Do you remember WandaVision? The first few episodes were great, as fine television as we deserve from the culturally hegemonic Marvel universe. If you remember (and spoilers ahead for a four-year-old show), they involved Wanda Maximoff, the witchy Eastern European character played by Elizabeth Olson, grieving the death of her android boyfriend (it’s comics) by taking over a town and forcing its inhabitants to take part in sitcom scenarios—the boss comes to dinner, the housewife chaperones the kids—as a coping mechanism.

(You may think this is far fetched, but one Eastern European social scientist of my acquaintance—an extremely distinguished scholar—told me that seeing Wanda’s flashbacks of a family bonding over bootleg DVDs of American TV shows was the most he’d ever felt represented in U.S. media.)

I mention this because the current U.S.-based discourse seems like nothing so much as an reboot of Trump, the reality TV show that is actually reality. Everyone’s trapped on set and we’re all waiting to hear what the next twist will be—a parasocial relationship that also happens to be the driving force of the world’s politics.

Obviously, this is all important, and the fact that serious people are spending their time writing about how they would lead an anti-American cell in the frozen north of Canada suggests that we’re in perilous times. Nevertheless, I would like to take a pause from this and talk about something else: namely, how everyone’s brain, including my own, appears to be broken.

I think about this a lot, like I imagine most of my readers do, because I’m always online and I’m always aware that being online is a terrible thing for me, and probably for society too. Over the past twenty years or so, the adult world that I was brought up to expect—a world featuring travel agents, newspapers, and the nightly news—has been more or less deposed, replaced by a creeping goo of permanent adolescence in which everything is social media.

The change has been fast enough that it’s left architectural remnants. In my university’s student areas, we have large cabinets designed to hold newspapers for students to take and browse—except there are no paper newspapers to fill them. (They’re being used to host brochures instead.) I do not know anymore who the anchors for the nightly news in America are—a shocking turnaround from the circumstances that prevailed when I was a literal toddler and still knew who Peter Jennings was. (Jennings, Rather, Brokaw—the trinity of news authority during my formative years.)

I’m not alone (and not just because these days I live far from the United States). The state of traditional media in the U.S. is beyond dire; the serious, adult, foundational media of my youth is more or less in hospice.

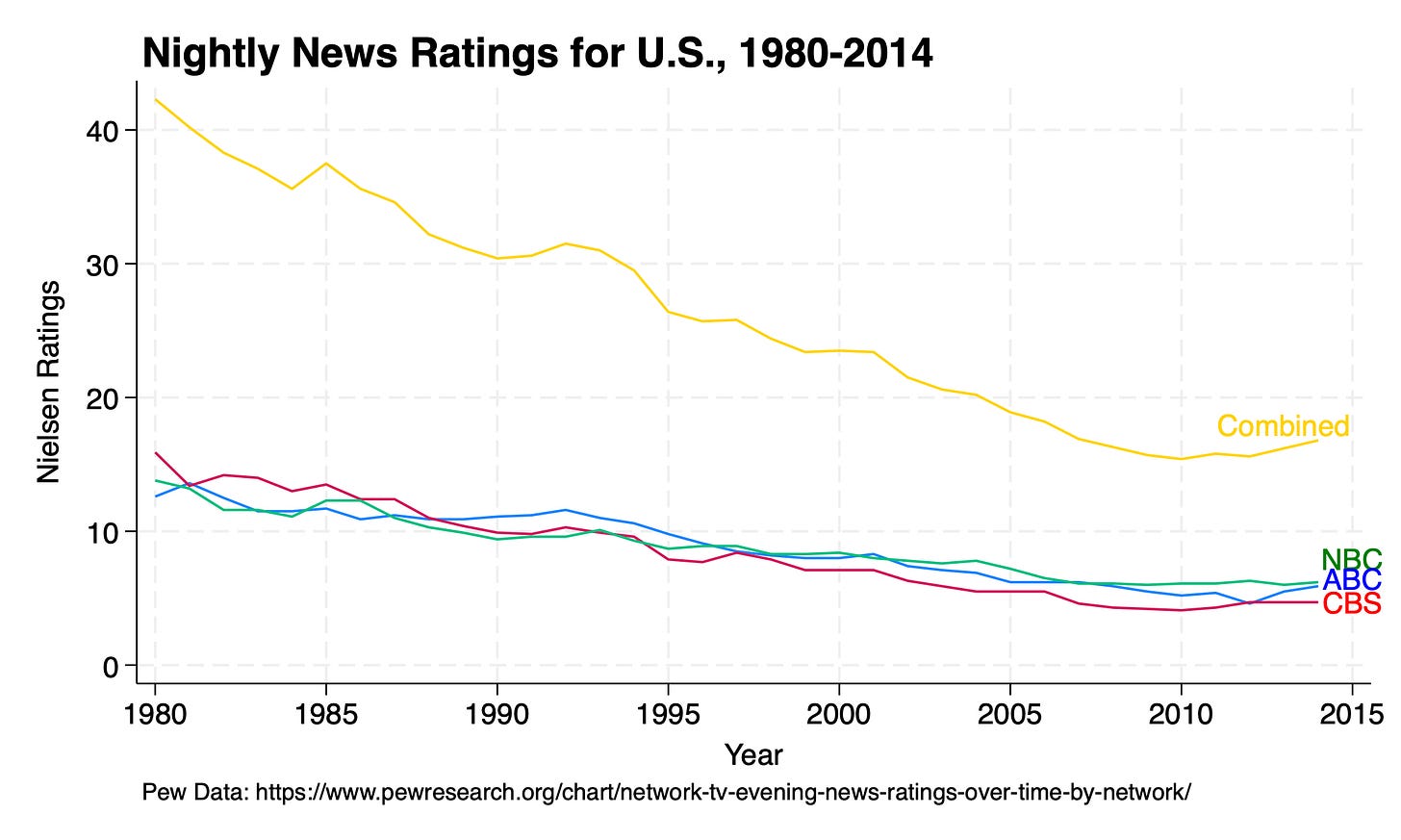

It’s hard to find data past 2014 but the available data suggests that the numbers haven’t improved. Only about 2.5 million people aged 25-54 watched an episode of the nightly news in 2023-2024, which isn’t nothing but is a pretty far cry from what it had been.

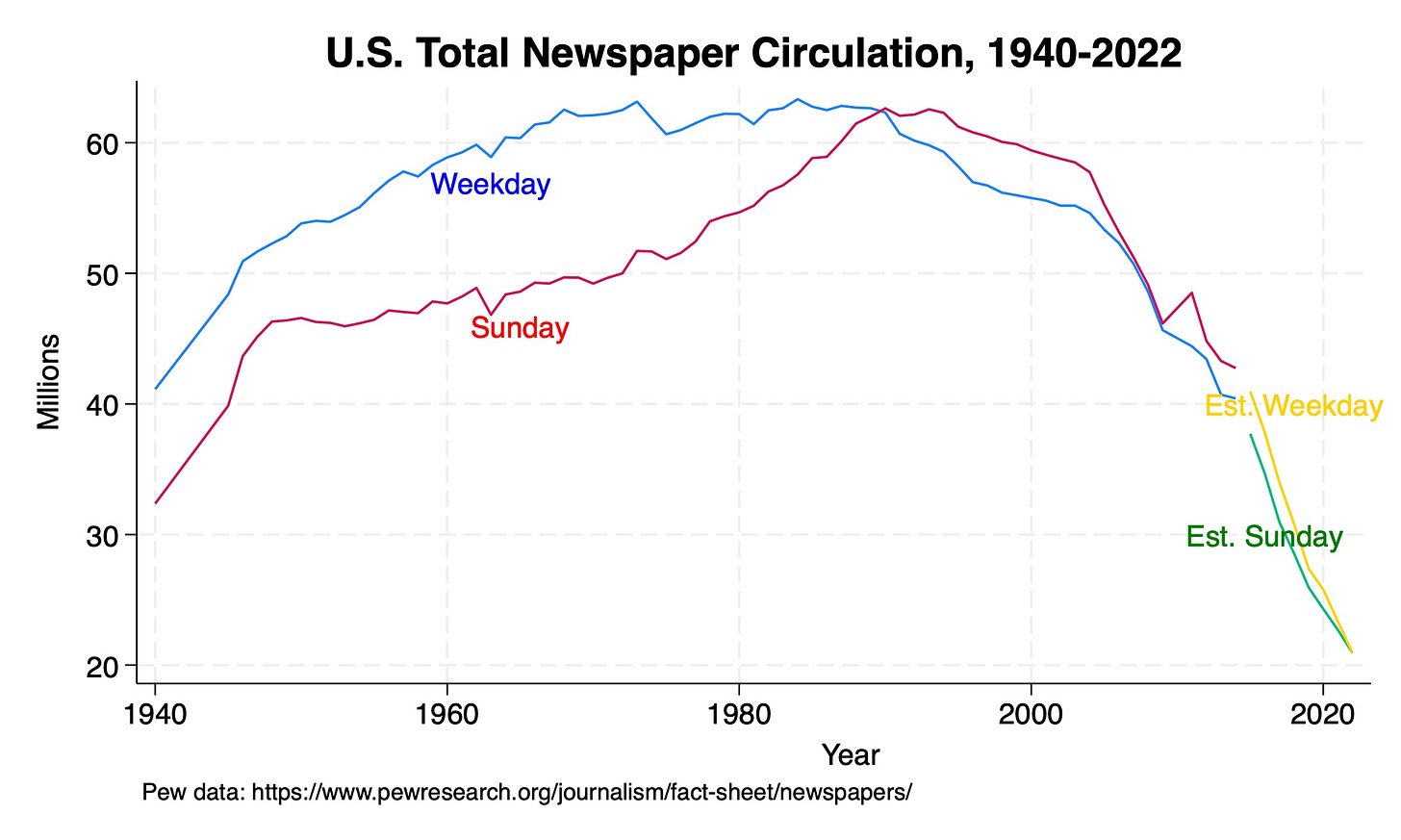

The state of newspaper circulation is even more parlous. Circulation has cratered:

(And, no, digital subscriptions are not enough to reverse this, even if they do show some publications, basically the Times and the Wall Street Journal, doing all right.)

And employment is not far behind (these trends have not gotten better since 2016).

In sum, the “traditional news media” is not long for this world. In its place? Joe Rogan. Steve Bannon. You get the idea.

I’ve been thinking about this ever since Charlie Stevenson, a former professor of mine and the author of a Substack you should all subscribe to, mused back in December—you may remember: the Before Times—about how disconnected he felt from most Americans’ news habits:

But now I’m dismayed to learn that most Americans get their news from sources I never see. A Pew survey last September reported that 37% of Americans “never” get their news from print media and 57% “often” get it on digital platforms, including 25% who “often” rely on social media like Facebook [33%] and Instagram [20%] and TikTok [19%]. I seldom rely on digital sources myself. I don’t even listen to many podcasts. My wife hears them while in the kitchen or the garden, but I find them too long and too linear.

I fully agree with this, especially about podcasts—I’ve used them from time to time but I’m not currently in a podcast phase. Who are these people and where are they getting their news?

But I’m also part of the problem.

I do subscribe to a lot of high-quality news publications (the Journal, the Financial Times even though I can never get their damn app to work, the Washington Post, Slate, Apple News+, Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, and through my employer the New York Times). And yet … what’s my first stop for news? These days, probably Substack. In video form, to the extent I get any news like that at all, it’s … YouTube. (Yeah, I’m addicted to those channels that use satellite photos to count up T-72s in storage in Russian tank farms.)

I don’t even watch all that much television-by-streaming anymore—I’m at least as likely to watch an episode of the YouTube show Technology Connections, a thrilling exploration of, say, the details of toaster design, than I am to watch Chicago Fire or Tracker, which was apparently the most-watched scripted TV show in the US last season. Way more likely, in fact: I’ve never seen an episode of either linear TV show, but I’ve seen a lot of Technology Connections.

How did my media consumption start to resemble that of a younger person? (Not too much younger: I don’t have TikTok so I can’t pass for an under-25.)

Not to sound jejune but … traditional stuff is boring. It’s aimed at a denominator that’s a little too common. I don’t want to watch what everyone else is watching; I want to watch what I want to watch. And there are algorithms that know pretty well what I want to watch (per YouTube: Norah Jones concert videos and Family Guy clip compilations, both of which are … just about accurate).

There’s an audience, it turns out, for in-depth explorations of old toasters; not enough to sustain a production in the Mad Men era but more than enough to cobble together Patreons and ad revenue now. And I happen to be in that audience.

What’s more, if nobody else is watching the nightly news or starting their day with the local newspaper … I have no particular reason to do so either. Why shouldn’t I just go with the algorithms’ curations?

Partly because it’s bad for me. When I start my Internet browser, I’m fed a pretty steady diet of absolute crap. The browser knows that I will click on extremely clickbaity articles about

Star Trek

Marvel

skyscrapers

fighter jets

widebody jets

Star Trek (yes, twice, but I get a lot of this stuff)

It’s dumb of me to click! I shouldn’t click! I know that the Web site Comic Book Resources is never going to write a good article. But I also want to know who’s in the Fantastic Four trailer!

I feel like my brain is not rotting of its own accord but because its environment is making it as easy as possible for it to rot. There are other factors, to be sure—I don’t really have the time I used to be able to spend sitting down with periodicals (instead, I guess, I write this newsletter). And I definitely empathize with my students’ complaints that they have no attention span; I barely have the attention span to read more than a chapter at a time myself. (Were it not for Audible, my annual book consumption would be trending toward the single digits.)

I have to think: at what point does the exercise of literacy drop enough that you are post-literate?

And I can’t help but think this is bad for all of us—not just individually but collectively. We’re confronted not with a balanced news diet—even if that was sometimes bland—but by devices optimized to serve us cheap sugar highs (“This Marvel revelation will transform everything”—click. I have a Ph.D.!). At this point, I actually don’t know what the right wing is on about half the time because I don’t love my subject enough / hate myself enough to subject myself to their media ecosystem—no, really, you can’t pay me enough to listen to Steve Bannon’s podcast. I used to be able to skim National Review and The Weekly Standard to know what was going on (and be able to pick up on stories that weren’t being covered elsewhere), but … nope, not anymore.

I knew the filter bubble had closed in on me pretty conclusively when I was stunned to see that Trump has net-positive job approval ratings after what has seemed to be three weeks of unimpeded disastrous policymaking. (Concentration camps are losing, 48-52, so there’s that, at least.) Trump’s popular! Most of his individual policies are popular! Is my brain rotten or is everyone else’s—or are all of ours?

Democratic politics relies, in a very fundamental sense, on sharing access to facts for deliberation. Even more important to me, professionally at least, is that our models of democracy assume a public that has access to facts. As Matthew Baum and Philip Potter wrote in 2018, the advent of filters and the Internet means we are in a realm of changes that “short-circuit the process by which citizens can informationally ‘catch up’ with and constrain leaders”—which, they note, might “countribute to instability in foreign policy”. (Yeah, someone might propose seizing Greenland or something.)

I’m in this picture, and I don’t like it.

I feel this. I'm in a different sitch since I don't write about current events, but, like you, even though I have subscriptions to all the usual suspects I don't spend a lot of time with them. In the NYT this morning I can read about (1) Musk's remarks from the White House, and (2) a fact check of Musk's remarks from the White House, and I just cannot be bothered with either. Yes, we are in a dreadful mess in this country, but that means one has to be selective. My reading goes elsewhere, especially book reviews.

Also, fiction is a way to prevent brain rot. Let me tell you about this novel I've found called "Middlemarch"...