Note for subscribers: this newsletter may become an EVEN HIGHER frequency publication for the next few weeks. There’s so much happening and some of them are on my beat. Enjoy the fruits of my hypergraphia stress release mechanism. Also, not to be too YouTube-y, but if you press the heart button at the bottom of these newsletters, it does matter.

The past few weeks of Trump II: Electric Boogaloo have reminded Canadians that being neighbors to the hegemon is nice except when it’s awful. As Prime Minister Trudeau (père) once said, “Living next to the United States is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast, if I can call it that, one is affected by every twitch and grunt.”

My Canadian friends and acquaintances are enraged by Donald Trump’s flippant assertions that Canada should be abolished and in the interim it should be taxed—or, you know, maybe not, just kidding! It’s the 51st state, haha but no really.

The immensity of the Canadian response is big enough to show up in statistics.

There’s been a very Canadian-esque tone to the whole rediscovery of national pride; Canadians have rediscovered a beer commercial (for Molson’s, natch) boasting about being Canadian—but the star is worried about the downsides of patriotism.

And, inevitably, at least one of my Canadian correspondents has apologized for the forthcoming unilateral turn in Ottawa’s policy. You know: Sorry!

All of this got me thinking: if I were in charge of Canada’s grand strategy, what exactly would I be trying to do? That is, what are the options for a post-U.S. Canadian grand strategy?

Phil Lagassé has already written about this, and so have others, but I wanted to work through this myself.

My assumption is that Canada would prefer to remain independent and that this would be a reasonably unified objective (no secessionism, Alberta!). How best could this goal be pursued?

The first question is: can Canada be defended conventionally? That is, can Canada hope to hold out against potential U.S. military coercion? Not, to be clear, because I think that the United States is likely to invade, but because the principal goal of a state that feels threatened should be to guarantee its physical security. Even if victory is not an option (and let’s be frank, we can take that off the table), we can ask whether Canada could inflict sufficient costs to deter U.S. adventurism in the first phases.

I knew going in this would be difficult. Canada has a number of disadvantages in terms of defensibility. Its population centers are near the United States, meaning it has little strategic depth; the United States has the advantage of interior lines, so Canada cannot easily shift forces from one theater to another; it has few major ports, making it easy to blockade.

But I did not know how difficult this would be for Canada. Its military is underfunded and badly structured to deal with a American invasion.

Let’s start with military personnel. It would be unfair to say Canada has none. Relative to the United States, however it has … almost none. Specifically, on the order of 72,000 (plus, Wikipedia tells me, some reserves—but that’s far from enough to change the story here).

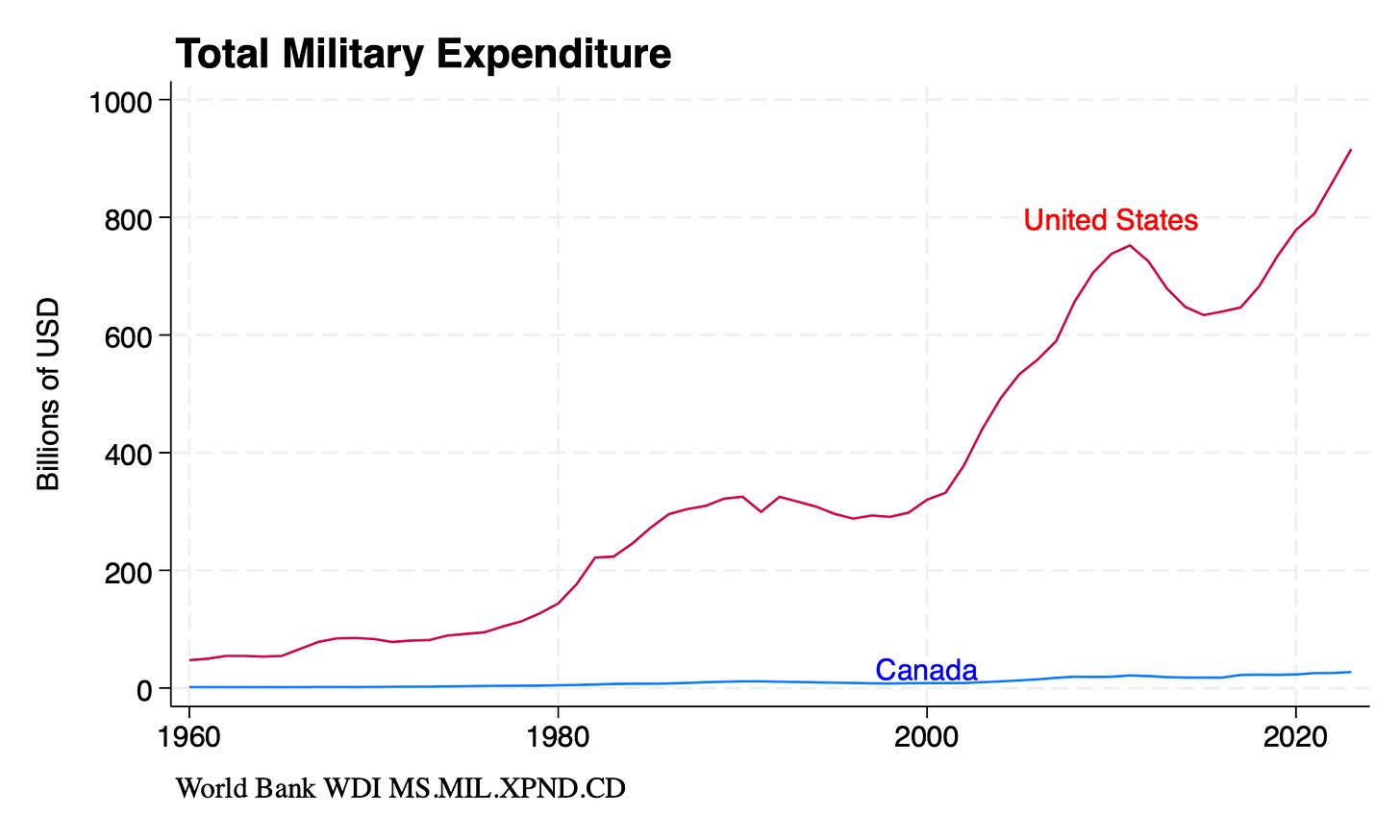

Ah, but what about military expenditure? If you look at Canada’s military expenditure as a share of GDP, it’s not terribly impressive—well under the 2 percent per annum goal of NATO—but it’s far from impossible to imagine that a defense could be mounted with this ratio. Except…

Except that Canada’s GDP is a lot smaller than that of the United States, so the real gap is huge:

“Money isn’t everything,” I can hear you mumble. Of course it isn’t. You also have to take into account qualitative factors, such as Canada having a total of 156 fighter/attack aircraft (they’re F/A-18 Hornets, if you care) which is, by the sheerest coincidence, almost exactly as many F/A-18 Hornets as the US Marine Corps operates. (Yes, the Navy’s army has an air force.) Or there’s the fact that Canada operates 74 tanks; the U.S. Army has (including units in storage, to be fair!) 5,500 M1 Abrams tanks.

Or there’s the fact that Canada does not have—as far as I can verify—any air-defense systems. They apparently just … got rid of them in 2011. (They’ve contracted for some MANPADS and counter-drone systems, but there’s not much that could take down, say, an F-35.)

I’ll be honest: this is is worse than I thought. It’s a far worse correlation of forces than for Ukraine and Russia (for instance). Canada does not appear to possess the mix of asymmetric forces it would need to make a U.S. invasion particularly costly. Nor does it have strike capabilities that would allow it to hold the U.S. homeland at risk. Bluntly, Canada does not appear to have a military so much as it has a light peacekeeping force with some auxiliary forces for the benefit of U.S.-led operations.

The tenor of much Canadian commentary I’ve seen on social media is that these problems can be overcome with gumption and resolve. I’m not that optimistic (and, no, I’m not an op to sew doubts among the Canadian Anglophone public). It’s just infeasible to imagine this degree of military unpreparedness reversing in the course of even a generation unless Canada were to begin plowing massive amounts—on the order of 10 percent of GDP—into its military for a sustained period. As Lagassé also wrote (in much different circumstances), even getting to two percent of GDP was going to be a genuine difficulty. And that’s before we talk about how this would have to be accomplished in an atmosphere of economic decoupling from the U.S.A., which would entail costs of its own, or how that degree of budget increases would require stiff cuts elsewhere.

Conventional deterrence of an invading force by either denial or punishment is off the table.

What about finding partners and allies? The traditional route for a country threatened by a more powerful neighbor is to appeal to that neighbor’s rivals. In this case, that would be Russia and China. Allying with either would pose a major challenge for Canada; even a quasi-authoritarian United States will have more cultural similarities and affinities than Beijing or, certainly, Moscow.

There is, however, another option: Europe. Europe has many elements of a great power’s reach: a respectable arms industry, military training facilities, and experience running larger military organizations than Canada does. If we were to include, say, Japan and (especially) South Korea in the mix, that would also include large shipbuilding and major tank-producing countries (my semi-uninformed assessment is that Germany is more of a boutique producer of MBTs now and that South Korea has more scale to offer). Further, these all offer the sorts of defensive asymmetrical weapons that Canada might want to engage with. As a means of diversifying from a largely U.S.-derived weapons mix, there’s a lot to like here.

However, it’s also hard to imagine security guarantees from Europe being worth all that much. Europe doesn’t maintain large-scale expeditionary forces (at this scale and at this distance, who does) and would not be able to carry out a resupply of Canada in case of serious difficulties (think supply planes and ships having to force their way in). Europe does, however, have 1.5 nuclear powers (counting the UK as one-half because its nuclear deterrent is not independent), which raises another question I somewhat seriously considered:

Should Canada go nuclear?

If you think about this like an international relations realist, the answer is: sure, why not? Nuclear weapons allow smaller powers to threaten to inflict unacceptable damage at low marginal cost—one ICBM with a nuclear warhead is a lot less expensive than a tank division, and Canada doesn’t even need long-range missiles. Classic statements by influential realist thinkers blithely assume that more nukes = more peace. And Canada has sizable uranium reserves and a lot of scientists!

There’s just one problem: this absolutely won’t work.

The most dangerous time for an aspiring nuclear country is between deciding to make a nuclear weapon and possessing it. In that period, rivals know that the country is anticipating becoming more powerful in the future but the country has no power to inflict costs. Its type is revealed but it lacks the means to back that up. Discovery, which is likely, would risk pre-emption (or sanctions, quarantine, etc), which could lead to serious costs of their own. And then we are back in the conventional deterrence world—and Canada has many fewer advantages here than does, say, Iran.

Furthermore, nuclear arsenals are like pharmaceuticals. The marginal cost of producing the second weapon is a lot less than the cost of producing the first one. You don’t just have to produce the uranium or get the bomb designs; you also have to come up with delivery systems, warning systems, command-and-control systems, and a host of other systems that Canada doesn’t have. (Well, I guess you could repurpose the Diefenbunker.) Canada doesn’t have cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, hypersonic missiles, or even nuclear-capable aircraft. I suppose that you could always put a bomb on the back of a Ryder truck and send it across the border, but that has less of a deterrent punch.

I don’t want to exaggerate the costs—North Korea developed an arsenal in a cost-effective manner—but they also shouldn’t be understated, particularly given that the circumstances under which Ottawa would carry out this policy would be much less propitious than those in which Pyongyang has done so. Furthermore, I don’t think that Canadians are particularly eager to play a game of nuclear deterrence—or risk pre-emption.

So what should Canada do?

My best recommendation would be to carry out a program of de-risking and political defensive warfare.

De-risking would include a gradual build-up of Canadian military capabilities, starting with pursuing some modest air-defense and long-range strike capabilities, including surface-to-surface missiles and anti-ship missiles. The good news is that this is probably the right mix to pursue anyway against Russian threats in Europe and the Arctic. Better to develop some capabilities now than try to have to do a crash program later. And if it helps get to 2% faster, so be it.

Political defensive warfare would involve sustained and intensive outreach to European and U.S. audiences. Canada should position itself as a North Atlantic and really Western European country, a natural part of a security community marked by shared values and history. (King Charles could host a summit.) European powers should see their own interests involved in Canada, and Canadian public diplomacy and other operations should aim at that. Demonstrating a willingness to participate in European collective self-defense (that 2% again!) would probably help. The aim of all of this would be to try to raise the chances that, should something bad take place, the United States would feel consequences from a range of other countries and partners.

For U.S. audiences, Canada should undertake aggressive measures to cultivate ties with power structures. They’re not going to like hearing this, but that probably doesn’t mean only engaging with sympathetic groups (academic exchange programs, sponsoring appearances by Ryan Reynolds and Avril Lavigne, etc); it’s going to mean making clear to U.S. power centers, whoever is in charge, the exact benefits, both national and personal, to them of maintaining an independent Canada. (They should also make clear the costs in the long-term of an occupation; the economic math for Canada as a 51st state just doesn’t work, as I wrote earlier, and that was assuming a voluntary union.) Simultaneously, Canada should try to recruit and encourage pro-Canadian elements in the regime.

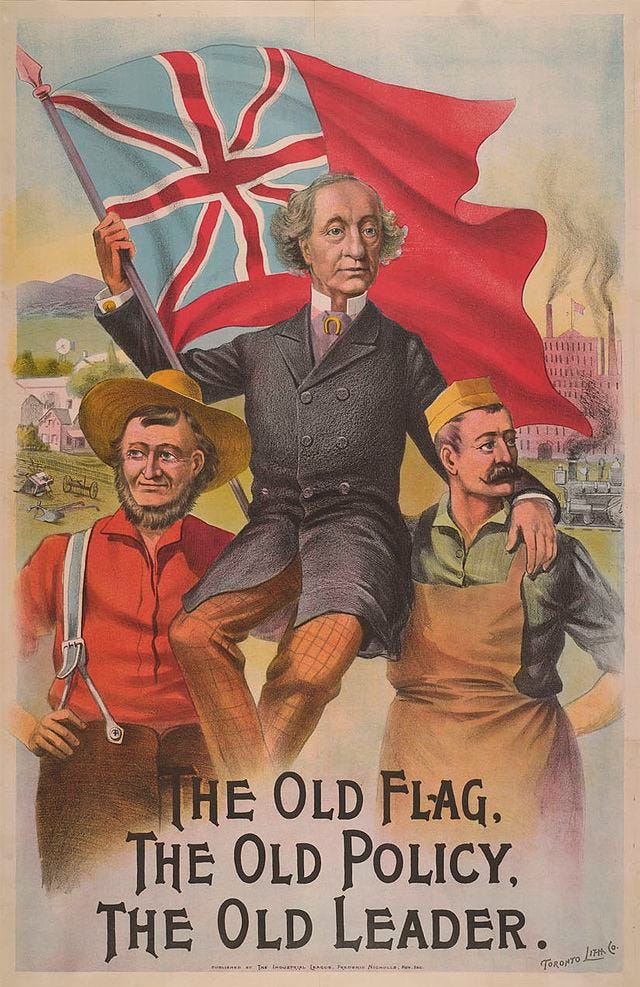

The dire truth is that international trade links are mostly determined by economic size and distance, and that means that Canada’s economy (except its currency!) will be linked to the United States—it’s simply not possible to decouple too much given the size of the U.S. economy and the nearness of Canada’s economic centers. There’s a reason why the long arc of Canadian history moved from London to Washington:

Update: I’ve just realized that this is utterly impenetrable to anyone unfamiliar with Canadian tariff history, and for those few readers unfamiliar with the policy views of John MacDonald, here’s a reference to the 1891 election, a description of imperial preference and Canadian protectionism, and for good measure a description of the Canadian Red Ensign.

(Speaking of London: ask the Brits what it’s like to try to develop deeper trading ties with distant friends when you leave your common market.) Unless Ottawa is eager to pursue a sort of Maple Juche, it’s going to have to work to influence and guard against the United States rather than splashily defying it.

But here’s the good news, such as there can be a silver lining in this mushroom cloud: smaller powers can and do hold their own with greater powers. A smaller country dealing with a larger one focuses its attention on one issue—a larger country is always trying to balance many competing demands and opportunities. (I wrote about the dynamics of asymmetric international relations earlier.)

This is a great piece, and a sobering one. I’m painting with a broad brush, but over the past decades the complacency in Canadian politics, the notion that things will somehow just work out, has been starting to have its effects, in domestic as well as foreign policy (I imagine similar could be said about the UK), an unwillingness to deal forthrightly with major policy challenges (compare to the Mulroney government, for example). And now that a crisis really has hit, with the re-election of an aggressive Trump? I worry.

I wonder if France would lend some nuclear equipment to Quebec, France just need to be sure Quebec wouldn’t use it against Canada