One of my goals for this newsletter is to add new perspectives to English-language discourses. To that end, from now on, I’ll be collecting my notes on events here in the Arabian Gulf under a new sub-newsletter: Gulf Living. (This won’t change how you receive the emails, but it will help you distinguish the content as you receive it.)

When I was growing up, a big selling point for Wal-Mart was its emphasis on selling products Made in America (even if the “America” in which at least some of those products were made was in the far Pacific, not the rust-belt factories in the iconography of the ad campaigns). Infamously, you basically can’t buy anything good that’s really made in America (states + DC) anymore—just look at the Made in America store, which can help you dress like someone who has strong opinions about different Flying J locations:

The rules for “Made in America” are really strict—all or virtually all of the product must be assembled in the United States. As a result, there is a lot of American manufacturing barred by the label’s rules (Boeings don’t qualify, for one!). That sort of crude protectionist imagery was out of fashion in the academic circuits I traveled. Nevertheless, I find it hard to dismiss the emotional appeal.

In my present circumstances, I buy a lot less Made in America than I used to, because even fewer qualifying goods are shipped to Qatar. What I buy instead are goods that are Saudi Made.

Made in Saudi is a program commissioned by Mohammed bin Salman, now Crown Prince of the Kingdom, as part of the Vision 2030 project to diversify the Kingdom’s economy. You might have heard of one really valuable thing Made in Saudi—hydrocarbons—but this project aims to promote other goods. Tellingly, the emblem centers the palm tree, which is the official symbol of the Kingdom.

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 is probably best known for its megaprojects—the new city NEOM (with a cost in the trillions), an offshore rig-themed amusement park, a Red Sea resort city, and a residential development overlooking the Sacred Mosque in Mecca (I get ads for this one on LinkedIn. A lot). But the quieter iconography of Made in Saudi may not make headlines while still mattering a great deal to what it tells us about identity-making.

As with all marketing, there’s a lot of fluff around the Made in Saudi logo: “Like a star, the palm leaves represent hope and prosperity”; “The trunk, like an arrow, points forward, capturing a country in motion, driven forward by its proud and motivated citizens and residents.” (A deconstruction of the Nevertheless, there is something about a defiantly forward-looking logo for a country that, fifteen or twenty years ago, was routinely described as “medieval”. (There’s a lot of stereotype-busting in the Kingdom’s public identity these days.)

This might be branding or propaganda or whatever you care to call it, but it does mean something about how the government wants others to see the Kingdom—and it also fits, anecdotally, with a genuinely upbeat mood that I see in the Saudis that I encounter (although bear in mind that that’s a select group).

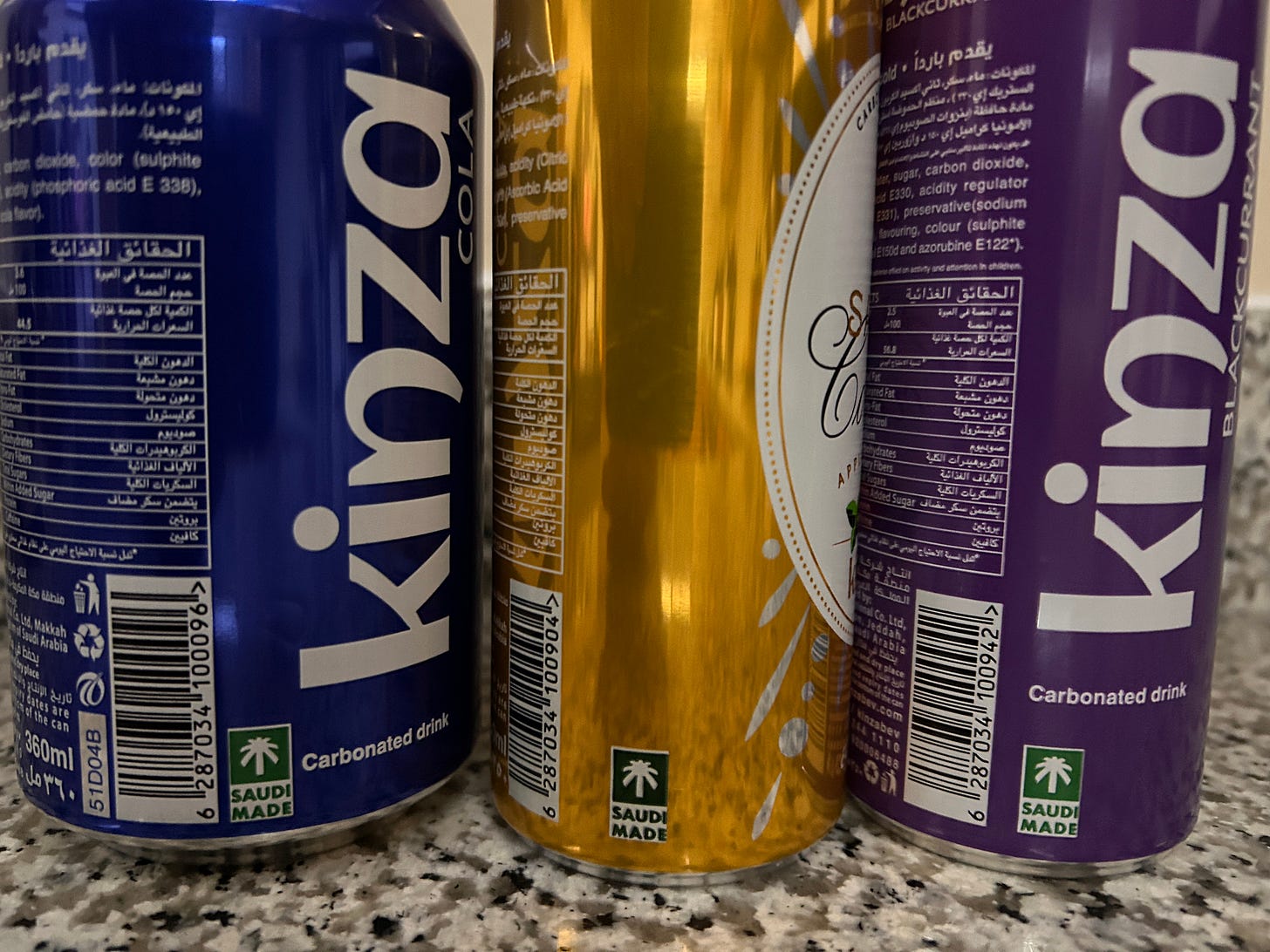

The logo gets affixed to a lot of products—do you need geosynthetic clay liner? Allegedly, there will also be an electric-vehicle marque, Ceer (although I couldn’t find any pictures of any actual vehicles on its Web site). I see it most often, however, on Kinza:

Kinza is a Saudi soft drink company which is so new that it doesn’t have a Wikipedia page yet—which is really bizarre to me because it’s just the soda I drink now. (There’s no bigger meaning behind that choice; it just happens to be particularly good. Not the diet version, which is terrible.)

There’s a lot behind why Kinza is available here. First, I suspect a lot has to do with the informal but very real boycott of Israel-affiliated brands (and an “affiliation” can be at times very tenuous—see this Reddit thread), especially since the beginning of Israel’s operations in Gaza. Second, remember that this is a Saudi soft drink being sold in a country that Saudi Arabia blockaded not ten years ago (it’s Qatar’s only neighbor, thanks in part to KSA’s actions in the early 1990s, which involved deadly armed clashes).

And yet there’s bit walls of Kinza all over the place in grocery stores here. Forget the “cola wars”—it’s the cola peace.

It’s not just soda—Saudi Made juice, too:

There’s also bleach:

And my Tide detergent bears the Saudi quality mark:

This is just not the sort of ordinary stuff that English-language audiences associate with Saudi Arabia—in general, I find that perceptions of the Kingdom are pretty well out of date, reflecting assessments that might have been grossly correct in the Nineties but are no longer. (On my only trip to Riyadh, I was almost run over by a black Toyota Land Cruiser—but when I saw that the driver was a woman, my mood shifted from annoyance to solidarity.)

I don’t have a PR contract with the Kingdom and I don’t work pro bono, but I will simply note that Saudi is changing a lot and fast and in ways that suggest a very different trajectory for its future. More to the point, it’s a big country with a GDP per capita in the same league as Taiwan and South Korea, and the government is trying to show that it has a value proposition for its subjects in a way that is … pretty ordinary. Partly, marks like the Saudi quality label are just a way consumer protection; partly, it’s trying to gin up a market for home-grown brands and products as part of a McKinseyfied import-substitution policy.

There is also something deeper going on, of course. These represent a secular and highly nationalistic branding for a country that traditionally relied on religious legitimation and is named not for a people but for a family. It thus matters that the palm tree is a symbol of national identity, and it’s one that is showing up in unexpectedly fashionable places, like the shelves of a Doha coffee shop-cum-sportswear store:

(Dare I say that the cap is … good? If it doesn’t come through in the photo, it was extremely well-made. And, yes, lids are having a moment in Arabia.)

All of this reflects a pretty intentional project of nation-branding, the kind that reflects a steady, bit-by-bit establishment of a new national identity. If it doesn’t change minds in Europe or America, that may be because people there are not the audience. Not everything gets done for the Western gaze.