I’m Paul Musgrave, a political scientist and writer. This is Systematic Hatreds, my newsletter about my thoughts regarding politics and the study of politics. The newsletter takes its title from a line in The Education of Henry Adams:

Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, had always been the systematic organization of hatreds.

This week, we’re talking about the politics of video game violence in an era of real war.

Games of War

The TOS-1 Buratino is a Soviet-developed multiple rocket launcher that can deliver two dozen unguided thermobaric rockets up to twelve kilometers. Those rockets, capable of vaporizing humans and causing unimaginably painful death, are weapons of terror that Russian forces are allegedly deploying at this moment in Ukraine.

It’s also a 140-point vehicle that can occupy two slots in the support tab of a REDFOR deck.

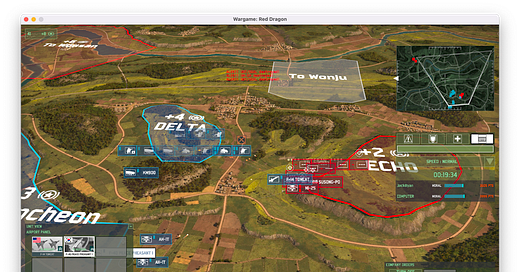

Let me explain. For the past eight years, I have been a devoted but relentlessly casual devotee of Wargame: Red Dragon, a fiendishly complicated real-time strategy game that simulates tactical conflict among late Cold War-era militaries. One consequence of the (mumbles) of hours I’ve spent playing the game is that I recognize almost all of the vehicles engaged in the Ukraine war … or, rather, their video game equivalents.

In real life, the Buratino is basically a war crime on wheels. (On tracks, rather.) In Wargame, it’s a showy area-denial weapon that can be incredibly useful in clearing urban positions of entrenched infantry.

For most of my youth, American society was gripped by recurrent waves of a moral panic regarding violence in video games. Video games, politicians and scolding researchers said, would desensitize those who played them to violence. Many blamed the Columbine shootings (and the many other school shootings of my youth) on video games turning wayward teens into cold-blooded killers.

I used to think that was silly. Well, okay: I still do. But I do have to wonder whether there isn’t a kernel of truth—just not about behavior but about perspective.

Wargame simulates combat at the level of a single battlefield. It’s not a first-person shooter; players are in control of many units, not just their own. It’s also not a fully strategic or integrated universe: unlike in say Civilization, players don’t have to manage an economy or diplomacy. It’s realistic, or at least realist-ish: you can’t “level up” units from one stage to another (an F-14 Tomcat can become more experienced, but it can’t be improved into an F/A-18 Hornet).

For a game about the experience of combat, it’s strikingly distant from actual people. Yes, every vehicle has a driver, pilot, or commander with a name—but that name is only revealed after combat has ended, when you read about the other characters they killed or the experience they gained. Perhaps most tellingly, in Wargame, there are no civilians. Not in the cities, not in the forests, not in passenger airlines inadvertently flying over a combat area to be downed by a Buk anti-aircraft missile (Buk launchers: 70 pts).

Wargame is a zone of war fantasia. It resembles the real models of the real thing in the same way that schematics of the battlefield resemble an actual battlefield: both not at all and in an incredibly compelling way. In those schematics, there are no politics or laws of war, no uncertainties that can’t be managed and no ethical dilemmas: just technical problems to be solved, ideally through a combination of skill and more expensive toys.

As a game, Wargame is shockingly educational. Spending too many hours watching airplanes fall prey to anti-air fire led me to understand the importance of suppression of enemy air defenses. Reading The Hunter Killers, a history of American pilots who flew missions in the Vietnam War to hunt and destroy anti-aircraft missiles, felt like a recapitulation of learning tactics I’d developed (poorly) against pretty much the same range of Soviet bloc weapons—and the counter-tactics I learned in operating anti-air batteries against enemy aircraft. (For fellow devotees: you’ve never seen me online; I’m too much of a filthy casual.)

I’m a professional student of international relations, a subject inextricably bound up with violence between militaries. (The title of this newsletter suggests something about what I see as the organizing principle of politics.) In that regard, the mumbles of hours I’ve spent playing Wargame has been educational. I have a much better idea about why urban warfare is bad, why you should never send tanks into a city, and why the introduction of specific new weapons can upset the balance of a given battlefield. That sort of learning by doing is incredibly seductive.

It would, of course, be stupid to confuse Wargame for real war. Yet when you’ve invested mumbles of hours in a game, it seems like the real thing. The feeling of recognition I had when reading about F-105 pilots inventing the Wild Weasel anti-anti-aircraft mission over Vietnam was real: I, took have killed SA-2s, and I, too, have been shot at by Strela missiles shot by soldiers hidden in jungles. Except that I haven’t. And I didn’t have to spend a decade as a prisoner of war after being shot down—or die when an anti-radiation missile slammed into my radar installation.

By the same token, Wargame taught me that a Buratino was a useful way to coerce an enemy from a stronghold. And when I saw the footage of the units moving across the border, I felt a sinking feeling in my stomach, because on one level I knew what could happen—what is about to happen.

Wargame centers the perspective of the weapons, but that’s not what’s important. What matters are the consequences and contexts of the weapons. In Wargame, there are no civilians hiding with their dogs in underground shelters, terrified of a Buratino or a Grad or a Uragan striking their position. In real life, what else matters?

The perspective of Wargame is the same as the perspective of pundits and Carol Cohn’s defense intellectuals. Talking about great games and power plays reduces conflicts to the player’s-eye view of the battlefield. It’s a tempting perspective, one that makes power and influence look like all there is. It’s kin to the curated “war through a straw” perspective of the embedded U.S. journalists of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, or the drone videos of the war on terror that showed “squirters” and Hellfire strikes (which played differently on YouTube than for the men and women who viewed them live as they piloted the UAVs and launched the ordnance). If you’re not in a war or a veteran or one, it’s probably your perspective.

Yet those perspectives are far from those of the shaky phone videos of aircraft launching missiles at houses with children inside or security camera footage of rockets hitting apartment buildings. There’s a reason game designers don’t include those perspectives in entertainment. And there’s a reason I won’t be playing Wargame again for a long time.

Thanks for sharing.

I feel like there’s a way to conceptualize video games like this as part of the war itself. Instead of viewing Wargame as a simulation of the Cold War, might it also be a subset or extension of it? An aspect of its ritualization? Maybe, now more than ever, IRL-war-based video games are simply a new dimension of the actual conflict.

As someone who spent more time in my 20s than I’d care to admit on the Civ and Total War franchises, I feel seen but also tempted to give this thing a go. Fun, thoughtful read.