Making Arguments

The craft of intellectual work

What do professors do?

Everyone’s entitled to a midlife crisis, but some professions seem to never escape the collective existential versions. Intellectuals convert emotions into abstractions; rather than confronting the source of frustrations or disappointments, it’s calming to regard them as though they’re at a distance and amenable to cool analytic solutions. As a profession full of the middle-aged constantly confronted by the refreshments and invincible ignorance of youth, academia is no exception.

Everyone is also entitled to a grievance against the misunderstandings the generalized public holds regarding their profession. Lawyers can groan at lawyer jokes, and politicians can protest that they’re public servants rather than swindlers; I assume even pharmaceutical salespeople can offer some defense of their existence. For me, perhaps idiosyncratically, I bridle at the label teacher. I teach, and it’s an important function of my work, but that’s not the defining characteristic of what I do, nor is it (literally) what I’m trained for. If anything, I regard teachers with a little bit of awe: you do this for how many hours a day?

So what is it to profess? You might think that it’s about expertise—about knowing things—but I’m dubious. We are not, actually, assessed on what we know about the world. Spending time back in the real world convinced me that a lot of us—certainly me—overestimate our knowledge about the world. The arrogance of the booksmart is offputting to the people at the coalface. More precisely, often what we know is of interest only to others in our intellectual communities. Does anyone outside my intellectual circle care a whit about the debates regarding the ontology of Kenneth Waltz’s theory of international politics?

Indeed, not a little part of academic life consists of making bold declarations about what forms of knowledge are irrelevant. John Mearsheimer, for instance, has recently made a heel turn, and a presumably profitable one, of decrying the importance of knowing anything about the specifics of international relations. He’s only the most prominent example of this pathology; any academic who has tried to practice on occasion what one has learned knows that moving from the classroom to the conference room involves a massive effort in turning general theories into applied working knowledge, a form of translation every bit as intensive as turning Mayan glyphs into French poetry.

So what is it that we do? We make arguments.

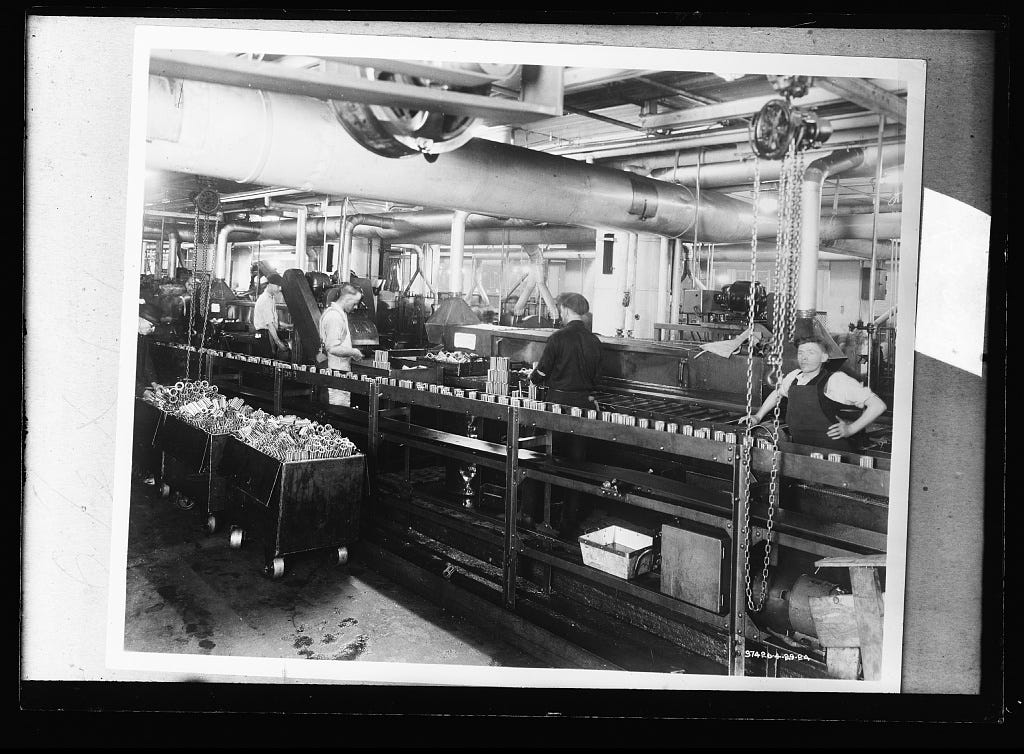

I mean “making arguments” in the same sense that sculptors make statues or factory workers cars. Arguments require structure, evidence, logic, and rhetoric. They need to be cast to fit the requirements of a particular form: blog post, Substack entry, journal article, course lecture, or monograph. Like a product, they must be marketed—that is, literally brought to market—and advertised to potential customers. (Indeed, “marketing” and “publication” share more than a little conceptual overlap.) And like a product, arguments must involve product differentiation (originality) and some form of appeal.

It takes work to make anything. Thinking about arguments as products clarifies that our job is not to think big thoughts or ponder imponderables; no, buddy, you’re hear to turn out arguments. It also lets us think about quality and niche: are we making an exquisite argument to be judged by discerning audiences, or are we making a good-enough subsidiary argument that will bear the load that a larger edifice requires? It also lets us think about why plagiarism is bad—it’s theft. It also distinguishes what’s distinct about professoring from other educational jobs, and why professoring often shares a long, open border with industry (in my world, think tanks; in STEM worlds, industrial research labs).

It also lets us clarify what’s distinctive about academia Lots of professions make arguments, as Dan Drezner points out in The Ideas Industry. Where academia differs is that our remuneration is more loosely tied to the kinds of arguments we make, as well as the liberty we have to choose the arguments that we’ll ship. (More loosely, but not unbound.) And it distinguishes between academia and science. Michael Stevens makes plain in The Knowledge Machine that science rests on the judgment of arguments by participation in a rhetorical game in which evidence is the arbiter of fit—not normative values or aesthetics, still less popularity. Not all arguments are science.

Finally, viewing argument-making as a craft clarifies the different steps on the ideas assembly line that each of us participates in (or the ideas atelier in which we toil, should we not be part of a research lab). Data wrangling, analysis, text drafting, presenting—all of these are functions in the general process of making an argument and preparing it for publication.

This may not be the Ivory Tower. It’s more of a knowledge cottage industry. Yet knowing what we do can help address some of that dread and reconcile expectations with reality. It also shows what we have to offer students and the public: reliably built arguments and mentorship in how to craft the same.

Endnotes

The traditional Chinese calendar contains 24 solar terms—mini-seasons that mark subtle shifts in the course of the year, such as the Awakening of Insects, Minor Heat, White Dew, and Frost Descent. It may be time to replace these with an updated version for China’s COVID-19 calendar, which would include Summer Hope, Provincial Lockdown, and Winter Surge, to name a few. They are certainly becoming wearily familiar.

This week saw Fresh Tightening, a predictable follow-on from False Loosening, which began earlier this month. After the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party last month, some observers hoped Beijing would adjust its zero-COVID policy, and announcements of a dynamic strategy in November bolstered markets, seeming to herald a new beginning. But new outbreaks have quickly dashed hopes of real change anytime soon.

James Palmer, in China Brief by Foreign Policy

We should not be using it as the primary means for measuring learning other than writing itself. Or we should be deciding how to teach content where distinctive expressive writing about that content is simultaneously desirable, possible and rewarded. To me, that at least means much less writing, with much more effort and attention put into the writing that we actually do. It probably also means figuring out how to prompt expressive writing better than most of us do in our classrooms. I suspect for many faculty, asking for maximally expressive and individualized writing is done by assigning open-ended exercises with few rules or boundaries. Instead, we might be asking students to read on one hand the dullest and most conventional kind of “review essay” that clutters the back end of many scholarly journals and on the other hand to read something like a review essay by Patricia Lockwood and ask them which one they’d rather be credited with writing—and which one they’re confident an AI couldn’t have written. Those are very constrained exercises, in their way, but what makes Lockwood expressive and the average journal review essay dull is not just the quality or invention of the prose but the difference between having something to say and having nothing to say.

So the skill we need to re-invest in is simply (not so simply) this: having something to say. Which I think is precisely what writing in college succeeds in absolutely murdering in most students.

Timothy Burke, in Eight by Seven

Great post. Your point about how arguments can be presented in different forms gets to what I see as a real challenge with young academics who have been taught to see their task (and they have often been told this by people who should know better) as to "write articles" rather than to make arguments that can be then be presented, among other ways, as journal articles. There are fields where arguments are disappearing, in a sea of AI-like presentations of regressions, and I don't mean just STEM.

Very interesting!