Did Khrushchev Like Pepsi? An Investigation

What goes into establishing even a little detail in a bigger story

I’m Paul Musgrave, a political scientist and writer. This is Systematic Hatreds, my newsletter about my thoughts regarding politics and the study of politics, named for a line in The Education of Henry Adams:

Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, had always been the systematic organization of hatreds.

This week, we’re talking about my new article in Foreign Policy about the saga of Pepsi’s attempts to conquer the USSR—and how it briefly ended up owning 17 rusted Soviet submarines.

Did Khrushchev Like Pepsi? An Investigation

This weekend, Foreign Policy published my (generously) longform article about PepsiCo’s long attempts to pry open the markets of the USSR. (You should go read it!). In any article this long, of course, a lot ended up on the cutting room floor—and deservedly so: this wasn’t the time to write the definitive Wheel of Time-length exposition of the details of East-West countertrade through the lens of a Pepsi bottle.

But you all have signed up for my newsletter, and so you get to see a little bit more of how the sausage (or sosiska) is made.

With the Pepsi story, as with its predecessor the (post-Soviet) Mikhail Gorbachev Pizza Hut ad story (which if you haven’t read, well, you also should), I had two goals.

The first was to situate these notorious incidents in a broader context. One thing I learned from reading collected volumes of Stephen Jay Gould is that weird or bizarre incidents usually have a perfectly explicable background—they’re just easy to pluck from that context and serve as free-floating referents for weird stuff. The Pepsi Navy story has definitely suffered from that fate, as the factoid that Pepsi “once owned the Nth-largest navy in the world” has been stripped of basically all of its context and turned into a fun fact that some content mongers can spin into YouTube videos that garner more than a million views (which will net them a few hundred or even a couple of thousand dollars). As an international relations scholar, I wanted to put these incidents in the context of world politics—and, while doing so, to convey some of the basic factual and analytical information that I’ve found that many to most Americans (and practically all younger Americans) lack.

The second was to clean up these stories and put the definitive (or at least a vastly more accurate) account out into the wild. Most of what you will read about the Pepsi Navy is, basically, copypasta (although two or three earlier writers had done a little more digging). The ur text for almost all of the many rewrites of the story was a Flora Lewis column in the New York Times from 1989, which seeded the story likely for two reasons: it’s at the top of Google sources and, just as nobody ever got fired for buying IBM, nobody ever got faulted for trusting the New York Times. Yet as the story got rewritten and rewritten, the basic details kept mutating and getting farther and farther away from the source. Some parts were accurate, but even the accurate parts were being buried in a story that didn’t really hang together.

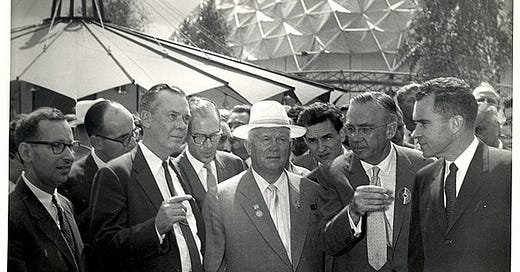

One temptation that writers who aren’t paid very much or edited very closely have is to throw every little cool thing that they find that seems relevant into their story. It pads word count and—more important—to audiences that themselves aren’t reading very closely it adds verisimilitude. In other Internet writing about the Pepsi Navy, for example, you’ll see references to Pepsi’s Michael Jackson commercial in the USSR (the first ever Western commercial to air in the USSR—but not the first television commercial on Soviet TV). Why? Well, because it’s a cool thing you’ll learn about as you google pepsi soviet submarines 1989 and related keywords. (Trust me.) And if you’re contracted for 800-1000 words, why not take the search you’ve already done and turn it into 50 of those words? The same with Donald Kendall’s quip about how Pepsi was disarming the Soviet Union faster than the U.S. government (from the Flora Lewis column) or Kendall’s relationship with Richard Nixon at the 1959 U.S. exhibition in Moscow, where Pepsi was first served in the Soviet Union (also, you guessed it, described in the Flora Lewis column).

When so many anecdotes can be traced to a single text, or a handful of them (a now-paywalled 1992 Los Angeles Times retrospective on the deal also helped some of the more diligent Internet writers), then, to the careful researcher, it’s a little bit of a danger sign. Single sources lie, exaggerate, misremember, cheat, and omit. Getting a handle on the past ideally requires several different sources.

So let’s go back to the subject of this newsletter: did Khrushchev like Pepsi? Here’s how Lewis (apparently sourcing her anecdotes from Kendall personally) told the story in 1989:

A cheery, white-haired, extravagantly energetic 68-year-old, Mr. Kendall is also a truly imaginative businessman. In 1959 he set up a stand at the American exhibition in Moscow. Nearby was a kitchen equipment stand, where Nikita Khrushchev and Vice President Richard Nixon got into a famous debate.

It was literally, as well as figuratively, heated. When Mr. Kendall noticed the Soviet leader wiping his brow, he rushed over with a nice cold Pepsi and was rewarded with a unique, unpaid commercial for his product, published round the world. Mr. Kendall followed up with a deal obtaining exclusive rights to the Soviet market in return for exclusive distribution rights for Stolichnaya vodka in the U.S.

This is a neat, earnest story. It does violence to history, of course (the Pepsi-vodka swap wouldn’t be arranged for more than a decade later). It overlooks Kendall’s own story told elsewhere about what the connection to Nixon was (Kendall and Nixon had apparently planned to get a Pepsi in Khrushchev’s hands the night before, according to a story the ebullient, and I think probably frequently exaggerating, Kendall told a later Timesman). It doesn’t explain why Kendall needed the Pepsi-vodka swap in the first place (the Soviet ruble was not convertible, so bartering was the only way to arrange commercial transactions). And it doesn’t explain why the Soviets would be interested in such a trade in the first place (a story involving PepsiCo’s prestige, Kendall’s patronage of Nixon, Soviet favor-currying with the U.S. president who had been a PepsiCo lawyer before winning office, and a broader drive to open Soviet trade to the rest of the world).

I’m not trying to be (too) critical of Lewis here: her column is clear, concise, and interesting, and generally holds up. Two paragraphs written on deadline about a tertiary point should not be held to the same standards as a dissertation. But when those paragraphs end up inadvertently shaping how a later generation views an entire episode, it’s a good idea to start taking them apart.

Interestingly, though, Lewis doesn’t mention if Khrushchev liked the Pepsi.

Other sources are divided. One 21st-century source concludes “Khrushchev delighted at the sugary, fizzy drink.” Atlas Obscura argues instead that “Khrushchev’s son later recalled that many Russians’ first take on Pepsi was that it smelled like shoe wax.” Delight and shoe wax seem like pretty opposite reactions! Yet there’s no particular reason to give credence to either one. Even Atlas Obscura’s sourcing of a recollection to professional rememberer Sergei Khrushchev, although far better than citing nothing, is not exactly dispositive.

One way to settle debates like these is to try to get the best evidence possible—close to the source, reliable, and told by informants with no agenda (or, even better, who are making admissions against interest). By the way, one source of slant can be other writers’ interests in having a good, clear story—it’s much easier to say that Pepsi broke into the USSR after its leader delighted in Pepsi than to explain how shoe wax-tasting beverages ended up with a monopoly on trade.

So off to the Time magazine archives to see what their reporting was. Time chronicled Nixon’s visit to the American National Exhibition in Moscow extensively, and its report has the kind of useful asides that tell even more than the journalist who wrote it may have thought. For instance, consider this paragraph:

The two first met the morning after Nixon arrived in Moscow. In a black ZIS limousine he was whisked to the Kremlin for a call on President Kliment Voroshilov, the figure head chief of state, and then on Nikita Khrushchev. In Khrushchev's office began a running debate that lasted, on and off, into the evening. Khrushchev started it by complaining fiercely about the Captive Nations Week proclamation, U.S. overseas bases and restrictions on U.S.-Soviet trade.

Catch that? Sure, there’s a lot of Cold War boilerplate denouncing of U.S. foreign policy positions—but there’s also a denunciation of restrictions on U.S.-Soviet trade. Khrushchev wanted trade with the Americans! An enormously useful article in Congressional Quarterly from 1959 laid out Khrushchev and other Soviet leaders’ campaigns to lift export controls from the USA to the USSR, as well as US officials’ reluctance to do so: “In the first quarter of 1959 the Commerce Department refused licenses for shipments to the Soviet Union valued at about $15 million; licenses were approved for only $376,-000 worth of exports to that country.” (The concerns, as ever, were about dual-use technologies, but also about politics—it was hard to lift trade restrictions after one crisis after another in the seemingly endless series of 1950s Cold War crises.) For Khrushchev’s emphasis on this point to have risen to the level of the Time glow-up on Nixon’s visit suggests that trade was very much on the Kremlin’s agenda.

The careful Time piece records only of the Pepsi episode that “ Khrushchev took a skeptical sip at a Pepsi-Cola” (emphasis added).

The New York Times’s Harrison Salisbury, by contrast, gave several column inches to the Pepsi encounter in a July 29, 1959, article headlined “Cola Captivates Soviet Leaders.” Describing the Soviet premier’s entourage as “cheerfully quaffing” the drink “with pleasure” and quoting Khrushchev as exclaiming “Very refreshing!”, Salisbury’s article contradicts Time’s account. Robert Healy of the Boston Globe also came down on the “very refreshing” side (“The only concession was made to Pepsi-Cola. Even Khrushchev said this was very refreshing,” he reported in the August 2, 1959, edition.)

And that is…more or less it. Three pieces of original reporting, two to one in favor of “very refreshing”, plus the recollections of Sergei Khrushchev, which I think we should accept with a steep discount—but which are also pretty strong feelings!

So why did I go with Time’s “skeptical” verdict?

The answer has to do with what it means to weigh evidence. (And let’s pause to acknowledge that this is a choice of one adjective that doesn’t affect the narrative of the story I was telling that much.)

Khrushchev had motivations to say how much he liked the soda. He was angling for trade—mostly he wanted heavy industry (entire factories!) but he also wanted consumer goods. And Khrushchev wanted to argue that the Soviet Union would catch up to American standards of living soon—that was the whole basis of the argument in the kitchen debate. But that didn’t mean he would like the soda.

The American reporters had conflicting motivations. Saying that Khrushchev (and other Soviets) liked the soda would be a way of signaling that the American way of life was better than the Soviet one—and that everyone knew that. On the other hand, saying that Khrushchev didn’t like it would help portray him as combative. On balance, however, the former motivation is more likely to fit with great storytelling.

Furthermore, not all journalists are created equal. And that was the clincher for me: I don’t trust Harrison Salisbury as much as others. As even Salisbury’s Times obituary stated,

Some of Mr. Salisbury's fellow journalists whispered that he sometimes exaggerated in his reporting. He had a nearly boundless confidence in his reporting and intuitions, one that would sometimes lead him to conclusions that, given his larger-than-life personality, few editors at the time dared challenge.

Frankly, Salisbury’s “Cola Captivates” piece is too breezy, too committed to its thesis, and too stylish. Every piece of evidence points to the same neat storyline: Soviet leaders’ propaganda line against cola drinks vanishing after a single sip. I mean, maybe! But I’m doubtful. And it’s too good of a story. (As for the Healy mention, I dismiss it because it’s a single line in a longer article without much evidence—and it might well have been passing along Salisbury’s own story.)

So, on balance, I’m convinced: Time (and Sergei) were right. Khrushchev didn’t like Pepsi. He may well have said he liked it (or, technically, preferred the version bottled in Moscow to that bottled in the USA), but it’s doubtful that meant very much. Shoe wax it is.