Honest Graft and Modern-Day Presidential Libraries

The next four years will see Trump's presidential library become a vehicle for more very legal and very lucrative exchanges

Today, I want to bring you a much more serious piece about political institutions and how they have eroded over the past four years. It's prompted by the recent news about ABC News's $15 million settlement with former President Donald Trump, earmarked for his presidential library-in-waiting—a development that encapsulates the intersection of corporate (not just media) vulnerability, political pressure, and the weakening of U.S. institutions in the contemporary political economy. This case isn't merely about a legal settlement; it represents a broader pattern of institutional decay that will require, at minimum, a generational project to repair.

Just over four years ago, I wrote (gift link) in The Washington Post about the potential abuses that would accompany the development of a Trump presidential library:

With a big war chest, the hallowed "permanent campaign" of the modern presidency could achieve its final form in a foundation dedicated to burnishing Trump's record. Such a foundation could easily generate enough revenue to support endless functions at Trump resorts, hotels and Mar-a-Lago. It could even prove a launchpad for political careers for the next generation of Trumps — or, given that the president would still be in his 70s, for Trump to pull a Grover Cleveland-esque comeback himself.

Some at the time argued (and others have hoped) that Trump won’t have a presidential shrine of any sort because it would be too hard, too expensive, and too complicated. This objection is jejune. Trump doesn’t play by the norms. (A pardon has got to be worth a wing. As for site selection—I’m pretty sure that Florida will be more than happy, one way or another, to have its first library.)

A mature person would simply note this disagreement and move on gracefully.

I told you so! I told you so! I told you so!

Okay, I didn’t get everything right—for one, I thought that Trump would use a presidential library campaign to position himself for a kingmaker role—but I was much more right than the rivals. My key to Trumpology has been to examine whether something is possible and desired by Trump; then to examine whether what stands in its way is norms, money, politics, or ego. If it’s money or politics, then Trump might do it (and make necessary tradeoffs); if it’s ego, he probably won’t do it; if it’s norms, he’ll likely do it just to flaunt his disregard of the norms. It might be crude, amateurish, or garish (or a combination of all three), but eventually, I assume, a president of the United States, clad in immense power, can work his will—find enough supporters and executors to complete a thing. (As a corollary, I assume it will be very hard for Congress to ever actually tell him “no”.)

Well, here we are. News reports show that ABC News has pledged $15 million to Trump’s presidential library to settle claims arising from George Stephanopoulos’s description of Trump’s misdeeds in the E. Jean Carroll case.

A lot of folks are criticizing this as “obeying in advance”, or whatever resistance slogan is deemed to be applicable. As more sophisticated observers, we should be open to the notion that the truth is even grimmer, rather than substituting sloganeering for analysis. Specifically, as an organization that’s part of both the ABC network, which relies on federally regulated access to airwaves (still) to reach its audience, and part of the broader Disney empire, ABC News is vulnerable to federal influence in a number of ways (targeted investigations of affiliates, yanking its access to the airwaves, scrutiny of merger proposals, SEC investigations of its corporate officers, etc). This may not be so much obeying in advance as evidence of hints of blackmail and coercion.

There’s a few points I’d like to make in this regard.

Hardball is here to stay

The Nixon administration’s Watergate arc was toward the (re)discovery of what the Russians would later term “administrative resources”—essentially, the use of federal bureaucracies, including the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Internal Revenue Services, and the security state, to promote the president and persecute his adversaries. That’s why the existence of an “enemies list” was such a big deal—such a list of targets, disseminated through the agencies, could have wreaked real damage to those adversaries without the president ever directly commissioning an act. That is, to skip over many details, how you end up with ex-security state agents burgling the psychiatrist’s office of prominent dissenters or the office of the Democratic National Committee—but the real threat was that the IRS, FCC, SEC, and other agencies would eventually become loyalist, making them tools of the White House rather than the public interest.

The Nixon attempt at doing this was halted mid-arc by public and elite outrage over the rest of the abuses. Fifty years later, it seems plausible that we’re about to pick up where Nixon was leaving off in mid-1973, before all the unpleasantness. This time, however, the political economy of the United States has changed. The country has become much more unequal; wealth has become much more concentrated; and Congress is generally (in my assessment) likely to be more supine than Democrats were when Nixon was president. Separately, generalized trust has plummeted, the news media is tottering on the brink of bankruptcy (and there’s only a handful of organizations left anyway), and other intermediate institutions, like the church or unions, are shells of their Seventies selves. Perhaps most important, the Republican Party is institutionally becoming responsive to Trump II in a way that it was not to Trump I or Nixon.

In other words, as J.K. Galbraith might observe, there’s not much in the way of countervailing forces to stand up against centralizing presidential power. Trump can’t get everything, but he can get quite a lot. The Nixon example—redolent not only of grand abuses of government power but quite normal shakedowns and misuse of official funds, such as the upkeep of the Western White House at San Clemente—suggests that some of what a president so empowered will want will be money.

Presidential “libraries” need reform

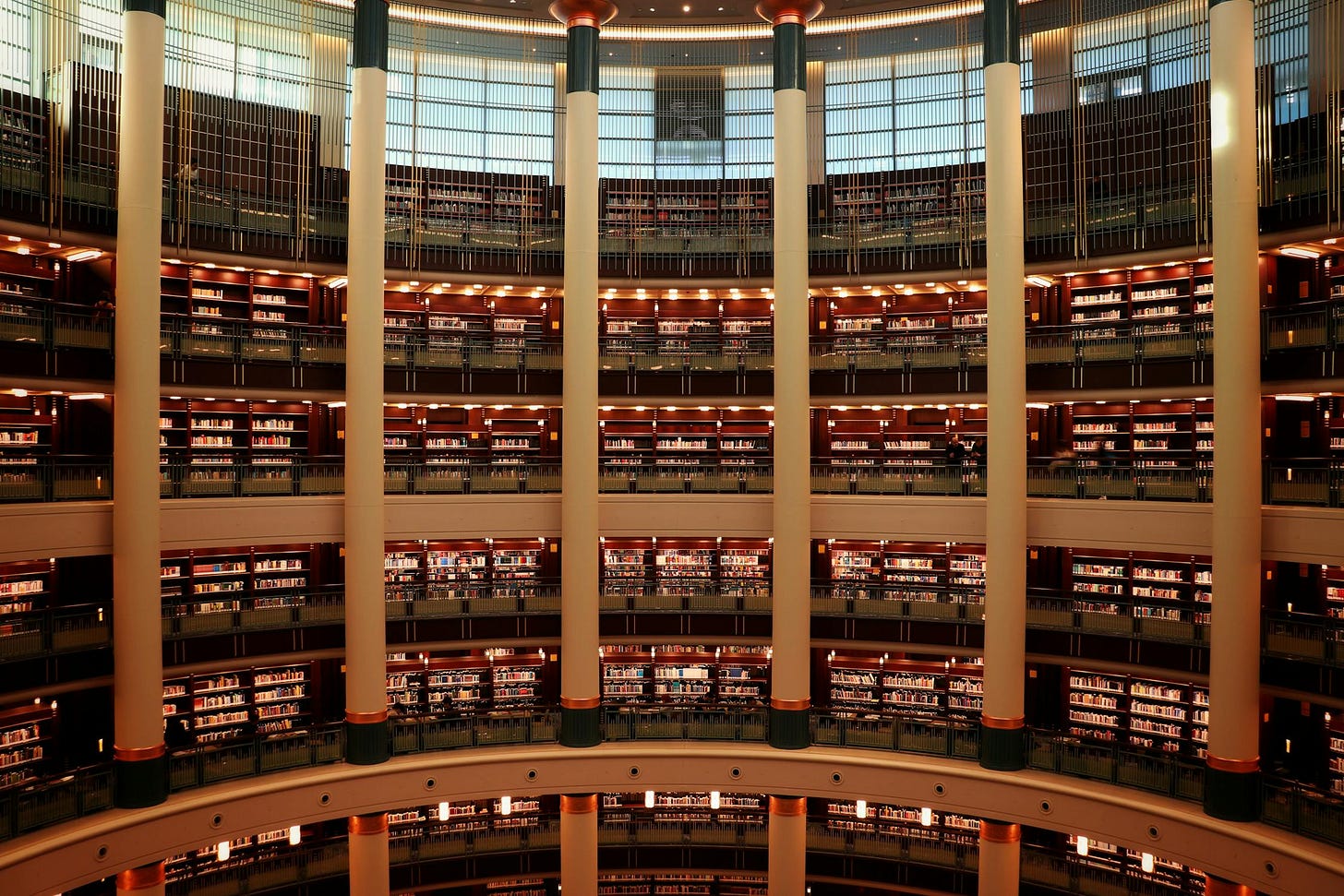

Anyone who’s worked in the field knows that the term “presidential library” refers to a capacious mix of institutions, from private institutions (such as the charming Hayes Library in Ohio) to a state-run institution (the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library) to federal libraries (Hoover through Bush 43) to the post-modern era (Obama and now Trump). (If you’re interested in the background, I cover a lot of it in the Post article linked in the first paragraph.)

The nutshell is that for contemporary presidents, generally speaking, the federal National Archives owns or maintains the papers and artifacts of the presidency, but private organizations build and fundraise for the (frequently impressive) buildings and museum exhibitions. Although the museums may often be operated by the federal government, the federal government is not in the habit of raising millions or tens of millions of dollars for presidential exhibits—after all, the annual National Archives budget is only in the ballpark of $500 million (the short side of that). That means that private presidential foundations, staffed and responsive to presidential families and loyalists, exercise tremendous financial and political pressure over how the libraries’ museums work.

Again broadly speaking, the Obama presidential center (note the shift in verbiage) represents a break with this model. Whereas the “standard” library model involved a combination of archives and museum, the Obama center has—essentially—ditched the archive, in the belief that digitized records can not only supplement but supplant the library side, leaving more space for donor-ready “engagement” and “community” spaces that burnish the Obama legacy. (Given that the center will open in the middle of Trump’s second term, I think there will be some complex discussions among its marketing team about how, exactly, to present this legacy.)

By breaking the link between records and presidential centers, Obama’s decision has created a new model of presidential shrine in which there’s not even a fig leaf of public interest regarding access to the records—the whole raison d’etre of the library system in the first place!

The Trump presidential shrine—and there will be one—will represent this model on steroids. As I wrote back in 2020 (see, I preregister everything):

There are reasons to regret splitting the records from the presidential center. Obama's precedent gives a green light to a Trump center that could be entirely private and free from pressure to ever tame itself even temporarily, as Nixon's library eventually did. Either way, the road is clear for Trump to raise tremendous sums to burnish his reputation. George W. Bush's foundation has more than $400 million in assets ; Trump could probably raise even more from deep-pocketed supporters, small-dollar donors and even foreign governments. (In early 2019, Trump's future chief of staff, then a congressman, strongly endorsed the Presidential Library Donation Reform Act, which passed the House but didn't become law, on the grounds that it would provide transparency in a system vulnerable to abuse .)

With $15 million raised in a single grab, we could see Trump’s shrine make the Dubya center look shabby. Indeed, the 2023 Form 990 for Obama’s center shows that we could be on the cusp of the first billion-dollar presidential foundation (net assets of $962 million by end of calendar 2023).

Trump’s backers are even deeper-pocketed than Obama’s. Why not go for two billion? It’s entirely legal—even tax-deductible—to give to the Trump presidential shrine, after all. And in doing so, there will be lots of opportunities for institutionalizing the America First Policy Institute, a Trump school for rising MAGA activists, and so on—all of which would be entirely keeping with IRS charitable purposes. Imagine the Clinton Global Initiative (to speak of another “innovative” means of turning post-presidencies into brand awareness campaigns) but for making America great forever. (The Carter Center has mostly avoided these issues but I think that it’s increasingly clear Jimmy Carter was something like our modern Cincinnatus, and I doubt that model scales.)

The post-presidency is a problem

The other big essay I wrote in November 2020, when it briefly looked like the Biden team might be interested in strengthening institutions against Trumpism, was about the need to reform the post-presidency in general. My general observation was that as it has become more normatively acceptable for presidents to look forward to decades of post-presidential lucrative activities, the possibility that presidents might trade on their power to placate donors and business partners is rising substantially. This is different to the problem of campaign finance reform, by the way, because the sums we’re talking about for post-presidential activities are much larger and come from many fewer people than presidential campaigns—and, unlike presidential campaign donations, can be used with a modicum of imagination to benefit the ex-president personally.

I think this is an important essay that deserves wider attention (which is not necessarily something I believe is true of every piece of dross I draft). As I wrote then:

As presidents think about how to provide for a legacy project—and a retinue—they will note that current practice not only tolerates but practically encourages raising giant sums from donors, including foreign governments, for such projects. And if it is hard to imagine your favorite recent president shying away from an appointment of a particular agency head or signing a particular executive order based on how it would affect a multi-million dollar gift from a donor, then let the blame fall on a chief of staff or aide or some other actor who might make such decisions without consulting the president in the misguided belief that they are just doing what the boss wants. The effect is the same—or, to be as generous as possible, the suspicion of the effect is the same.

Generally speaking, the effect of having presidents who can look forward to themselves and their dynasties enjoying the spoils of office for decades is a genuine problem for policymaking. The solution I propose—explicitly curtailing and channelling post-presidential enrichment—seems like the ultimate goo-goo reform, and maybe it is. I prefer to think of it instead as a form of Coasean bargaining in which we as a public purchase post-presidential enrichment streams in a lump sum—and receive in exchange some measure of more honest government. Not goo-goo: pragmatic accommodation in the form of recognizing realities, adjusting to them, and creating penalties for nonperformance. Think of it as a presidential NIL.

Summing up

Our long national nightmare is just beginning. Our Constitution doesn’t work. The current state of presidential libraries and the post-presidency more generally shows how even the updated, mid-20th century version of constitutional norms have failed to keep pace with the practice and perils of contemporary wealth inequality. At some point—maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow—we will need to address these, and we may as well work hard to identify the problems and fix them now.

Been a while since I visited the Musgrave Orchard. As even you admit, not all trees are created equal. There is the occasional crab apple. Today's ("Honest Graft") was golden. Delicious. Stunning how in 48 hours you turned around the story of ABC News coughing up $15 million for allegedly smearing Trump on a rape charge into an illuminating - and alarming - wake-up call on Trump's methods for enriching himself and further corrupting the purpose of presidential "libraries." Call me shallow but my favorite line of the column was, "I told you so! I told you so! I told you so!" In fact, it is was so delicious, feel free to bust out with a white-man moon walk (but please spare us the video).