About Systematic Organization

I’m Paul Musgrave, a political scientist and writer. This is Systematic Organization, my newsletter about my thoughts regarding politics and the study of politics. The newsletter takes its title from a line in The Education of Henry Adams:

Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, had always been the systematic organization of hatreds, and Massachusetts politics had been as harsh as the climate. The chief charm of New England was harshness of contrasts and extremes of sensibility—a cold that froze the blood, and a heat that boiled it—so that the pleasure of hating—one's self if no better victim offered—was not its rarest amusement; but the charm was a true and natural child of the soil, not a cultivated weed of the ancients.

This week, we’re talking about how violence has formed a key part of U.S. politics throughout its history. It’s not that “it can happen here”—it’s that it has. Repeatedly.

Domestic Violence

Some discussions on Twitter brought to light the fact that even well-informed political scientists may see political violence as peripheral to American history, not as a force that’s shaped U.S. society.

I don’t mean the familiar (and important) topics of big, structural violence, like slavery or the seizure of Native lands—I mean the acute combinations of private and public violence aimed at social control and even overthrowing governments that we would recognize if, as the cliche holds, “you saw it in another country.”

I mean widespread lynchings, including the 1871 killings of several Chinese immigrants in Los Angeles or the 1930 Marion, Indiana, lynching that was the last such in “the North” but which still had a survivor in the 21st century. And I mean coup attempts that tried—or succeeded—overthrowing elected governments and replacing them with unelected regimes.

White America and official America—but I repeat myself—tell these stories obliquely. There was a whole vocabulary for talking about them: “race riots”, for instance, whereas elsewhere we would have deemed events like the Tulsa massacre as pogroms or, well, massacres.

That’s if they were talked about at all. I mention Tulsa because I’m sick of people talking about the Tulsa massacre as an “as seen on TV” event (the TV show in question being Watchmen).

This is irrational because I’m glad (well, for certain values of “glad”) that people know more about this, but I’m upset that it took a prestige TV show to bring this knowledge to the “mainstream” discourse. And now “Tulsa” stands out as something exceptional when it was actually not quite exceptional but rather just a notable attack among many such pogroms at the time.

I learned about Tulsa and other violence in U.S. history long ago, when I was writing my senior college thesis and what would become my first article, which detailed the formation of vigilante groups across Indiana to resist bank robberies in the 1920s and 1930s.

This impromptu course in the history of American violence took me well beyond Indiana in the 1920s. It stretched from the Carolina “regulators” of the 18th century to the San Francisco vigilance committees of the 1850s to the use of private violence by the Klan in the 1870s to other massacres. Through this, I learned much about the ordinary brutality by which American laborers and minorities were kept within bounds.

I distinctly recall learning about the slaughter of Black people in Elaine, Arkansas, in 1919. I remember this because 200 Black people were killed, but I’d never heard of it. And I was so confused that the only places I could find in the vast Main Library at Indiana University that described it were mimeographed journals of Black history from the 1970s.

So isolated were sources about this atrocity that for a time I entertained doubts. Could this alleged massacre be real? I wondered. If it was real—if 200 Americans had died violently at the hands of their neighbors in the middle of the 20th century—surely this would be better known and remembered.

Surely it would have been in my history books. All the important parts of history were in the textbooks. That’s what I was told, at least.

I would later realize that the killings of the Black farmers and families in Elaine was the sort of violence that scholars of the Rwandan genocide and the Holocaust would be familiar with: brutal, neighbor-slashing-neighbor stuff.

And it happened here.

And it’s still not well known.

Maybe Watchmen can fit it in the third season. There’s enough similar stories to last for many more seasons to come.

This classic painting from the American series The Course of Empire shows violence as a hypothetical, a punishment for wickedness, not a recurring feature of “normal” American life or anything to do with race.

Learning about Elaine, and Tulsa, and many other instances that weren’t in my textbooks did more to convince me that the textbooks were cheerful propaganda than any exposure to Lies My Teacher Told Me.

And so even those of us who were White and grew up in communities where such attacks had taken place don’t have much of a frame of reference because these incidents aren’t included in official sources.

In 1903, for instance, Evansville, where I grew up, was wracked by a race riot. It followed a traditional script: a White man murdered by a Black man; the lynch mob visiting the jail to seize the murderer and kill him; a pitched battle between the mob, armed Black men, and finally the Indiana national guard; and then dozens more people left dead and wounded afterward.

This must have been a searing, scarring incident in the city’s history. It must linger even now in the consciousness of Black Evansville. It was a footnote in the city’s history for me, a dimly recalled half-detail about the former county jail across from my father’s office in the center of Downtown. We didn’t do units about this in school, and it’s not (or at least it wasn’t) something solemnly commemorated annually. You had to search out knowledge about it (and my googling for this email confirms it’s not easy to find).

So much of the history of this country is inconsiderately at odds with the official narrative. And political scientists who have mastered the orthodoxy may find themselves unable to wrestle with the facts that lie outside the textbook catechism’s bounds. Drawing stylized facts from the happy Whig history of the country, they hide simple dynamics—the searing brand of the color line—behind complex theories.

Given our political temper, maybe it is best to highlight some episodes that should be as familiar to us all as any other bold-face terms we had to memorize in tenth grade. Let me move that needle a tiny bit by bringing to light four cases from U.S. history that I think are misunderstood or not enough well known. It’s better for all of us to be on the same page when we talk about the past and how it informs our evaluations of the present.

1874 Coup Against Louisiana

In 1874, a militia group called the White League overthrew the government of Louisiana. Its 1,500 members were upset that the state’s post-Reconstruction government was corrupt but mostly that it was racially progressive (the lieutenant governor, Caesar Carpenter Antoine, was Black). The group, organized by former Confederate officers, killed at least 13 police officers as they assaulted the state government. Three days later, the government was restored by the order of President U.S. Grant and the U.S. Army.

This isn’t a happy story. It wasn’t the first instance of large-scale violence in the state after the Civil War. In 1866, dozens of mostly Black Republicans demonstrating to receive the right to vote were massacred by White Democrats. In 1868, 200 Black people living in Louisiana were killed by Klan members over the course of weeks in an effort at voter suppression and simple terrorism. In 1873, as many as 150 people, almost all Black, were killed in Colfax, Louisiana, in violence stemming from the 1872 Louisiana elections.

And during this period constitutional government was hardly functional in Louisiana. A disputed gubernatorial election in 1872 was marred as both sides claimed victory. The election dispute was eventually settled by the federal government. In 1873, P.B.S. Pinchback—the first Black governor of a state, who succeeded after an impeachment and removal, and also a wheeler-dealer of the Gilded Age type—was elected to the U.S. Senate but was blocked from taking his seat.

In this context, the fraudulent 1876 election seems a lot more normal.

1898 Coup Against Wilmington, North Carolina

In 1898, a group of armed White people overthrew the recently elected local government of Wilmington, North Carolina and replaced it with a less racially tolerant one. This was, literally, a coup: the White leaders confronted the mayor, council, and police chief, forced them at gunpoint to resign, and replaced them with a new, unelected government. Along the way, they burned down a local newspaper printing office and murdered 60 others.

The armed group justified their efforts in terms they were sure would find a supportive audience: they were just trying to uphold white supremacy. They accused the North Carolina “fusionist” movement uniting Populists and Black Republicans of upsetting the post-Reconstruction racial order. And for decades that was how the Wilmington massacre was remembered.

A 2017 article in The Atlantic (which wrongly calls this the “only coup d’etat” in U.S. history—it may be the only successful one) records the events and the history of its coverup and, excuse me, white-washing. It also mentions that the Wilmington massacre was part of a state-wide coordinated effort to shut down Black newspapers across North Carolina.

1919 Massacre in Centralia, Oregon

There are many labor stories I could fit into this history, but I’m choosing to highlight this one because I think that the post-World War I wave of labor repression is too little known. McCarthyism and the post-Second World War Red Scare are familiar topics, but the Palmer raids and the violence against labor movements (and sometimes by laborers against capital, police, and Pinkertons) is all but forgotten from the official perspective.

On the first anniversary of the Armistice, the town of Centralia, Oregon, held a parade for American Legion members. It turned into a gun battle and lynching. Veterans and other citizens marched on the local headquarters of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or Wobblies). This was a real battle: four of those who died were veterans. But the violence continued as a mob later lynched an IWW member (himself a veteran) in retaliation.

This was part of a wave of violence between labor and other groups. Conservative groups, including the government but also independent organizations like the Legion, took part in reactionary violence against unionists, socialists, and Communists out of fears that they might produce a revolutionary movement in the United States. Extreme labor organizations themselves employed violence. The Great Steel Strike of 1919 involving 350,000 workers around the country would also lead to the deaths of at least 18 people.

And the scale of the labor unrest as the economy lurched from wartime to peacetime was vast, with huge strikes afflicting the entire country. One such strike, by the Boston Police Department, made the name of an unremarkable Massachusetts Republican governor, Calvin Coolidge, who broke the strike and used it to catapult himself to the vice presidency.

1995 Attack on Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building

The bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building on April 19, 1995, killed 168 people. Attributed to Terry Nichols and Timothy McVeigh, who used a rented Ryder truck full of an ammonium-nitrate fertilizer as a bomb, the attack echoed the white-supremacist tract The Turner Diaries, which depicts a similar attack on the FBI Building.

As Kathleen Belew, a University of Chicago historian, described in testimony before a House committee, the attack mirrored the logic of violent anti-government, white-supremacist terror groups’ strategies for carrying out terror attacks while denying the government easy means to build a prosecutable case. This strategy, known as “leaderless resistance,” evolved in the 1980s as a way to carry out the white-supremacist movement’s anti-federal campaign in the service of creating a White homeland (at a minimum).

Such violence and tactics fit uneasily within simple political motivations, like polarization and partisanship. Rather, it looks very much like the motivations of groups like al-Qaeda and ISIS who seek social transformation and political control through armed violence. And as Belew and others have argued, the idea that McVeigh was a lone wolf (or a wolf working with Nichols) seems unlikely given the sophistication of the plot and McVeigh’s own entanglements with the rest of the white-supremacist world.

What I’m Reading

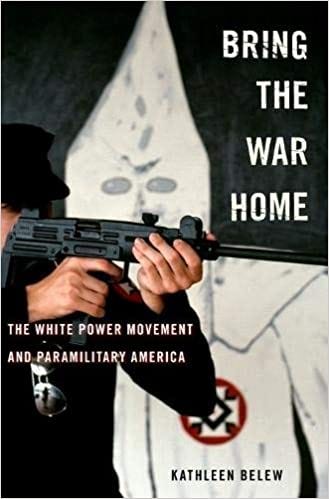

This week, I’ve been reading Kathleen Belew’s Bring the War Home.

This is a carefully written book that argues that violent white-supremacist groups were mobilized by the Vietnam War and the Cold War more generally to undertake an armed campaign in the service of their anticommunist, White supremacist goals.

In particular, Belew argues that the Vietnam War served as a dolchstoßlegende—a “stab in the back legend”—akin to that which the Nazis claimed as justification for their own movement in the 1920s. Anti-communism could have worked, they claim, had White soldiers not been let down by pusillanimous leaders in Washington.

Such commitments motivated them to harass and torment Vietnamese refugees in Texas and eventually to launch a deadly attack on (Black) Communist groups in Greensboro, North Carolina. Combined with the skills and weapons the groups acquired from their service in Vietnam and their ongoing connections to military members, these groups became much more frightening than we may recall now.

After the end of the Cold War, the demise of Communism left these groups hunting for a new enemy, and they redoubled on the federal government. Belew persuasively argues for the 1995 Murrah building attack as a culmination of this strategy.

Belew’s work suggests that armed violence by militant movements is a far more enduring and deep-rooted part of American politics than conventional understandings admit.

Support My Students

If you can, please give to support students in my Politics of the End of the World class as they prepare podcasts exploring the politics of the apocalypse.

The amount of information that needs to be just flat out ignored to make people believe in American Exceptionalism really is jaw dropping. The only thing exceptional about America is how many murders (domestic and abroad) we are willing to condone just to make a few billionaires even richer.