Biden/Trump Isn't Ford/Nixon

Swatting down the dumbest argument about the current troubles

Many people are arguing that President Biden needs to stop the investigations—prosecutions!—into Donald Trump’s various offenses against state and federal law. One variant of this strain is particularly silly: that President Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon should serve as an honorable example for President Biden about how to shut down prosecutions.

Anyone making this argument seriously is unworthy of your time and you will save a great deal of your life and effort by refusing to listen to them henceforth on any issues. The Ford/Nixon situation could not possibly be further from the Biden/Trump situation.

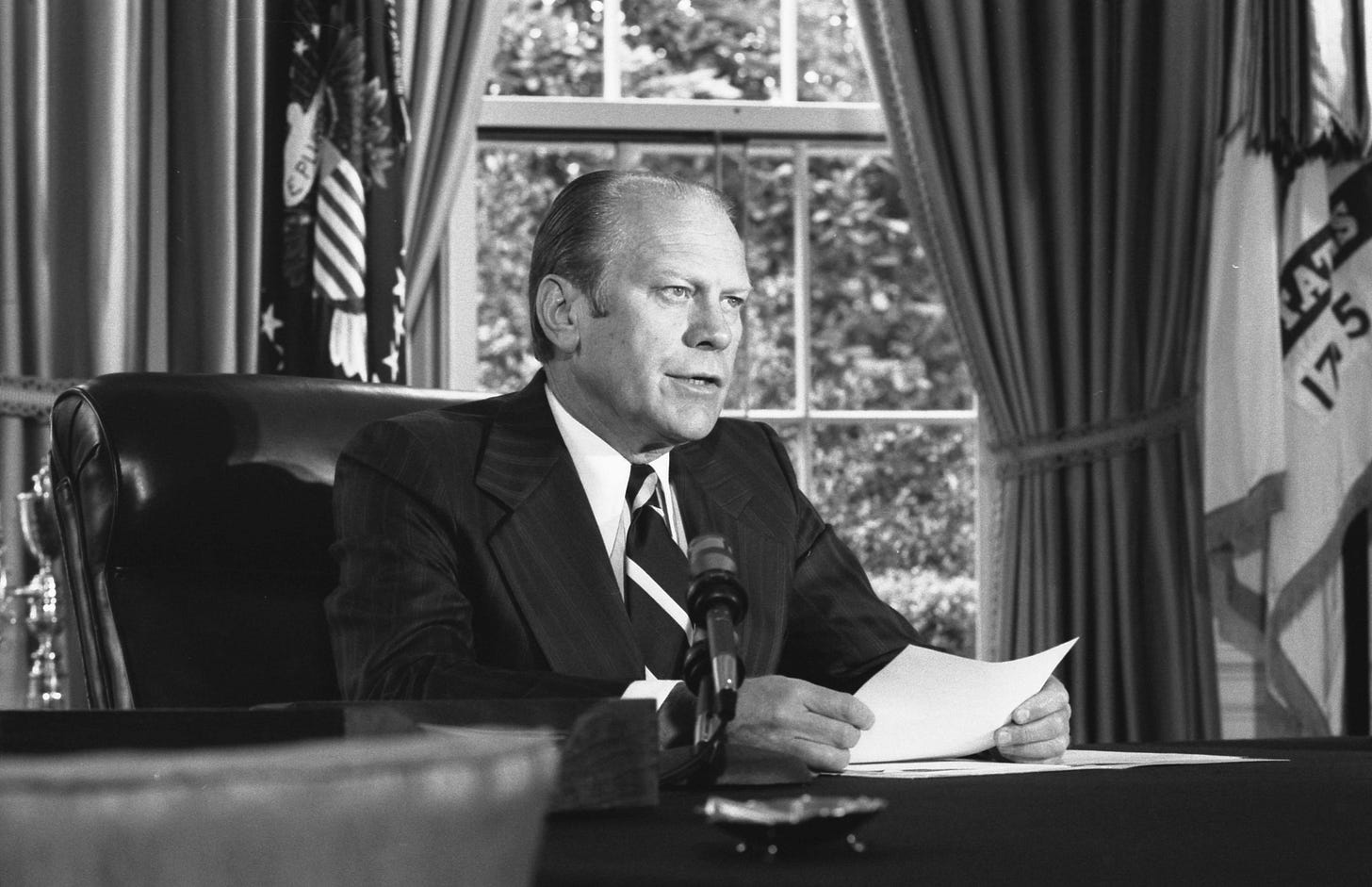

To recap. Gerald Ford was vice president when Richard Nixon resigned, and as Nixon was entering a state of disgrace (Missouri), Ford became president. A month later, Ford pardoned Nixon.

The pardon was controversial at first. Over subsequent decades, leading American elites—including the Kennedy clan—came to celebrate the decision, even giving it the Profiles in Courage. By doing so, elites ratified Ford’s own justification of the pardon, in which prosecution of Nixon would be unfair given the consequences he had already suffered and could raise ugly passions, and second they also cemented a norm that politicians would suffer comparatively minor consequences for abuse of office. (Nixon didn’t got to prison, although many of his senior aides did for acts he commissioned or tolerated.)

Those who urge President Biden to follow the alleged precedent here are disingenous, misinformed, or misguided. They do not account, or ignore, for the fact that even Ford’s sweeping apology for Nixon was ultimately based on political and legal calculations that are strikingly different from those attaining in the Trump case.

(Let me pause here by saying that Ford’s pardon message is bizarre—much more bizarre than I remembered it. Nixon’s troubles, Ford said, were “an American tragedy in which we all have played a part”—what the hell, Jerry, I didn’t order a break-in of the Democratic National Committee! Its extreme solicitousness for Nixon’s well-being goes far beyond what a normal amount of national healing would require; it even, in my judgment, exceeds what the dead-end Nixon supporters needed—and Ford, as a political animal, was probably, even if instinctively, anticipating the 1976 primary fight in which his right flank was exposed. Rather, I think the document reads best as if it’s addressed to an audience of one: RN himself. And that does suggest that part of the pardon was a bargain in which Nixon would just go away. )

Those calculations were twofold. First, Ford himself wanted to get away from the Nixon era as fast as possible, and pardoning the ex-president would be one way to do so. To be sure, this was a risk, and it didn’t pay out, as Ford would lose re-election to Jimmy Carter. Nevertheless, it was probably the canniest political play available to Ford, as at a minimum it gave him two years to build his own case and, further, may have bought at least a little omertá from his longtime associate.

Second, however, there was the fact that Nixon, by resigning, had made himself a nonentity. The man who had already made so many comebacks couldn’t come back from the fact that he was ineligible to seek the presidency again, even if his incredibly low popularity made that unlikely. Indeed, Nixon had already been hounded into resignation to avoid impeachment and removal—in that regard, Ford had been right earlier: the system had (belatedly) worked to remove the cancer on the presidency.

It should be clear that neither of these calculations apply to the Biden/Trump case. Trump is not out of the picture: he’s in the center of it. Three years into the Biden administration, Trump remains the enter of gravity for American politics, as he has been almost ceaselessly since he descended the golden escalator at Trump Tower. Trump has not suffered any consequences from his actions: his (second) impeachment went nowhere, and all that’s happened is that he’s been charged. He remains someone with a very good chance—the best chance, but one, of any individual American—of being president in 2025.

So where does this metaphor get its oomph? Why would anyone think that this would be the way to win over the squishy centrists? A big part of it is motivated reasoning. The elite myth of “the pardon was good because it let us heal” (the Profiles in Courage Award! ) is also one that tacitly endorses the idea that accountability is divisive. Well, yes: it sets the just against the unjust! There’s more to the claim that we can’t have a politicized justice system, but nobody seriously believes this is the case for the Trump situation, because there would be nothing more politicized than to let someone who rampantly and wildly violated multiple federal laws go free just because he’s up in the polls. You can tell, again, that nobody seriously believes this because there’s never a sense that, say, the Hunter Biden investigations should be dismissed on the same grounds.

But another part of this is just to dangle the prospect of difficulties and uncomfortable situations. Most people are conflict-averse, and everyone’s a magical thinker sometimes. The promise of the Ford/Nixon analogy—which is bluntly wrong as a matter of historical fact, but which is being constructed as a political myth—is that if we do the convenient thing, all of these difficulties will … go away. It’s cheap talk, but, hey, sometimes working the refs works, and if you can keep a few more voters onsides by circulating this meme then it’s another way to mitigate the consequences of accountability.

It’s time to fully embrace the countermyth. Ford’s pardon of Nixon was what it seemed like: political expediency. (I don’t think there was a “corrupt bargain”, by the way, not least because Ford wasn’t Nixon’s first choice and because by July 1974 Nixon had very little leverage.) The aftermath of Watergate, like the aftermath of the Civil War, should be better remembered for the actions not taken that left the rot to fester. And we should insist on a system that really does work and one where plain violations of the law are punished within the law.

In a purely transient political sense, it was also totally unpopular and played at least some role in Ford's defeat in 1976 as well as hamstringing his shortened administration. (On the plus side, disgust with the pardon is what spurred a lot of good oversight legislation and a lot of turning over of rocks to look further at the crawling things hiding underneath.) But that's our Sanctimonious Political Class for you: always ready to endorse a catastrophically stupid own-goal political move that is also dubious ethically in deeper ways in order to pursue a vision of phony top-level consensus that is mostly about making sure they live in the most narrowly frictionless world possible for facilitating their own financial and institutional deal-making.