Merry Tiebout Sorting!

A Hallmark movie about HOAs and lessons from social science

Homeowners associations (HOAs) are ubiquitous in the U.S. housing market, with more than a quarter of Americans living under one and as many as two-thirds of new construction falling under one.

They are also widely hated. On any Internet forum—let’s say “Reddit” for shorthand—you will soon encounter stories about zealous HOAs making other residents’ lives miserable. HOAs, it turns out, enforce a lot of rules—search for “common HOA restrictions” and one of the first results will specify fifty such rules you should expect, including

restrictions on swearing

limits on alcohol use

bans or limits on renting and Airbnb sharing

noise

party attendance limits

home occupancy limits

limits on the number and size of pets

requirements for storage and appearance

and basically just a whole bunch of rules that an unpleasant or litigious neighbor could enforce.

It’s a small wonder, then, that many folks who live in HOA communities hate them. But as a social scientist my natural question is: if they’re so hated, why are they so plentiful?

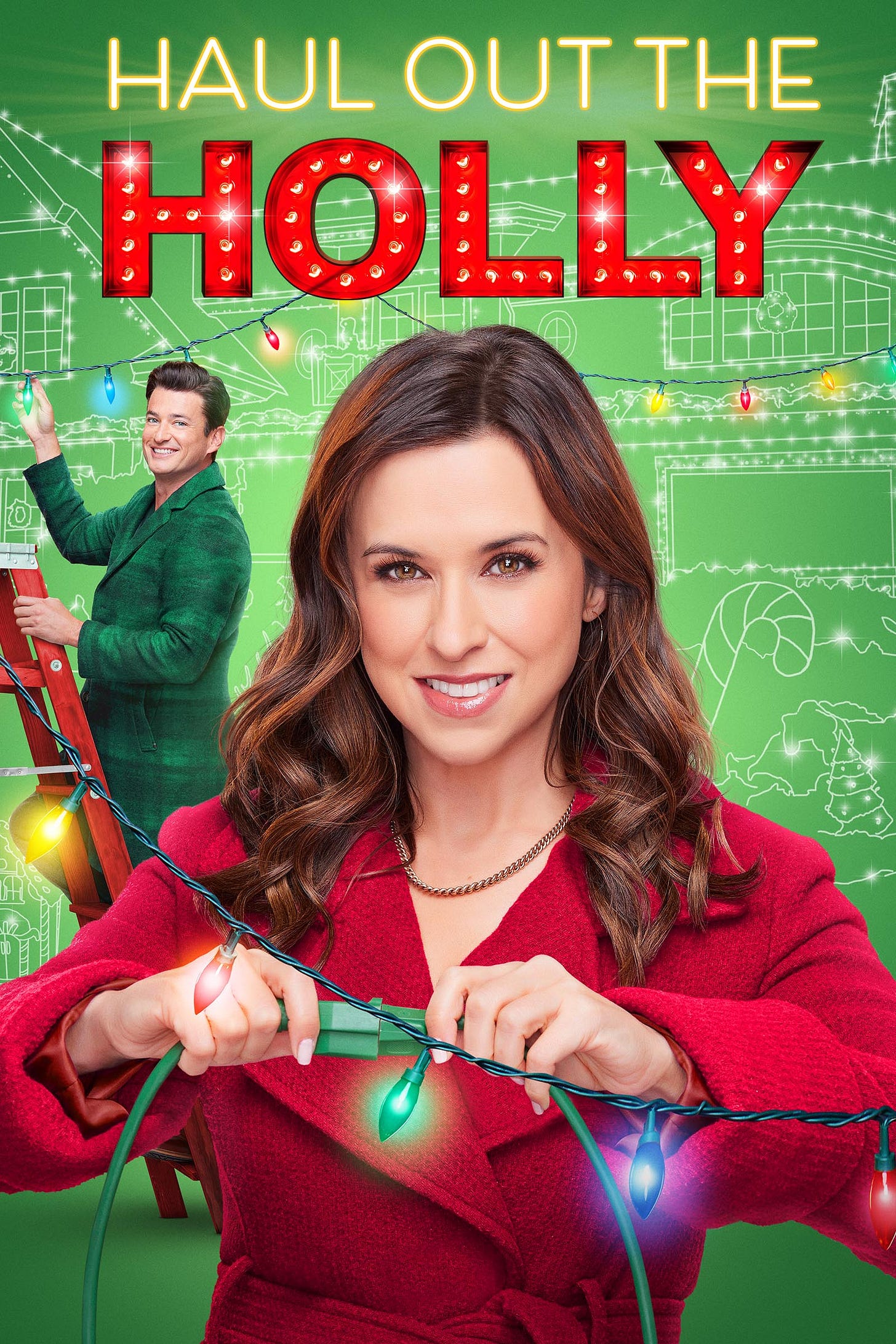

But as someone who has no intention (or, in this interest-rate environment, capacity) to buy a house, either under freedom or HOA rules, why was I thinking about this in the first place? It has to do with Haul Out the Holly, a 2022 Lacey Chabert vehicle for the Hallmark Channel. Yes, HOAs are part of cable Christmas movies—and, in this case, they are the crux of the matter.

The whole plot revolves around HOA requirements, as the (still younger-)middle-aged daughter of Boomers (Chabert) takes over her parents’ house for a Christmas getaway—and has to decorate their house to comply with HOA rules. Yes, really: “When Emily unexpectedly spends the holidays alone at her parents' house, their HOA insists that she participate in its many Christmas festivities.” Yes, someone measures the size of the outdoor nutcrackers.

I’m not a law-talking-guy, so I don’t know if an HOA could enforce requirements to have Christmas decorations, but given that at least one HOA has allegedly enforced a dress code for garage sales (and another association requires tenants to be hip artists), it’s not too far out there. And at the very least the premise seemed plausible enough to get not just a first film but a sequel greenlit (Haul Out the Holly 2: Lit Up). Granted, this is a genre that routinely goes to the well of “heir of European micro-principality entranced by twenty-something American career woman”, but we should assume that the older, homeowning, female audience of the Hallmark Channel has at least encountered HOA requirements in a way they haven’t encountered princes.

The movie is charming and perfect to have on as something that nobody is watching. (I’ll let you know about the sequel.) As I mentioned, though, it spurred me to think more about HOAs and governance, not least because, as scholars like Jill Tao and Barbara C. McCabe have pointed out, HOAs are essentially private governments. They are in theory less powerful but in reality more binding for many behaviors than traditional, public governments.

And although many complain about HOAs, their ubiquity and growing presences suggests that being subject to a neighborhood-level regime with the sort of moral governance codes I more often associate with theocratic or autocratic regimes (or colonial Massachusetts, but I repeat myself) is attractive for many. That HOAs also “tax” their members to provide heightened services—trash, security, garbage removal, commons, etc—also raises at least the possibility that existing U.S. government arrangements are failing to provide collective goods that people want. But under what conditions are these goods provided—just for people like us or (more optimistically) just when governance is easy to monitor?

Political science has much to say about homeowners (they vote, a lot, and institutions are responsive to them) but not about HOAs per se. And so I turned to other social sciences to learn more about all of this.

Tao and McCabe describe the origins of HOAs in response to the problem of how to provide legally mandated common areas and infrastructure in the 1960s and 1970s. HOAs legally exist as a master deed restriction set up in advance of development (and so you can’t opt out), and are governed by a board elected by HOA members (that is, property owners—a notable but not wholly uncommon deviation from “one man one vote” to “one property, one vote”, although notably this gives second-home owners and non-citizens the right to vote).

HOAs can self-manage their services or contract with vendors to provide management. This is, as Nelson describes, a major change from traditional arrangements in which property owners owned homes and collective goods were provided by local (township, city, county) governments, with little intermediate (neighborhood-level) coordination. Further, the development of HOAs meant that “many fine details of neighborhood land use—house color, placement of trees and shrubbery, minor building alterations, parking rules, and so on—came under the direct collective control of neighborhood residents.” (I wonder whether this revolution in property ownership and governance, even moral regulation, flew under the scholarly radar screen more because it happened in the suburbs, which academics hate, or in the rich neighborhoods, which academics can’t afford.)

One might imagine, as Tao and McCabe describe, that HOAs would be attractive to people who are interested in paying more for services than the median resident of an urban jurisdiction. This is related to the proposition known as Tiebout sorting: that people who can will move to communities where their preferences for taxes and spending are accommodated.

It’s a neat neoliberal solution to how to get people to provide common goods: you literally vote with your feet until you create communities where everyone is willing to either pay no tax and get no services or pay high tax and get plentiful services. (Like many neoliberal propositions, it’s silent on what happens to people who can’t afford to vote in this manner.)

HOAs are one possible manifestation of Tiebout governance. Further, not only does it promote matching among preferences, but HOAs should provide an incentive-compatible way to provide services: since every homeowner directly benefits from efficient management (in terms of lower fees and higher property value appreciation), the rewards to free-riding in “public” deliberation should be lower and the quality of government should be higher than in more diverse and democratic governments. And, indeed, a survey of community managers by Tao and McCabe finds that HOAs provide more and deeper services than the local government minimum. At the same time, their results suggest that HOAs foster relatively little distance from local governments—instead of being enclaves unconcerned with the community around them, even gated communities appear to be engaged, a trend that appears to accelerate as communities become more developed.

It is true, however, that such communities are not chosen at random. Clarke and Freedman find that HOA residents are “more affluent and racially segregated” than residents of nearby neighborhoods. On the other hand, using Zillow data, they find that HOA prices are higher than similar houses outside HOAs by about four percent on average. They further estimate that $1 in HOA dues produces $1.19 in returns. The laundry list of HOA restrictions appear to be prized by at least a large number of consumers. (One wonders whether the Christmas decoration HOA requirement would have a premium, because it would attract like-minded residents, or a discount, because it would turn off many would-be buyers.)

A good deal of this surplus in Clarke and Freedman’s study appears to derive from weak local governance, particularly in the South—weak local governments may have produced HOA desirability (optimistic) or rich white families may have seceded from their municipalities (pessimistic). Indeed, one advantage for HOA members is that HOAs can undertake projects that strained local governments simply can’t—but it’s also possible that municipal governments can’t undertake such projects because HOAs provide them for voters who would otherwise need to demand them from local governments. Research by Cheng and Guo in Florida, with a high density of HOAs and laws requiring disclosure of relevant data, suggest that higher HOA prevalence does lead to downward pressure on taxes.

In that case, as Cheung et al note, “there may be welfare losses incurred by individuals who do not belong to an HOA and now enjoy lower quality services”—that is, HOAs could be good for members but bad for others. Such problems could be taken to the limit, as in parts of Atlanta and Los Angeles, if HOAs or confederations of HOAs seek to secede from their parent cities altogether.

The “racial overtones” (as I’m sure New York Times headlines would put it) of such secessionist movements are obvious. Moreover, if you think about these developments from a sociological or historical lens rather than an economist-pilled Tiebout lens, the purposes to which people will put voluntary segregation and extreme regulation are obvious in a society as colored by race as the United States.

Nelson notes that “as legally private entities, the new neighborhood governments could discriminate in some areas forbidden to public governments”—and although what he means are the development of age-restricted communities (a very legal and very uncool means of discrimination!) when one reads the list of restrictions one also thinks of, well, what Jim Crow would have written if he were trying to comply with federal housing legislation: “the manner of dress, the playing of music, and other forms of individual behavior that public governments are more reluctant to regulate.” And while, as a middle-aged person myself, I very much understand the desire to regulate some of these behaviors, one also can’t help but notice that there’s no HOAs where people have to dress like Snoop Dogg or drive low-riders. Instead, the ideal HOA citizen just about everywhere is an extra on The Truman Show, except somehow whiter. (The Truman Show was filmed in Seaside, Florida, which was privately developed and is apparently managed by … an HOA.)

Yet the story could be still more complicated. If wealthy homeowners don’t like a city or feel like their taxes are too high for services provided, they can always leave—a possibility that American suburbanites are familiar with. In that case, HOAs could serve to entice wealthy families to remain in the city, to at least some benefit for all. Optimistically, in a series of experiments, Cheung et al find that offering wealthy citizens of cities an HOA-like option makes it likelier that they will choose to stay within city limits even at high tax rates. On the other hand, Cheung and Meltzer also find that HOAs in Florida are formed more quickly in non-Black and non-immigrant tracts—which may suggest that although their effects on causing residential segregation is limited they also hardly help to accelerate integration.

Social science is hard, and coming to an understanding of what is happening is hard enough without then going through the moral calculus of whether it is morally desirable or not. But it does seem like the HOA revolution marks an important shift in U.S. self-government, and particularly in how the middle and upper-middle classes govern each other. It also appears likely that this means that associational life will have a racial and ethnic tinge, as opportunities for participation in this form will be marked by the ability to purchase a house.

The larger implication of these findings seems to be that there is something holding back local governments from being higher-tax, higher-service jurisdictions. Crucially, it’s not cost. I think that it’s likelier to be something more political—either wealthy residents’ uncertainty that other voters’ preferences (and particularly preferences for redistribution) could be tempered by exit options, or a belief, or gut feeling, that those people won’t spend their money as well as others.

These are big questions. One small point, for me at least, is that it’s telling that HOAs aren’t particularly weird. Why aren’t there more Haul Out the Holly -style HOAs? Where’s my chess neighborhood? Where’s Mos Eisley, the HOA for people who want to live in a sanitized hub of scum and villainy? Why can’t I live in a neighborhood that looks like the Warner backlot—or a fake Left Bank? Is it really the case that HOAs’ powers will only ever be used to regulate neutral colors and shrubbery to cover up air conditioning and never to require people to greet each other in Irish? In other words, are we all fated to live in a society that’s increasingly just going to be as surprising and individual as a midseason episode of Fixer Upper?

Bibliography

Cheng, Shaoming, and Hai Guo. "The interplay between private and public governments: the relationship between homeowner associations and municipal finance." Local Government Studies 47, no. 5 (2021): 759-783.

Cheung, Ron, Timothy C. Salmon, and Kuangli Xie. "Homeowner associations and city cohesion." Regional Science and Urban Economics 93 (2022): 103760.

Cheung, Ron, and Rachel Meltzer. "Why and where do homeowners associations form?." Cityscape 16, no. 3 (2014): 69-92.

Clarke, Wyatt, and Matthew Freedman. "The rise and effects of homeowners associations." Journal of Urban Economics 112 (2019): 1-15.

Nelson, Robert H. “Homeowners Associations in Historical Perspective.” Public Administration Review 71, no. 4 (2011): 546–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23017462.

Tao, Jill L., and Barbara C. McCabe. "Where a hollow state casts no shadow: Homeowner associations in local governments." The American Review of Public Administration 42, no. 6 (2012): 678-694.

I’ve lived under an HOA regime but once, and will not do so again. When I bought that house I didn’t really know how these things work; now I do. What struck me most at the time - this is in Gwinnett County, Georgia - was the dearth of ordinary public goods outside of the HOAs: public pools, parks, sidewalks and paths, etc. Our neighbourhood rules were not awfully onerous - nothing that would rise to the level of Hallmark drama - but the poverty of local public goods (our little city of Bloomington offers much more, and very much more per capita) was not right.

I kept my stay short

When my wife and I went looking for our retirement home in 2019 we had a list of things we wanted, but the top item on the list as non-negotiable was NO HOA. We're pretty quiet people, and take good care of our property, but there's no way in hell we're letting the most anal-retentive person in the neighborhood tell us what to plant in our garden or tell us exactly where we have to store our trash cans.