibrium Trump fallacies (PETFs) manifest as social-media comments by those sympathetic to Trump gently suggesting ways to make cost-cutting less dire. Sometimes, it animates op-eds in influential newspapers suggesting ways to fulfill the reasonable, centrist goals that surely we all share, like reducing administrative bloat. And sometimes it appears to animate how captains of industry conduct their assessments of whether to support Trump as “good for business”.

Always, or to a first approximation always, this is a mistake. I can’t believe that, nine years into Trump as the defining political actor of our time, people are still saying, in essence, “Everyone knows Trump is a stubborn, vain, and untrustworthy political actor. What my analysis presupposes is … what if he wasn’t?” And yet! There are still people—some with good degrees and high salaries supposedly deserved for the sagacity of their analyses—who are committing partial-equilibrium Trump fallacies every day on matters directly affecting them!

It’s tempting to dismiss these folks as silly or worse. But I think we need to take PETF seriously. It’s the moderate/sensible-centrist version of Trump Derangement Syndrome, and it’s far more pernicious because its symptoms are adaptive in helping people fit in with a lot of white-collar and sensible folks whose reactions to Trump, say, threatening to impose tariffs on Canada is to say “oh, he’d never do that, the consequences would be too dire.” PETF exploits the individual and social bias toward assuming that extreme predictions must be the result of unfair analyses, and folks committing PETF thus can be rewarded for putting forward sensibly moderate compromise proposals.

One reason I suspect PETF is so attractive is that it fits neatly into the “bargaining” phase of grieving, and I do think that grief is the appropriate way to describe the reaction to the loss of power that an entire class is feeling. (Mostly, too, that’s justifiable, because this loss of power will cause unimaginable human harm.) When you look at how the anti-Trump coalition has responded to this second setback, it’s clear that some are choosing anger and others are mired in depression; denial is present as well but it looks more like withdrawal than an insistence that, say, Kamala is really the president.

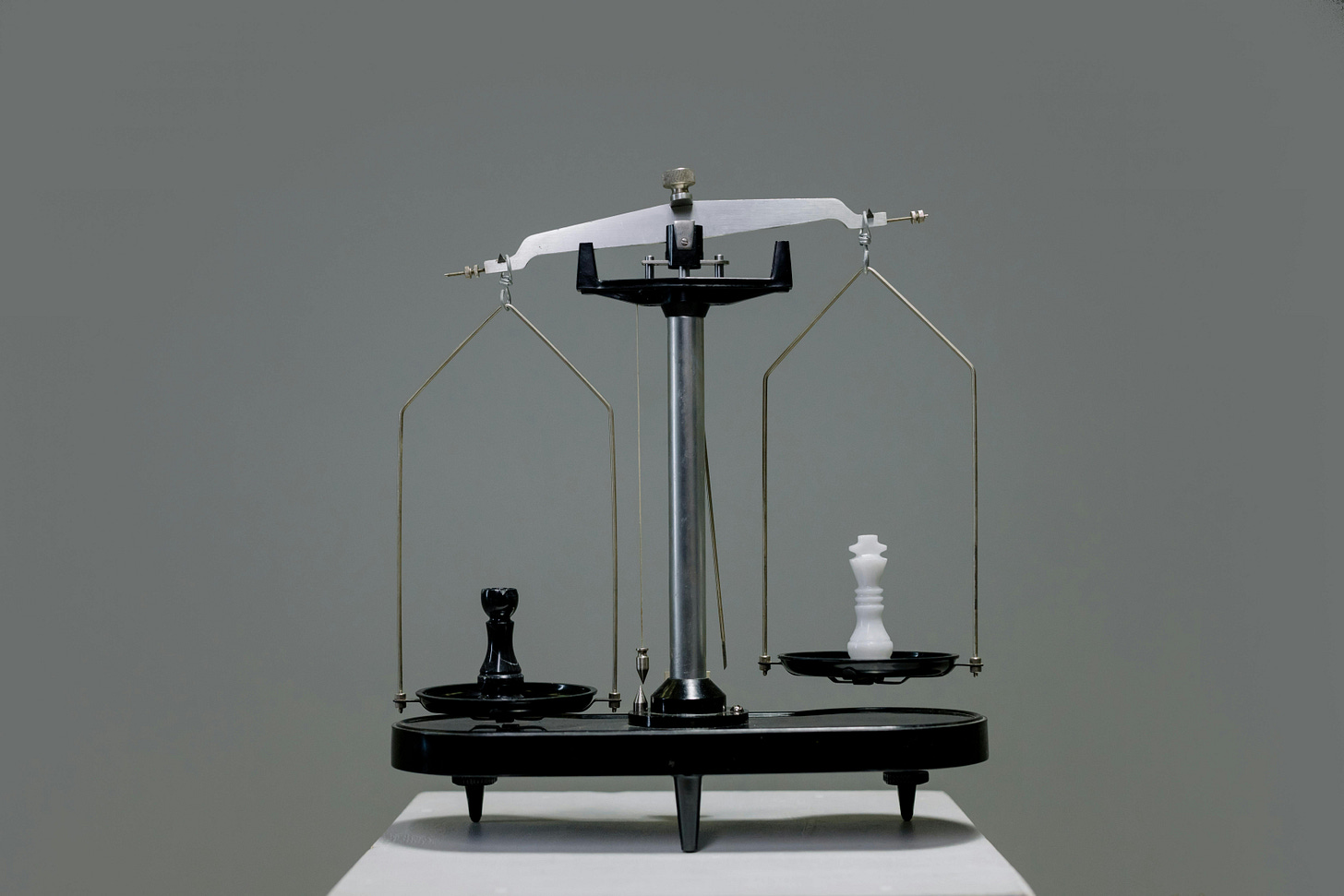

Yet PETF is pernicious because it turns out to serve as an effective wedge against the formation of any sort of broad anti-Trump movement. If your first instinct when confronted with a Trump proposal is to find common ground and affirm some part of it—the universities are too bloated, Ukraine has many domestic political problems, Greenland has a lot of minerals, whatever—then this will feel like sensible analysis free from bias. And there will often be a germ of truth in a Trump proposal. But seeking to engage with those proposals as if they come from a George H.W. Bush is a mug’s game, because any agreement will be taken as a concession.

This does, to be clear, present very bad risks for analysis. It’s bad to deny things that are true! So, no, don’t deny that some things are bad—but don’t make those admissions central to your analysis, and don’t deny the equally true fact that Trump proposals must be analyzed in context and on the basis of what we know about Trump.

The trick to sound presentations of analyses of Trumpian risks is twofold. First, lead with the concrete harms and disadvantages of a given proposal and show that the policy would fail to address its target (it probably will) or that it would meet that target only at unacceptable costs. Second, point out that this isn’t a policy proposed in a vacuum, and that we can point to other actions to show that the administration isn’t serious about its goals. (Reducing waste, fraud, and abuse? That’s rich coming from the guy who fired all the inspectors general and installed a loyalist kook as FBI director.)

The habits and manners of professional workers are ill-adapted to a hostile environment. They can be functional and even desirable in many situations! But we shouldn’t expect that habituated responses will be appropriate, and a little bit of metacognition will go a long way in properly calibrating responses—and expectations. Reflexive impulses to compromise will only make things worse.

This polling from yesterday...

The Australia Institute surveyed a nationally representative sample of 2,009 Australians about President Donald Trump, security and the US–Australian alliance.

The results show that:

• Three in 10 Australians (31%) think Donald Trump is the greatest threat to world peace, more than chose Vladimir Putin (27%) or Xi Jinping (27%).

• Most women (56%) feel less secure in Australia since the election of Donald Trump; only 13% of women feel more secure.

• More Australians prefer a more independent foreign policy than prefer a closer alliance with the United States (44% v 35%).

• Half of Australians (48%) are not at all confident that Donald Trump would defend Australia’s interests if Australia were threatened, compared to only 16% who are very confident that he would do so.

• Half of Australians (51%) think Donald Trump’s election is a bad thing for the world, twice as many as think it is a good thing (25%).

https://australiainstitute.org.au/report/polling-president-trump-security-and-the-us-australian-alliance/

As I get older, I have noticed more and more how we humans are eager to make peace with the present and the status quo--even if we opposed it before it became so. I am sure there are myriad reasons for this, but psychologically I think we just don't like the stress of constantly admitting that the world is a hostile and dangerous place. It's much easier to assume and trust that those in charge must be, basically, responsible and ethical, even when the contradicting evidence is right there.